When I wrote the essay “The Curses, the Fates, the Races, the Fakes, the Faces, the Names of The Game of Death; or, The Game of Death,” I only meant to illustrate a common point about how Asian men are denied a perception of full humanity; to that end, I deliberately misread Bruce Lee’s posthumous film The Game of Death as an allegory of Asian male self-regard, pointing out the various ways Lee’s face and image are appropriated. I wrote: “I may be criticized for obtuse misreading. But misreading is a fine way to approach miswriting, and to being misread.”

But what I didn’t expect was that the essay itself would eventually be misread, and that I would do the misreading. I find that whenever I look at my writing after entombing it in publication, look at it after I know that other people have seen it, the writing always seems to express something other than I intended, as if it’s been possessed, rewritten by a doppelganger. And now, as if I had no choice, I’ve returned. ((Despoiler Alert: The characters and incidents portrayed herein are fictitious, and any similarity to the name, character, or history of any persons is entirely coincidental and unintentional; death, eternal punishment, for anyone who opens this casket.))

The Pyramid Scheme

For the ‘double’ was originally an insurance against the destruction of the ego, an ‘energetic denial of the power of death’, as Rank says; and probably the ‘immortal’ soul was the first ‘double’ of the body. This invention of doubling as a preservation… led the Ancient Egyptians to develop the art of making images of the dead in lasting materials… But when this stage [of primary narcissism] has been surmounted, the ‘double’ reverses its aspect. From having been an assurance of immortality, it becomes the uncanny harbinger of death. —Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny”

That is why it is possible to view all films—but especially old films—as mummy films. Photography began, after all, as a mummifying technology, a 19th-century advance in mankind’s age-old mummy complex. With each passing era, I know, mankind has perfected the perverse art of preserving corpses. First the mummy, then the death mask, then the photograph. After the photograph, there remained only one logical step: the moving image. From Egypt down to the Egyptian Theater, there has been a direct and unbroken lineage. Every movie is a pyramid, stuffed tight with mummies. Every movie is a mobile gallery of death masks. —Bennett Sims, “White Dialogues”

I spent most of my previous essay pointing out uncanny coincidences in The Game of Death. Since it was mostly shot after Bruce Lee’s death, Lee’s character Billy Lo is played by body doubles, and has his face concealed or disguised for almost the whole film. The resulting movie is full of masks, doubles, resurrections, and supernatural occurrences—all of which fit strangely well with Freud’s concept of the Uncanny.

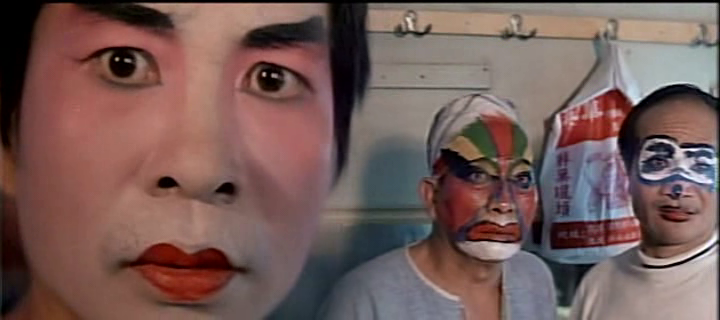

But I realized after returning to my essay that those uncanninesses aren’t just restricted to the character Billy Lo. I didn’t think much of the fact that the villain Dr. Land coincidentally fakes his death the same way that Billy Lo does—by creating a fake mannequin head—but now I notice that other characters conceal their faces as well: paraders in dragon costumes, and goons in motorcycle helmets, who ludicrously scramble into a dressing room full of Chinese opera performers, flooding the room with masks.

The coincidences aren’t even confined to the film itself—it spawned a number of fakes and offshoots, as well as an official sequel, Game of Death 2: Tower of Death. The sequel’s plot is entirely unrelated to the first film, but parallels abound. The protagonist of the film’s first half is still named Billy Lo ((Though at one point the movie forgets this fact, referring to Billy as “Bruce Lee”!)), but resembles the original Billy Lo only in that his face is concealed throughout. Billy is killed halfway through the movie (he falls off a helicopter), and is avenged by a double, his twin brother Bobby—both are played by Bruce Lee’s The Game of Death body double Tai Chung Kim. As in The Game of Death, there is a film within a film, masked assailants in a dressing room, a scarred face, a fake death, and a desecrated coffin containing a fake body. Most interestingly of all, Bruce Lee’s funeral footage is recycled ((The fake funeral sequence from The Game of Death used the actual footage from Bruce Lee’s funeral.)) once again—but this time, it’s used to represent Billy Lo’s actual funeral. So Bruce Lee’s real funeral, Billy Lo’s fake funeral, and Billy Lo’s real funeral are identical.

