This story has been drawn from Vol 1. No. 5/6 of the American Reader (now sold out). To subscribe to the American Reader, visit our Shoppe.

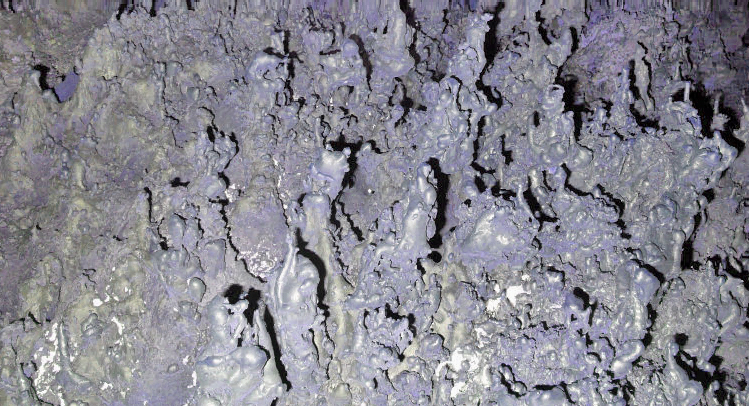

The stuff was thick. It was denser today, and so when Trimble dropped his key card outside his office door, it was not swallowed up like so many before it. Instead it rested on the surface, with its magnetic strip down. A single corner was taking on the gunk.

He picked up the card and wiped it clean on one pant leg, leaving behind a trail that would later crystallize in the fabric. Trimble cursed himself. The card required several swipes due to the buildup in the pass box—its narrow slot expelling a single, mucoid tear. Finally it clicked and he put his shoulder to the door. Its rubber sweep pushed a wedge of floor momentarily clear, before the stuff reclaimed its level, chasing the door back on its own time. The stuff was oblivious.

He lifted the cellophane sheets from the desktop, and from his high-backed chair and the two chairs opposite, folding them in by the corners so they sagged with its weight. From inside the top drawer he removed several large ziplocked bags, their folds already firm from last night’s gain. The first bag contained his personal effects: a prescription container, and a drinking glass, and the framed photographs of his first and second wives. From the second and third bags Trimble removed his stamps and pads and inks—black and blue and orange—and his nameplate, and the pens and pencils and digital recorder.

His phone rang and he unsheathed it. It showed Lynn, upstairs, her blurry face.

“Good morning, Mr. Trimble.”

“Lynn.”

“What a morning…”

“Yes, the shit is thick today.”

“Tell me about it,” she said. “You could almost walk on top of it.”

Trimble didn’t like to wear the waders in his office. He drew them down by their elastics, at his knees, before knotting them inside-out and tossing them into the wastebasket. He removed his shoes and socks, too, stuffing them into the ziplocks and cuffing each pant leg high on the calf. Then he let his bare feet go down into it, between his toes and up above the ankles. As ever, there was something just short of comfortable about it. It was never quite warm, or cool, enough.

“Christ…what’s on the docket.”

“A young couple, Haviland. Nine o’clock.”

“And that would be…now?”

“Now, Mr. Trimble.”

“This shit is disgusting…and I have this file? Havelman?”

“Haviland. It’s in the dessicator. And for lunch?”

“Whatever you guys are doing.” He pulled on a single latex glove and reached for the quietly humming appliance next to his desk. Making a spatula of three fingers, he worked them around the lid on top, heaving it in gobs onto the floor. With his dry hand he punched in the code. The top popped, and the acrid preservatives wafted out.

“And Lynn,” he said, removing the file in question, “this is cleared already? Because I don’t see a psych stamp.”

“Psych is pending.”

“Psych is pending,” he sang back.

Trimble remained seated as the door clicked and slowly plowed away a new arc. The couple pushing into its wake did not appear to be young at all. They were dressed in loose-fitting earth tones—curtains of coarse fabric draped over their shoulders and bony hips. Hanging from the man’s shoulder by a worn strap was a leather cylinder the length of his own arm.

“Good morning,” said Trimble.

“Good morning,” they said. She made no eye contact.

“Please,” he said, indicating the two chairs opposite. As they neared he saw that their baggy pants were banded with reflective grit, beginning just above their boots and moving up onto their thighs. He read these jeweled hoops like rings in a tree: middle class, state school, lowlands….

