Here’s a painting, a dream: Woman Sewing by Lamplight painted sometime between 1870 and 1872 by Jean-Francois Millet. It depicts what its title names, a woman sewing by lamplight. She’s young, late teens or early twenties, her head bending towards her work. Behind her in the hazy glow farther from the lamp is a sleeping child, his face flushed and bruisy with illness. She sits close, not watching the child, but watching over his sleep. There is something of perfect calm in the girl’s face—she must be anxious for the child but what I see is accepting tenderness, a concentration over her work which is not complete absorption, but which diffuses like the light of the lamp from the bright point of her needle to fill the room with a kind of glow. I look at her clothes: white cap covering her hair, heavy red cloth around her shoulders and crossing at her chest, striped blanket over her lap. The fullness of her dark blue sleeve occupies the lower right of the painting until it fades into the shadows of the room. The room must be chilly but she seems at ease, not hunching or clenching.

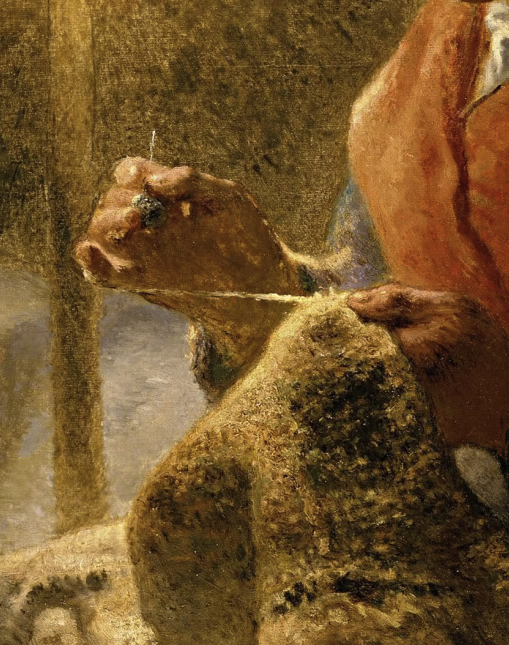

The lamplight of the title is given off the open flame of a small oil lamp fastened high on the child’s bedstead. The effects of the painting are of light and glaze and shimmer. In her lap, on top of the blanket, is the piece she is working on, to my eye a heavily knit sweater or blanket cascading in thick variegated folds in shades of brown, black, darkened ochre. She holds a thick needle upright, glinting in the light, and from it comes one bright translucent thread of yarn stretched taut.

So here we are, not citizens of Millet’s time, which was the fading quarter of the 19th century. We never see women sewing in their homes by open flame into the night. The idea is so far from us in the history of ordinary experience that it is not even nostalgic. Millet’s virtuosity with paint and depiction is apparent, even without connoisseurship—there is a strange shimmering quality to the painting, a buildup of translucent veils of color that make the light seem a thick liquid, like honey. But is virtuosity enough to surprise us? We live in an age of dazzling optical light effects produced by casual electricities, by cheap gadgets, by innumerable screen simulations in the most ordinary ad, TV show, video game. Even our phones shine and seduce. And of course we see pictures of faces and faraway scenes everywhere we look. An age of miracles.

To have an encounter with a painting like this you can’t just stroll by. Glancing here, glancing there, waiting for your gaze to be captivated, you will almost certainly walk past the painting, barely pausing, letting only the faintest impression linger.

To see a painting like this it is necessary to stop. There are a hundred great paintings in the surrounding rooms, but for a time, at least, their calls for attention must be resisted. There is an effort at this moment. An effort to bring yourself to the work.

What will you see if you look longer, look harder? Of course I don’t know. At the moment anyone begins to see a painting, they begin to make it. Even the facts of the painting will shape themselves to your seeing. A friend who looked at this painting saw a wagon wheel in the shadows. Another saw a spinning wheel. I saw no such thing. Is the girl old enough to be the mother of the child? Is she a sister? An indifferent house maid? Is she content, tender, anxious, sorrowful? Is she attentive to the child or so absorbed in her work that she neglects him? Is the child boy or girl, sick or sleeping peacefully?

And I don’t know if your feet might be hurting, if the room is crowded or spare, if you’re preoccupied by a phone conversation you had earlier, if you’re feeling lonely, or anxious, or thrilled. I don’t know if you’ve studied paintings like these, or always avoided them, if you like domestic life in general or if you fear it.

One familiar way to spend your time in front of a painting like this might be to listen to the audio guide, read the wall label, try to learn about the circumstances in which it was painted, place the artist historically, guess at his concerns, what he might have been trying to convey. In doing this, you place yourself in the hands of experts and connoisseurs, those who know much more than you, or appear to. But none of them are standing there, and most importantly, none of them are you.

In truth, the painting can do nothing, mean nothing, without you. It needs more of you than the scraps of fact you can glean by leaning into the little paragraph mounted on the wall.

The painter may be a great one, and the painting a masterwork, but they are as nothing without you. You, as you are, sore feet, scattered mind, unable to remember from some art history class years ago just why Millet was supposed to be important. Didn’t Van Gogh maybe like him? Were there haystacks? You, a little impressed by the paint handling but not stopped in your tracks, ready to walk on into the next room, and the next, until it’s time for a cup of coffee.

The painting, in this moment, needs you, exactly you. Nothing less.