When Lee gained his stardom, other movie studios were eager to cash in by casting their own shades of Bruce Lee, enough to comprise a whole subgenre—the Wikipedia page for Bruceploitation lists Bruce Li, Bronson Lee, Bruce Chen, Bruce Lai, Bruce Le, Bruce Lei, Bruce Lie, Bruce Liang, Bruce Ly, Bruce Thai, Bruce K.A. Lea, Brute Lee, Myron Bruce Lee, Lee Bruce, and Dragon Lee. The 1976 schlocker Bruce Lee Fights Back from the Grave features zero footage of Bruce Lee and zero fighting back from the grave; in The Dragon Lives Again (1976), a faux Bruce Lee fights Popeye and James Bond. And Bruce Lee continues to be resuscitated by increasingly sophisticated means: to promote a Bruce-Lee-branded Nokia phone, a Chinese ad agency released a convincingly dithered viral clip that showed a Lee lookalike, wearing the tracksuit from The Game of Death, using nunchucks to play ping-pong. ((Both the phone and award-winning ad campaign were released in 2008 to commemorate Bruce Lee’s 30th anniversary. But Bruce Lee died in 1973; the 30th anniversary they must have meant was the 1978 release of The Game of Death, the anniversary of his resurrection.))

Even beyond its own direct sequels, spinoffs, and spoofs, The Game of Death finds systems of coincidences—especially with The Crow (1993), a godawful gothic blockbuster starring Bruce Lee’s only son, Brandon Lee. Brandon plays a murdered celebrity (“Eric Draven,” ugh) who, supernaturally resurrected, disguises his face and wreaks vengeance on the gang that killed him and his girlfriend. He boasts regenerative superpowers: no matter how many times he’s shot, he revives.

Among Bruce Lee fans, The Crow is most notorious for a coincidence that has inspired Lincoln/Kennedy depths of conspiracy-mongering. In The Game of Death, Billy Lo is shot by an assassin while filming a movie scene in which he’s shot and killed. And Brandon Lee was also shot and killed while shooting the scene where Eric Draven is shot and killed, with the cameras rolling the whole time. Some of the rumors accounting for this coincidence postulate that the Chinese Triad orchestrated Bruce and Brandon Lee’s deaths, others theorize family curses and fourth-dimensional beings.

That’s all fine—clearly I relish crackpot theories—but I’m more interested in the coincidences that seem to relate to Billy Lo’s identity crisis.