“Stuff is pretty high out there today,” said the man.

“Yes,” said Trimble. “But it’s not the depth…”

He left the man an opportunity to finish it. But the man’s thin smile was already gone, and he now wore the same lipless face as the woman. She looked away, staring at the wall with the framed degrees.

“…it’s the viscosity,” Trimble said. “In any case I don’t think there’s much to cover here.” He looked the file over as he spoke. “And you still reside down in Hurling…?”

“In the Damps,” said the man, his fingers curling tightly around the cylinder in his lap.

“In the Damps.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And that’s…drywall construction?”

“Drywall.”

“And you’ve been approved for renovation?”

“They gutted about three feet,” the man answered. “Threw some stones in.”

“Sorry, no, I was referring to comprehensive: new footings, poured floors, aeration.”

“Nope.”

“I see,” said Trimble, scribbling in the margins. “Well, that can be arranged once this goes through…and do you have access to temporary housing?”

The woman’s chest heaved and her potato-sack blouse billowed in turn. Trimble saw the black vine tattooed around her neck, and just next to it the poorly rendered head of a toddler, its cranium distorted by her jutting clavicle. On her sternum he glimpsed the little hyphen and its bracketing dates. But the font was too decorative, and the ink had bled, and he could only guess how long ago or far apart the years were.

“We’re staying at her mother’s place,” said the man, indicating the woman with his thumb.

“Also in Hurling?”

“Ledderton.”

“Ledderton.” Trimble wrote it fast, in his worst hand. None of the rest was necessary. Besides, it was all funny money by now. They just keep on printing more of it, and there was no good reason these sad sacks from Hurling or wherever shouldn’t get some. He inked up the stamp with the hawk-and-star and pressed it onto multiple forms.

Someone lifted a foot, producing a wet suction.

“Excuse me,” said the man.

“You can set up direct deposit for this,” said Trimble. He placed the couple’s copies inside a plastic envelope and handed it across the desk.

The man’s fingernails were sugary with particulars. He removed the documents from the folder and curled them into a tube, which he then slid inside his cylinder. The woman looked at Trimble for the first time. He had been waiting for her to make eye contact, but now he couldn’t bear it. Her eyes were like mineshafts and he had to look away. The man mumbled thanks. They stood and made their way to the door like yaks in the tundra, heads down and in single file, her steps falling into each of his fresh impressions.

Trimble watched the surface recover its reflective glaze, watched their footprints vanish in the order they were made. In the very middle of the floor, a mess of lights and polished brass reformed into the shape of the chandelier.

The street-side window was fogging at the edges. It showed the gray hindquarters of their state-issued hack, which was tethered—he guessed—to the fire plug. Its legs were encased in fused geodes, save at the knees, where the cycle of coating and shattering resulted in raw, hairless patches, scab-flecked and pustulant. A horse is a rotten thing. He watched its dreadlocked tail jerk as the woman mounted. Only her rounded back was visible, the slack burlap of her shirt held fast by the cylinder’s strap.

Trimble studied the photograph on his desk, the older of the two.

The two of them were seated together in a field, somewhere out west. She cradled his head in the folds of her summer dress, her chin inclined and eyes closed, drinking in the low sun. He wondered who had taken the picture. Had they been traveling with a friend? In Lawrence maybe? He couldn’t place it. In order to find out he would have to take a picture of this picture, and send it around to all the people they had known, asking if they had taken it, and if so where, and when.…Trimble closed his eyes against a budding headache.

Some time later he was startled by his phone.

It was the tinny news loop—the markets and scores and show times, and the gain, the viscosity. His mouth tasted like rubber. On the desktop his forearms slid out in the new glisten. Already? He raised his fingers to his chin, where it was webbed in the stubble. What had happened to lunch? It was dark out. He checked his phone and counted Lynn’s attempts to reach him, at noon, and 2:30 and 4:30. Outside his windows the street-side fluorescents were warming up, their aluminum husks already filmy with the dusk coat.

Looking down, he saw the couple’s paperwork. He’d only made it as far as their names, and Hurling, and the disbursement schedule—and now the sheet was pasted in place, the ink blurry where his forehead had been. He peeled it carefully from the desktop and opened the dessicator, placing it gently across the top. The pictures and the stamps and the nameplate and the digital recorder: everything was veneered in it.