Greater expertise might make you more confident, but it does nothing, by itself, to bring the painting to life—if anything, experts tend to categorize efficiently and move on: “Ah, yes, one of Millet’s domestic scenes, a fair example though not his best.” From the painting’s point of view this kind of diagnosis is no better than a dismissal.

So, how to begin? From this unpromising beginning, what?

Arguably, the simplest and most important gift you can give the painting is time. Just that. Stay.

So, standing there, what do we do? Here’s what happened between that painting and me, unlikely pairing, unpromising match that we were. My friend Jac had suggested something: that I come to the painting as if it was my own dream. If I had dreamed her, what did it say about what I desired? Desire is a twisty thing in dreaming, appearing disguised and inverted, mirrored, metaphored. But that day I wasn’t feeling twisty—symbols and reversals didn’t occur to me. Instead, I was having, on the simplest level, a bad day, with waves of uncharacteristic resentment at the smallest obstacles.

So, in that moment, I took his instruction rather differently than I might otherwise: dream as wish, as undisguised desire. I looked at the painting, and because it was a dream, stopped seeing it as painting. It wasn’t a made thing; it had no maker. The idea that I was dreaming let me fall in, forgetting the room, the frame, the wall, the sounds of the people around me. The stillness and quiet of the painting came out to encompass me. I let my gaze roam the lit surfaces, the bright lamp, the bedpost, the cap covering her hair, the fabric at her shoulders, the child’s round cheeks and white sheets, but most of all her face held in profile, mostly in shadow but marked with a glowing line that traveled brow to nose, picking out her upper lip and chin. I watched the expression on her face, and found that yes, I did desire this. The clarity of her task: the boy was sick, someone had to sit up with him, the sweater had torn or unraveled, it needed mending. The girl’s life at that moment seemed comprised of necessities rather than choices and her demeanor seemed to express a sense of repose in those necessities. I saw tenderness there in her complete absorption with her work. I saw acceptance. I saw a moment when it seemed that intention, action, need, and feeling all clarified into one gesture. She held the needle high, thread taut. I could imagine the stars unseen overhead, wheeling slowly around that stillness, that still point. I could imagine myself, from where I really was in space and time, held equally in the clarity of that long moment. My own desire settled, aligning to match my action and circumstance.

I stepped away for a little while, breaking the dream, looking around the room I was really in, listening to voices and conversations, seeing feet and coats and faces. When I came back to the painting, I flipped the game: I wasn’t dreaming her, now she was dreaming me. What a crazy, improbable dream.

Her dream: She is standing in an elegant red-walled room where paintings are hung in spacious order. She has just come in from the street, and she wishes she could go back out, to pause in a crowded intersection and stare up at the sky. All the life around her, all the variousness, a whole city spreading in every direction, hurrying with innumerable purposes. In such a city, you could do anything, be anything, be always becoming.

She is dreaming that she is me, remember, so she is dreaming not so much her own naive startlement (as I might imagine it) but rather a full dose of what, on this particular day, is a hot mass of dissatisfaction, an unusual spike of crankiness. And I ask myself, as I try to do this flipping of perspectives, how could she possibly be wanting this? Could she desire resentment, confusion, moments of urban rage, a critical eye cast over the display of wealth and power the room represents?

Suddenly I feel I know just what she wants. She wants to stand up from the chair in which she had been sitting so quietly, to step up and away from all that certainty. She wants to be in a city, free to leave, to walk outside, to turn her face to the sky, to wear jeans, to be with friends talking and drinking coffee or a glass of wine, to be able to alter the trajectory of her life, go to India with no phone, climb the Himalayas, move to a small town in Alaska and start over, work in a diner off the highway. She wants to be too hot instead of chilled, she wants to be resentful instead of accepting, she wants not to love, she wants to be able to turn away, put down caring like you could put down your sewing, she wants to doubt, to be angry, free.

And in that moment the sense I have of my own life shifts. A strange sense of doubling, of being separated from my life, which I had been aware of all day, falls away. Frustration itself becomes something worthwhile, connected to life. All the bad feelings inhabiting me, by becoming something I imagine she would choose, and choose gladly, also become something I choose gladly.

Obviously, this set of imaginary gymnastics has as much to do with me as with the painting. I bring my own life to it, the city I live in, the historical time I inhabit, my moods, dispositions, preoccupations, my way of perceiving the space in which the painting is hung, the body sensation of being overheated, my social world, scattered bits of knowledge about art history, filmy layers of past experience looking at and making art, everything.

But it’s not as if the painting itself isn’t there. I do my best to perceive it, to observe and notice its attributes, to register its temper. I give it a long look (very long by museum-going standards). How much does it matter—or in what way does it matter—that I don’t know much about Millet? Even what little I do know, I’ve largely put aside in this mutual dreaming. The painting and I have had an encounter, we have meant something to one another. Whatever the intentions or desires of the artist, I have no way of knowing if anything I experienced or imagined aligned with them. I had an encounter with myself as much as anything. And yet there were aspects of the experience that could have never occurred without the specific physicality of the painting.

What would it be like to keep going? What would it mean to put aside for a time the canons of art criticism and art history, to forget omniscience, judgment and being right, and instead look at art idiosyncratically and personally, as if it were part of lived experience, part of the dream of the self?