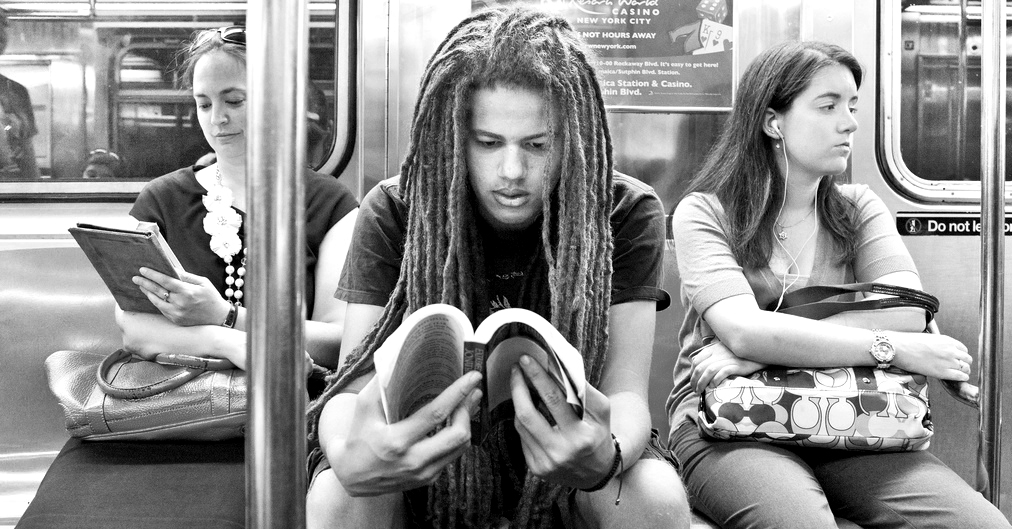

New York City’s subway system is (for the most part) one of the last places that remains beyond the reach of Internet and smartphone. When bored and riding the train, I turn to a book to fill the time it takes to reach my stop, and I’m not alone in doing so. In the Underground New York Public Library photography Tumblr, Ourit Ben-Haim has quietly assembled a powerful portrait of the collective reading habits of New York City commuters. The photos collected on the site present a literary take on street photography, each image capturing a spontaneous moment of connection between reader and book.

Every scene on Ben-Haim’s site is as personal as it is fleeting, and unmistakably urban in composition as well as setting. Ben-Haim frames her subjects between metal subway poles and train car doors. Sometimes, she spots and snaps readers standing on opposite subway platforms through her train’s windows. The titles represented on the site are as diverse as the faces of the commuters themselves. One photograph: two young Orthodox Jews hunch into open copies of the Talmud. Another: a seated man props his chin on one hand and with the other holds open the pages of American Psycho. Yet another: a woman walks forward blindly, her head buried in a copy of Madame Bovary.

Ben-Haim doesn’t interview her subjects, and her photographs rarely include identifying details about the subway stations and train lines that form the settings for these tableaus. These men, women, and children are tabulae rasae. Free of context, we can simply appreciate the books they hold and their total absorption in the stories in their hands. We glimpse into their personal escapisms, take note of the adventures and worlds they choose to immerse themselves within, and are reminded of our own memories of reading beloved titles, on the subway and elsewhere. We feel close to these anonymous readers. We share their love of reading, and of story.

Yet we know that photography is hardly as objective a medium as it appears at first glance. In our Internet-fueled culture of incessant self-scrutiny, it is a matter of course to contort ourselves into unrecognizable semblances of ourselves, always designed with an audience in mind. (Lauren Bans recently skewered this practice in her GQ piece “Stop Showing Me Your Internet Face.”) Self-depiction must inevitably yield artificial facades, the constructed “better” versions of ourselves we believe we should be.

Perhaps then, one might argue, it is the task of street photographers like Ben-Haim to present us as we really are. But is street photography actually more capable of capturing a genuine portrait than a posed photograph?

Walker Evans, a champion of photography as a means of “pure recording,” believed it was. In fact, eighty years before Ben-Haim began UNYPL, Walker, too, hit the subways in search of opportunities for authentic portraits. His 1930s series of subway portraits gives us anonymous riders in close-up, captured on film by a camera concealed inside his jacket. “The guard is down and the mask is off,” Evans wrote of this series. “Even more than when in lone bedrooms (where there are mirrors), people’s faces are in naked repose down in the subway.” These faces are genuinely expressive because the subjects don’t identify the camera in their midst. They are free to look exhausted, dejected, reflective, distracted; the full range of human emotions plays across their faces. They are uninhibited and exposed.

The UNYPL project hinges on the intimate connection between anonymous reader and unnoticed observer. And this unnoticed quality is as key for Ben-Haim as it was for Evans. If the photographs on the UNYPL site took a turn toward the pseudointellectual, if these subjects choose to read À la recherche du temps perdu, or Moby-Dick, because they realize Ben-Haim is watching, then the project’s chief charm would be spoiled. This secret glimpse of commuting strangers, however, is not only the project’s main appeal, but also the source of its moral grey zone. Unsurprisingly, “Is it wrong to take photographs of people without their permission?” is number two on her Common Questions page, and Ben-Haim’s considered response is worth a read.

Is it possible for an uninfluenced emotion to be captured in any photograph, whether the subject is aware of the photographer or not? What are the ethics of an unannounced photographic capture? Ben-Haim, along with many other street photographers, has begun to wrestle with these questions, and will certainly continue doing so.

Until then, we can appreciate Ben-Haim’s efforts. Her UNYPL is unquestionably a beautiful assemblage of captivating photographs: a collection of small instances of the great pleasure that we commuters feel when freed, amid a crowd of strangers, to delve into the book that will get us from one place to another.