Approaching the metered parking space, Trimble saw another laminated ticket in his windshield, pinned beneath the wiper. He added it to the pile in the passenger seat. The car started right up and he pulled into the glutinous street. But his plow wouldn’t drop. Again. He stopped and turned on the hazards, took the pick from the center console and squatted at the plow, hacking away at the gemlike barnacles cocooning its gears. Then he got back in and tried again, but no plow, and more chipping, and no plow.

Trimble called roadside assistance and a tow truck came. Its driver was a doughy kid in a plastic jumper and a miner’s helmet.

“I dunno,” the kid said, bobbing his light around the lifting mechanism beneath the plow. “I don’t think it’s the crust that did it.…”

He uncoiled a long hose from the flatbed, screwing one end onto a boxy tank retrofitted to the truck.

“What’s that?” said Trimble.

“Basically just vinegar. White wine vinegar.”

The kid squatted down at the wheel well, opening the door on a little panel next to the plow gears. Now Trimble could step in closer and see the young man’s frosted eyelashes, the quartz-like folds in his neck. The occlusion inside the panel was nearly opaque. The two of them watched as it slowly went bulbous and began its descent, pausing to flatten at the panel’s lip before crawling out like a slug. The young man used his fingers to work the remaining curd free. Then he lifted the hose and began dispensing its conical mist.

“I tell you what,” he said, “shit is thick today.”

“Tell me about it,” said Trimble. “You can almost…”

Can almost what? He trailed off, biting his tongue for want of something different to say. He pitied the young mechanic, pitied his jeweled neck fat and jerry-built vinegar hose, and he wanted to flatter him with something different. But there was nothing different to say, and this of course was the most horrible thing about it. You could try to diminish it by having new things to say about it, or by reducing it to a metaphor, by comparing it to other things. People tried it all the time. But the matter won’t have it. The only sane way is by squeegee—by squeegee and wader, and snot rag, and dessicator. The stuff doesn’t get anything else, and it sure as hell can’t tell a notary public from some glue monkey with a spray hose, or from a couple of Hurlings, or Leddertons, or whatever they were. And the ones who forget this—who keep trying to think it away—they’re the ones who get tired out and fall asleep in it, accidentally or on purpose.

The kid went on spraying.

Often on purpose, yes. In her case, however, it was certainly accidental. He’d been assured as much, not just by the county—by the coroner—but by his own mother-in-law. And who would know better? Then it came rushing up at him, all at once: the sunny fields and the truffle oil, the blistered feet. It was France, the South of France. Beynac. Is that a place? Bergerac. And not a friend at all, in fact, but the cottage owner, having found their camera in the kitchen—

“Nope,” said the jumpsuit, from behind the wheel of his car. “That’s not gonna do it either.”

Trimble was still catching up, still reaching: “…but I think I saw that it’s supposed to loosen up over the weekend.”

The plow never dropped.

He left the car there, on two wheels, as it was being pulled onto the truck’s flatbed. He was struck by how short a distance he’d trudged before the sound of the tow chains was smothered by the young night, by the new effusion. Lights appeared here and there in the balconied apartments above, putting a faint glow into the fire-escape formations—the stalactites and stunted chutes. Turning back, he saw his tracks dissolving in the pearlescent street. He crossed the fleeting wake of a silently passing livery car. A large herding dog waited in sentry outside a bodega. Its white shag had long ago calcified into marbled plates, shifting hard at its begging joints.

Trimble was given a deaf start by a pair of Dominican teens.

They nearly clipped him in passing—a shirtless boy with a wispy moustache, fast on the heels of a small-breasted girl, her mouth open in terror. They chased past him into a dimly lit alley. Upon reaching that point he slowed, then froze. He saw them up against the bricks, the boy burrowing into her, his jeans down around his ankles, his belt capsizing in the gain. She was screaming, it seemed to Trimble, but he couldn’t hear her. He gripped the dowel on his squeegee, brandishing it, shaping it into a threat—until he saw that she wasn’t screaming at all, but laughing, and at the sight of him they fumbled into form, running into the night and leaving no traces.