What a year for prose! As a poet myself, this might sound partly like a concession, but many of the prosaic tones, long lines or paragraphs that I’m thinking about were ones found within poets’ volumes. Prose, in 2013, seems to be the poetic instrument of not just our moment, but our time for its sly flatness, its passive mutability. Kenneth Goldsmith’s Seven American Disasters and Deaths stuck with me because I too am riveted to what Dorothea Lasky calls our very American obsession with “disaster porn.” But Goldsmith, who has been the lightning rod of much aesthetic division in the poetry world this year, has produced a book far less rigidly “conceptual,” I think, than it is pathetically documentarian. I found the transcriptions, from the radio broadcast following the JFK assassination punctuated by commercials to the Columbine High School 911 phone call while the shooting was in progress, neither Capote-journalese nor Mailer-operatic. A moving book with revealing afterward.

I come back to this word, “documentarian,” to explain a lot of what I think poets’ prose was up to this year—a dangerously catch-all word, I know. Ann Lauterbach’s newest collection, Under the Sign, reviewed in these pages, features a long, multi-section prose meditation, “Task,” that shows, with almost the illusion of a diarist’s casualness, how multiple in tone and genre a prose-block may be: musing on the changes of New York City, supple weather descriptions, the softer personality affects of Warhol, loaded etymologies, Emersonian trivia, sneaky theoretical conundrums and autobiographical fictionalizations. It’s a stupendous stretch of prose within an already distinguished collection. “Task” is beautifully close in spirit, though at a remove, to the rambling and existential consumer digressions in Dana Ward’s second book, The Crisis of Infinite Worlds, which I also read this year, resisting and wrestling with it yet succumbing ultimately to its tender, all-too-human navel-gazing—recalling Coleridge the intimist in his conversational poems as much as the sprawling antics of Ted Berrigan. How different in mood to Rachel Levitsky’s The Story of My Accident Is Ours, a gorgeous book that feels to me so personal precisely because of its ruthlessly anonymous, abstract, desperate thoughts, like the susurrus of some collective consciousness in heaven.