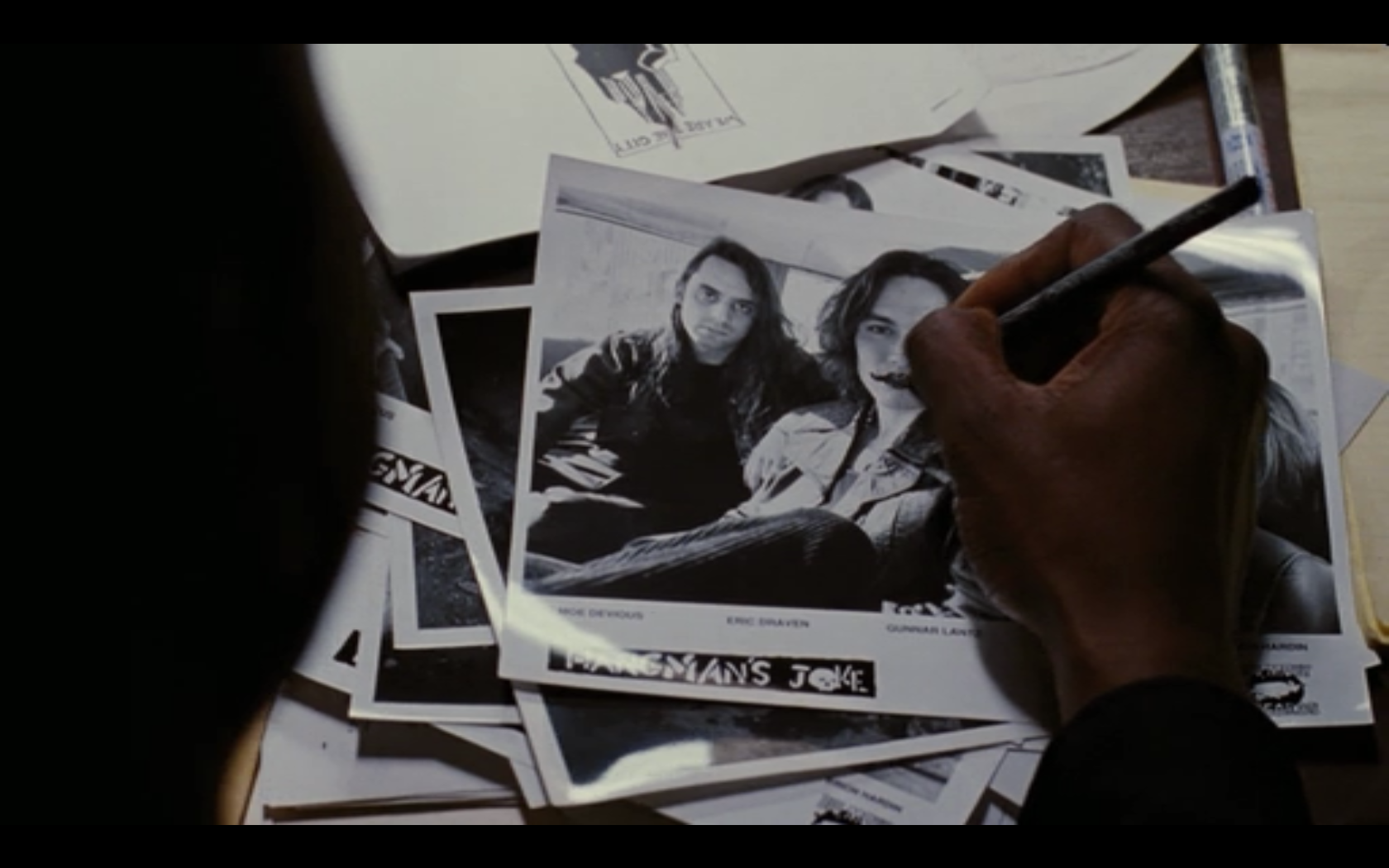

Like the scene where Eric, remembering a time he playfully wore a scarred harlequin mask, shatters a mirror and paints his face to resemble the mask (“Nice outfit; not sure about the face, though,” the villain Top Dollar taunts). Or when a police officer scribbles over a black-and-white picture of Brandon Lee’s mouth and eyes, like Billy Lo did with his own headshot. Set on Devil’s Night, the film is full of disguises and gloomy occultists (e.g. Myca, Top Dollar’s vampy Asian consort). And the scene in which Eric Draven is shot uses footage from the take in which Brandon Lee was shot.

Like the scene where Eric, remembering a time he playfully wore a scarred harlequin mask, shatters a mirror and paints his face to resemble the mask (“Nice outfit; not sure about the face, though,” the villain Top Dollar taunts). Or when a police officer scribbles over a black-and-white picture of Brandon Lee’s mouth and eyes, like Billy Lo did with his own headshot. Set on Devil’s Night, the film is full of disguises and gloomy occultists (e.g. Myca, Top Dollar’s vampy Asian consort). And the scene in which Eric Draven is shot uses footage from the take in which Brandon Lee was shot.

We also find that, as with The Game of Death, the film’s coincidences obtrude into reality. Interrupted by the accident in its final days of filming, it was completed with body doubles; the shot where Eric is falling to his death digitally superimposes Brandon’s face onto the double’s, a high-tech version of the infamous shot in The Game of Death where a cutout of Bruce Lee’s face conceals Billy Lo’s face. And Brandon Lee, like Eric Draven, was engaged at the time of his death; he was buried in his wedding tuxedo, and his fiancée wore her wedding dress to the funeral, the same way Eric Draven’s dead fiancée appears to him as he dies again at the end of the film.

The Crow was also revived in a series of decreasingly tolerable sequels—but instead of suffering through those, now I’m wondering if other movies exhibit The Game of Death’s strange coincidences. Perhaps the “curse” passed from The Game of Death to The Crow is not merely hereditary, but somehow aesthetic, or narrative, or transmitted by contact with Bruce Lee (Brandon Lee was his son, after all—Bruce Lee’s biological sequel). There must be other films that evoke The Game of Death’s uncanny themes and symbols; could they be somehow connected? Does The Game of Death breach not only the fourth wall, but also other films’ fourth walls?

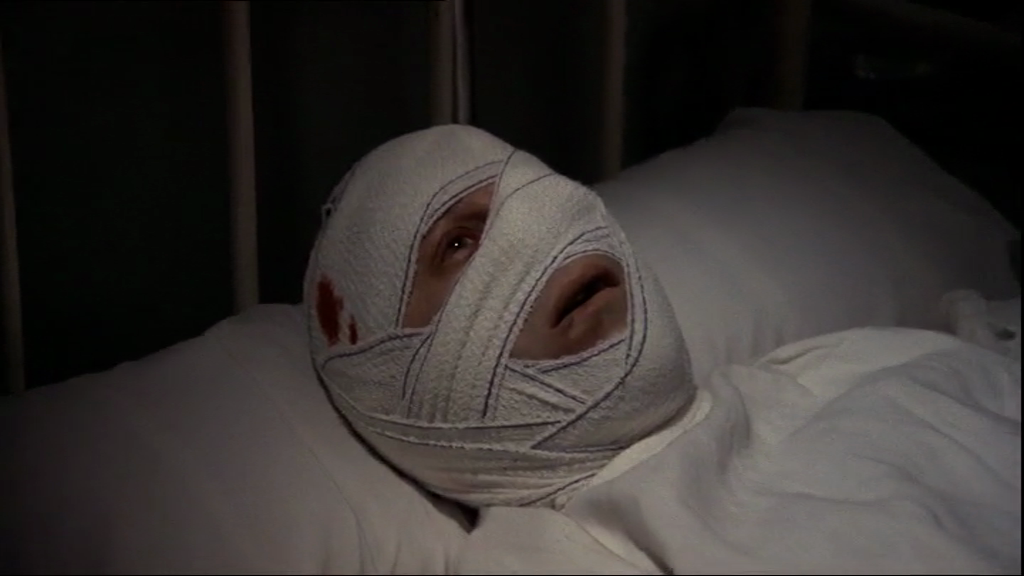

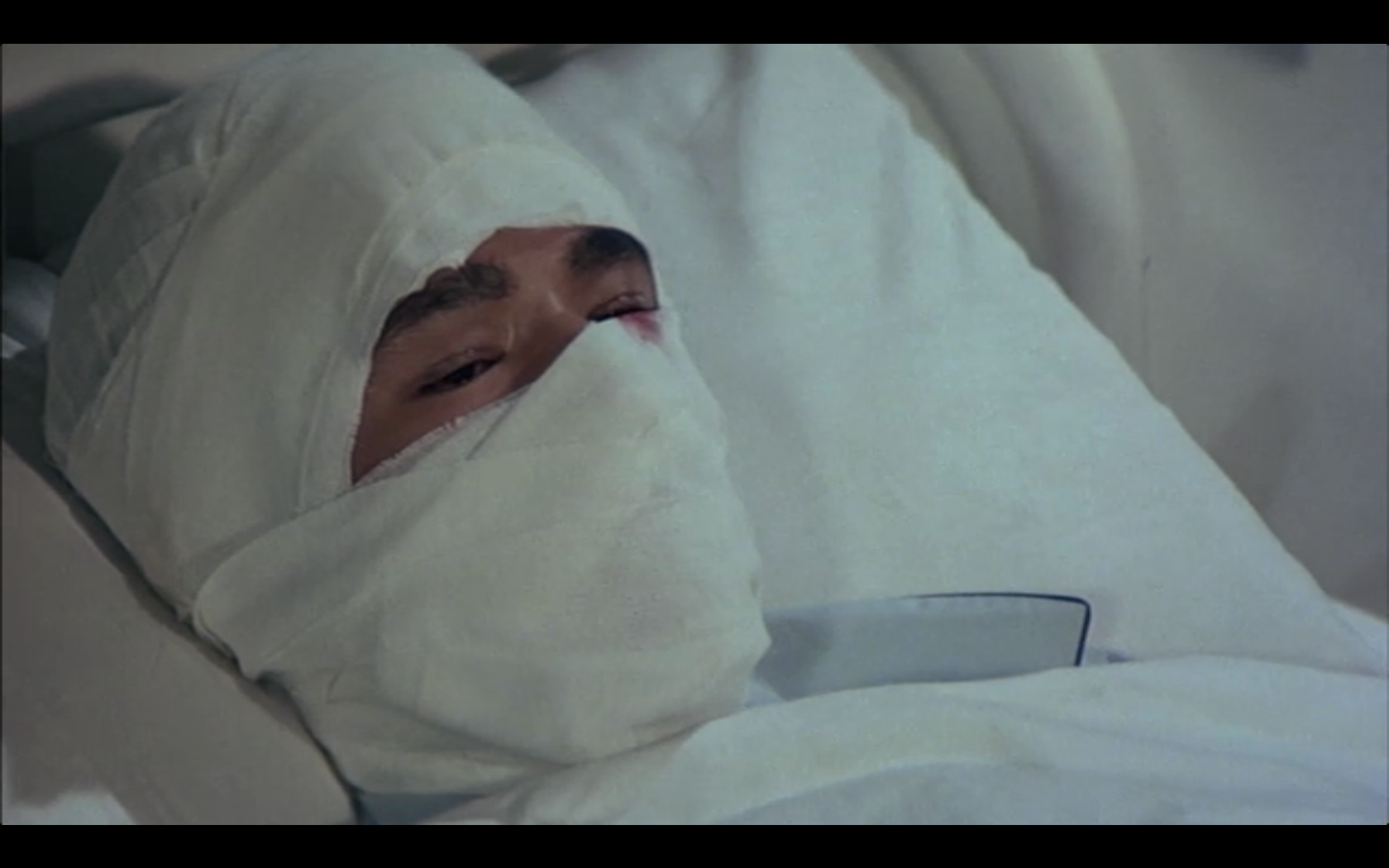

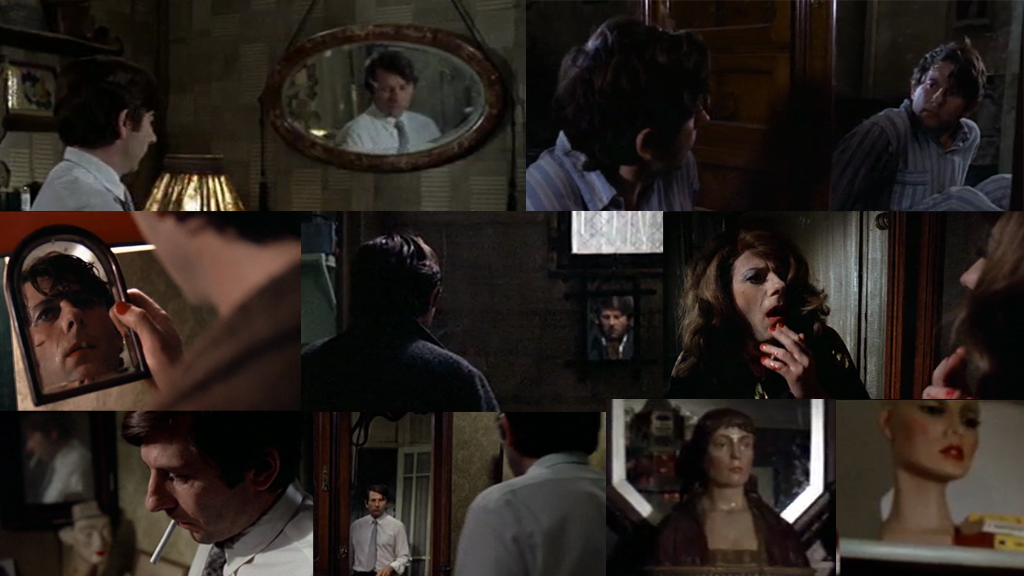

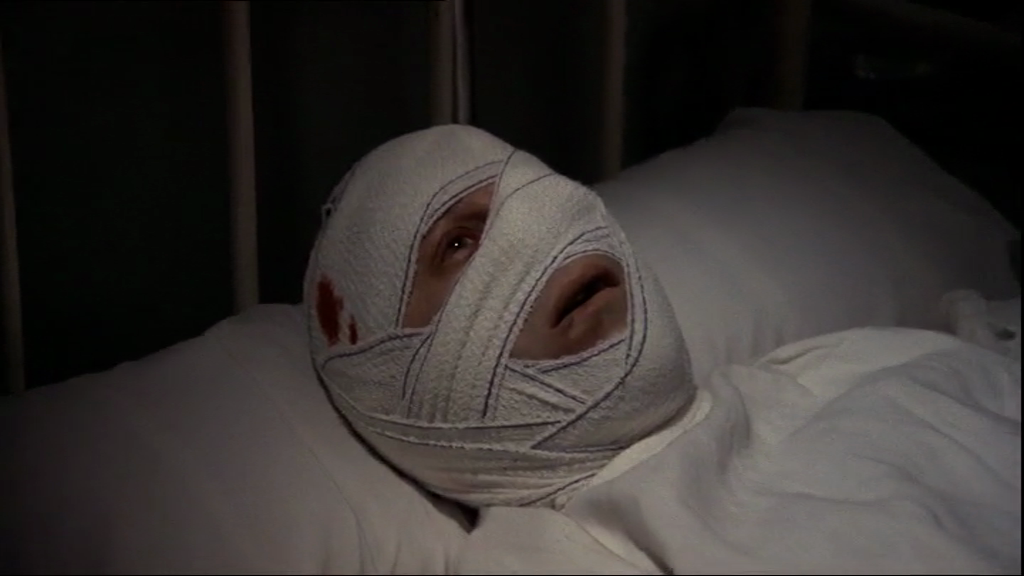

Take the scene where Billy Lo is recuperating in the hospital after being shot. It reminds me of Roman Polanski’s The Tenant, released three years after Bruce Lee’s death and two years before The Game of Death. The protagonist, Trelkovsky, moves into an apartment whose previous tenant, Simone Chule, recently attempted suicide. When Trelkovsky goes to visit the dying Simone at the hospital, he sees her face bound in bandages with a spot of blood, like Billy Lo’s.

After leaving the hospital, Trelkovsky takes a date to canoodle in a movie theater. The movie is Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon.

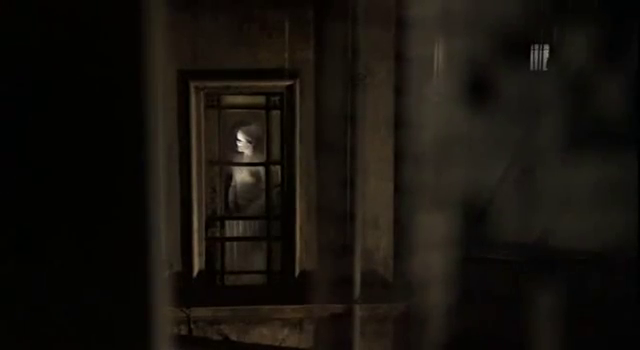