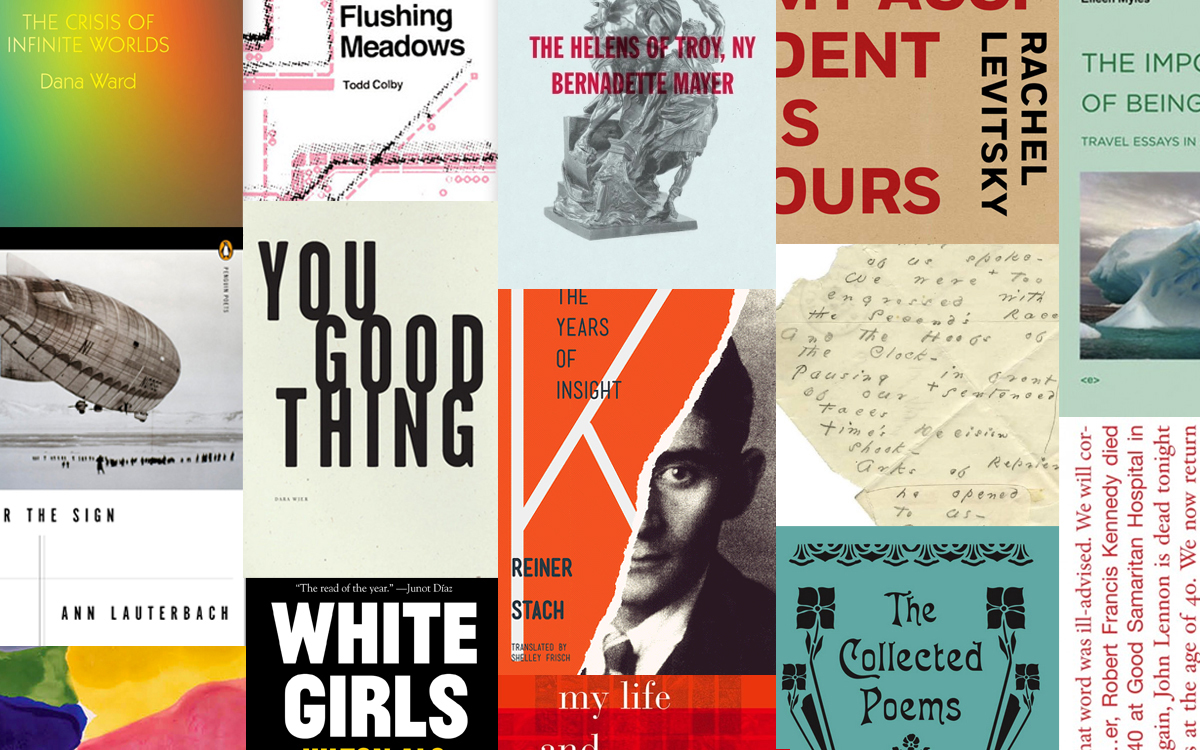

Lyn Hejinian’s My Life, flanked with its later installment, My Life in the Nineties, was republished this year by Wesleyan. And while documentarian gambits like the ones described above are there, Hejinian’s style is at once more traditionally poetic—a crammed, psychotropic buffet of rhetorical and literary devices—and more radically fragmented. Each sequence is like a standalone bead of impressions, memories, and syntactical ballet care of Gertrude Stein, less gnarled, more lyrical, yet happily just as disjunctive. Two of Stein’s other equally brilliant inheritors, Dara Wier and Bernadette Mayer, also released new volumes I loved this year: You Good Thing and The Helens of Troy, New York, respectively. Whereas Hejinian prefers her demolitions almost at the syllabic level, Wier plays within the very nature of stanzaic structure—accruing or disposing meaning across poems that are fourteen lines and yet wildly more than a ‘new collection of sonnets.’ Mayer’s unit is the book itself, its general conceit and transformative genre: transcripts of interviews the poet conducted with native Helens in Troy, New York become formal, haunted poems.

Another classic received its much needed exposure and return: Renata Adler’s Speedboat, a book I have no intention of reading straight-through but doubt I will ever stop rereading backwards and forwards as long as I have eyes. Adler, like no other prose writer I know, perfected the disorientation of absolutely conventional sentence structure with maximum dizziness in progression, in sequencing: clipped or wayward, all of the lines feel hard jabs, patron saint reliquaries of ADHD, frenzied, discontinuous. The scariness, of course, is not how foreign Speedboat feels, but how at home, as if it was written tomorrow. Yet even so tautly manic a surface-style can’t distract from the penetrating, fleeting treatment of Adler’s gaze, care of the narrator. On a single page, I count a dozen microscopic revelations of thinking, about Kipling, city sidewalks, the writing life, redwoods, Sensitivity Training and Paris in the last days of the Algerian crisis. Speedboat is not so much a pithy distillation of life’s random thoughts and sensation; rather, it plugs you into the very tachycardia of contemporary reality experienced simultaneously.

This year I finally caught up with some things I had been missing out on: Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, nearly all of Maggie Nelson, including her massive historical and analytical account of women painters and poets from the New York School. Eileen Myles’ The Importance of Being Iceland, which does prove her hand as one of the most riveting prose stylists of self-consciousness, of art writing and much else. Ditto Dennis Cooper’s Smothered in Hugs: Essays, Interviews, Feedback, Obituaries. How I enjoyed his interview with the boyish obliviousness of a young Leonardo DeCaprio, a reassessment of Quentin Tarantino’s overrated oeuvre, and a hard, bracing glance at William S. Burroughs’ surrender to celebrity. Like Kate Zambreno, and many others I know, this year I read Middlemarch—simply the most intelligent English novel ever written, sentence by sentence, tortured love drama by tortured love drama. I discovered the poetry of Todd Colby, care of John Ashbery, one of his most devoted readers. My recommendation: start with the pervy finesse of Tremble and Shine or Flushing Meadows. I read Monica McClure’s first chapbook, Mood Swing, and loved its play with an alienated/alienating female psychology, the trope of white girl privilege, the lackadaisical horrors of an internet existence merging with IRL.

I began 2013 swallowing a lot of hard drugs, also known as German idealism: Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Spirit, which I never finished, but found the famed Preface worth the thigh-burn for such crazy sublimity. Deleuze’s The Logic of Sense and Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, two books which I also didn’t finish—I confess to preferring Deleuze, like most theory, better in small bites. (Hence Agamben’s Profanations: slim, musical chapters dryly organized together, being easier to devour in toto this year.) Frederich Schlegel’s Philosophical Fragments, I being terribly fragmentary myself when it comes to reading, especially philosophy, struck me as the perfection of that form. I can’t retain the argument of philosophers, let alone their systems—but like the lame mercenary of the mind I am, I go to them for the crystallization of an abstract thinking that I both prize and will never have.