From that point on, Trelkovsky begins to descend into the paranoid delusion that his neighbors are overwriting his identity with Simone Chule’s. He disguises himself in Simone’s clothes and makeup, hallucinates his own severed head flying past his window, finds a tooth cached in a wall (Freud: “Dismembered limbs, a severed head, a hand cut off at the wrist… all these have something peculiarly uncanny about them”). When he looks at strangers, he sees his neighbors’ faces. He catches a double of himself spying into his apartment with binoculars. And he witnesses a girl forced to don a mask of his face.

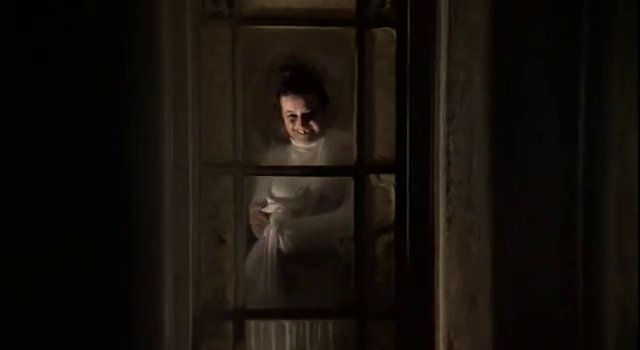

Eventually Trelkovsky’s paranoia fulfills itself, and he attempts suicide the same way ((Much of “The Uncanny” is spent analyzing ETA Hoffmann’s “The Sandman,” which resembles The Tenant. Its protagonist is a young man given to spying out his window, hallucinating malicious deeds, and mistaking people’s identities; he ultimately throws himself from a parapet to his death.)) Simone Chule does, falling from his window and crashing through a skylight ((Actually, he does it twice—certainly the double exposure to the curse, through both Simone Chule and Bruce Lee, accounts for this.))—which is like how The Game of Death ends with Billy Lo crashing through a mirror and chasing Dr. Land off of a roof to his death, and how The Crow begins with Eric Draven thrown through a window to his death, a fate he later visits on several villains. In the final shot, Trelkovsky winds up wound up in identical bandages, screaming as the camera careens into his mouth, entering his face.