Rare finds: Guy Davenport’s Objects on a Table: Harmonious Disarray in Art and Literature. John Thomas Smith’s Nollekens and His Times, the nastiest, most disparaging biography I’ve ever skimmed through. Essay Collections: Wayne Koestenbaum’s My 1980s and Other Essays and Hilton Al’s White Girls—both having the queer, probing intelligence I so envy, each done in such varying temperatures: Koestenbaum, the smartypants sentence-pyrotechnic of panegyrics on Sontag, Barthes, and James Schuyler; Als, someone who astonishes for his restrained projections into the ambivalent crevices of invented identities: Michael Jackson, Truman Capote (whose presence is felt throughout), Flannery O’Connor, Eminem. Who would be more loudly hetero in comparison than Norman Mailer, whose thousand-page totemic official biography was just released (no thank you) as well as Mind of an Outlaw: Selected Essays, a book I’m quite thankful for. Mailer doesn’t resemble David Foster Wallace in the slightest—yet with both writers I have subzero interest in their fictions even while their forays into the essay seem to me compulsively gripping. Mailer, no formal innovator like Wallace, had in terms of subject matter far greater scope. His pieces really chart a thinking through—on race, hipster culture, homosexuality, psychoanalysis, the intellectual as public figure, fellow novelists new and old. Subjects even larger than his own ego torqued his thundering self-interest into something far more appealing to read than a writer’s perfunctory, liberal enlightenment: a terrible honesty about the complexities of American culture. In this respect, he has some of James Baldwin’s pointblank heroism, though Mailer’s sentences are nowhere near as arresting nor lovely. His integrity—irreverent, unapologetically reckless, biased—is maybe what recommends him most.

This year I read further in Judith Butler; read all of Rae Armantrout’s recent collections; enjoyed the art writings of Bruce Nauman and a Ryan Trecartin art monograph. I luxuriated in the craft of Alan Dugan’s Poems Seven: New and Complete Poetry; reread Beckett’s ingenuous essay on Proust (published as Proust and Three Dialogues). I’ve danced and dabbled in the Cornell-box inventions of Max Jacob. I’ve read, now, I think, every book of essays by William H. Gass, who I contend makes the best re-introducer to writers you already know and love, but could never consider so roundly, so singingly, written as his books are in the brassy, orotund rhetoric of Sir Thomas Browne and Samuel Johnson. Read his essays on Emerson, Stein, Nietzsche, Rilke. Then read all of them. Emily Dickinson’s The Gorgeous Nothings, her poem-fragments written on household envelopes, is the most beautiful book of the year, physically, and in every other respect. Library of America’s edition of Susan Sontag’s essays from the 1960s and 1970s, along with a few uncollected pieces reminds yet again just how indispensible she still is.

Books I dropped or turned from? Italo Calvino’s Letters didn’t catch me. Christopher Hitchens’ flabby book of middlebrow reviews and essays, Arguably, is, well, both flabby and middlebrow. Anne Carson’s Red Doc> left me missing The Autobiography of Red. Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge had little blood or edge to recommend it—while the contemporaneity dazzled (Britney Spears gets a shout out in the first ten pages), I found less narrative mojo pushing me forward than even his last, the pulpy stoner LA detective novel Inherent Vice. The Collected Poems of Marcel Proust assembles many of the finest translators to remind us of what Proust couldn’t do too compellingly in Alexandrine French verse, which was innovate and revolutionize language. Luckily, he could in titanic blocks of flowing prose. In Search of Lost Time turned 100 this year.

My favorite biography published? Without question Reiner Stach’s Kafka: The Years of Insight, the second volume, translated by Shelley Frisch. Insight is exactly what Stach provides, with such grace to his contextualization—the juxtaposition of man, writer and world feels less like an interpretive raid and intrusion on Franz’s neurotic yet highly-imaginative autonomy as artist than attentive credit to what materials his loopy mind transformed. (In one passage, K. visits a mock-up military trench installed in a city square to rally public support for the war effort; soon after he begins penning “The Burrow.”)

I’m eager to begin Renee Gladman’s Ravickian trilogy, the latest installment, Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge published recently. To sleuth after Lee Harvey Oswald in Don DeLillo’s Libra now that I’ve completed White Noise (a sustained miracle in sentence making, a great sitcom of postmodernity). To read everything that Kate Zambreno has ever published, and ever will. To finally finish Moby Dick (embarrassing, I know), to dip back into Andy Warhol’s The Philosophy of Andy Warhol for the limpidity of its benign charms. Must read more W.G. Sebald before Judgment Day. To see what 2014 brings (Peter Gizzi’s Selected Poems, for starters). That should be enough. More than enough.

✖