Eventually Trelkovsky’s paranoia fulfills itself, and he attempts suicide the same way ((Much of “The Uncanny” is spent analyzing ETA Hoffmann’s “The Sandman,” which resembles The Tenant. Its protagonist is a young man given to spying out his window, hallucinating malicious deeds, and mistaking people’s identities; he ultimately throws himself from a parapet to his death.)) Simone Chule does, falling from his window and crashing through a skylight ((Actually, he does it twice—certainly the double exposure to the curse, through both Simone Chule and Bruce Lee, accounts for this.))—which is like how The Game of Death ends with Billy Lo crashing through a mirror and chasing Dr. Land off of a roof to his death, and how The Crow begins with Eric Draven thrown through a window to his death, a fate he later visits on several villains. In the final shot, Trelkovsky winds up wound up in identical bandages, screaming as the camera careens into his mouth, entering his face.

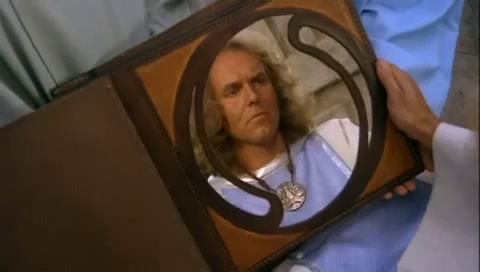

Other parallels abound. Both The Game of Death and The Tenant are about a man who, struggling against a dead person for possession of his identity, disguises himself and takes revenge. Bruce Lee is the only significant Asian character in a movie that’s set in China, and Trelkovsky is the only one with a European accent in Paris. The dialogue in both movies is largely dubbed. Bruce Lee is credited as Billy Lo even though he barely appears, while Roman Polanski, as Trelkovsky, is cryptically uncredited. And both films feature several significant shots of the protagonists gazing into mirrors and of disembodied fake heads.

There’s even a real-life connection between the two films, as with The Crow: Bruce Lee personally instructed Roman Polanski in kung fu (yes, really).

So, did Bruce Lee influence The Tenant? Did The Tenant influence The Game of Death? Let’s go even further than that. Maybe The Game of Death is actually contiguous with The Tenant, a movie that’s cyclical to begin with. Billy Lo somehow curses or possesses Simone Chule and Trelkovsky. Sort of like a mummy ((The word “mummy” derives from the Persian mūm, meaning “wax,” which was used as a mummifying medium, and which we now use to make uncanny doppelgangers of famous people. (Now Dr. Land’s wax-sculpting hobby in The Game of Death makes more sense!) While we’re at it: “behold” derives from the Middle English bihaldan, meaning to watch, but also to bind or possess, like a mummy. To be shot in a film is to be eternally bound to be beheld. And “visage” comes from the Latin videre, to see. Etymology is a line of sequels, a lineage of connotations, the latest usage always a shade of its progenitor.))—mummies curse you when you behold them, and they can possess their victims, overwriting their identities. The implication that Simone is a mummy is pretty much spoon-fed to us: she’s an Egyptologist, she’s wrapped in bandages, and Trelkovsky finds hieroglyphics in a bathroom in which she later appears, unwinding her bandages to reveal her damaged face:

Suppose, then, that Bruce Lee and Simone Chule are both mummies. When Trelkovsky visits Simone and then sees Enter the Dragon, he becomes doubly cursed to doubleness. Now The Tenant’s central mystery—why Trelkovsky believes he’s being possessed—comes clear: it’s not psychopathology, but a vision of the occult. Like Billy Lo, Trelkovsky’s identity becomes displaced by a dead person who, lacking a face of its own, claims his.

Suppose, then, that Bruce Lee and Simone Chule are both mummies. When Trelkovsky visits Simone and then sees Enter the Dragon, he becomes doubly cursed to doubleness. Now The Tenant’s central mystery—why Trelkovsky believes he’s being possessed—comes clear: it’s not psychopathology, but a vision of the occult. Like Billy Lo, Trelkovsky’s identity becomes displaced by a dead person who, lacking a face of its own, claims his.

Midway through The Tenant, Trelkovsky delivers a soliloquy:

Tell me: at what precise moment does an individual stop being who

he thinks he is? Cut off my arm: I say, Me and my arm. You cut off my

other arm: I say, Me and my two arms. You take out my stomach, my

kidneys, assuming that were possible, and I say, Me and my intestines.

Follow me? And now, if you cut off my head, would I say Me and my

head or Me and my body? What right has my head to call itself me?

What right?

Was Bruce Lee a head—a set of experiences, knowledge, a face—that used its body as an instrument, or was he a honed body with an interchangeable head, or both, or neither? In my previous essay, I pointed out that Billy Lo fakes his own death by planting a clay head in a coffin, and that the clay head is later ironically played by the real Bruce Lee’s corpse. Trelkovsky’s meditation on the seat of identity in the body might be extended further: if I have an image of my body, do I need a body at all? What right does my body have to call itself me? What right does Bruce Lee’s head have to call itself Bruce Lee, when a clay head, his own dead face, or no face at all would do? What right?

You possess your face—while you live. But in images a face outlasts its original tenant. Upon death, possession reverts to the beholder, and to behold is to possess.

———

We’ve established that Billy Lo is a mummy who can possess others on sight; that his influence extends beyond the immediate neighborhood of The Game of Death and into other movies; and that mummies don disguises and live beyond the grave. This might explain why the uncanny parallels between The Game of Death and its sequels, The Crow and The Tenant, uncannily parallel the uncanny parallels within The Game of Death: it’s a contagious curse, and the human face is its vector.

With these points of reference, we might be able to triangulate Billy’s presence in other narratives by hunting for doubles, disguises, multiple identities, deaths, resurrections, transfigurations, and possessions. On those subjects, the first that come to mind are Vladimir Nabokov (Pale Fire, Ava, “Spring in Fialta,” “The Vane Sisters”) and Stanley Kubrick (Dr. Strangelove, The Shining, Eyes Wide Shut); conveniently, we have Kubrick’s 1962 adaptation of Lolita. Like The Game of Death, the first shot opens with a disclaimer explicitly announcing its coincidental nature: THE EVENTS AND CHARACTERS DEPICTED IN THIS PHOTOPLAY ARE FICTITIOUS. ANY SIMILARITY TO PERSONS LIVING OR DEAD IS PURELY COINCIDENTAL. As in The Tenant, Lolita’s first intimate contact comes when she seizes Humbert’s leg while watching a movie—Humbert scratches his face and pats her hand, and when they withdraw, as if he’s transmitted something to her, Lolita scratches her own face the same way. (What are they watching? Oh man, I’ll tell you later.)

There’s plenty that’s mummylike about Humbert and Lolita. Humbert is a tenant, and the successor of a past incarnation (Lolita’s father, whom he uncannily resembles); Lolita (or Lo, as she’s called) is the reincarnation of Humbert’s childhood love Annabel Leigh, who in turn is a resurrection of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Annabel Lee”—so we have a Lo and a Lee, shades of the same person. (“What drives me insane is the twofold nature of this nymphet,” Humbert writes of Lolita in his diary—“of every nymphet, perhaps.”)

There’s plenty that’s mummylike about Humbert and Lolita. Humbert is a tenant, and the successor of a past incarnation (Lolita’s father, whom he uncannily resembles); Lolita (or Lo, as she’s called) is the reincarnation of Humbert’s childhood love Annabel Leigh, who in turn is a resurrection of Edgar Allen Poe’s “Annabel Lee”—so we have a Lo and a Lee, shades of the same person. (“What drives me insane is the twofold nature of this nymphet,” Humbert writes of Lolita in his diary—“of every nymphet, perhaps.”)

With respect to The Game of Death and The Crow, we can also appreciate the scene where Humbert decides to “accidentally” load a bullet into a gun to murder Charlotte Haze, or when Humbert, learning of Lolita’s departure, fights to conceal his disappointment. “Is something the matter with your face?” Charlotte asks him, and he replies (perhaps feeling Simone Chule’s shade pass over him), “Toothache.” Even the novel Lolita itself is a twofold double—of Heinz von Lichberg’s 1916 short story “Lolita,” and of Nabokov’s stillborn novella The Enchanter—and has its own double in Nabokov’s final completed novel, which is titled (evoking the harlequin masks in The Tenant, The Crow, and The Game of Death) Look at the Harlequins! ((Nabokov is the consummate gamester. In Pale Fire, the delusional Charles Kinbote lavishly misreads a posthumous 999-line poem by his neighbor John Shade. Shade denotes both a shadow—an insubstantial double, dependent on the original—and a ghost. The poem begins: “I was the shadow of the waxwing slain / by the false azure in the windowpane / I was the smudge of ashen fluff—and I / lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.” The original dies encountering its reflection; the shade lives on. Mistaken for someone else, Shade is assassinated in an attack that evokes the mistargeted assassination of Vladimir Nabokov’s father, Vladimir Nabokov. (The date of Shade’s murder is Nabokov’s father’s birthday.)

With respect to The Game of Death and The Crow, we can also appreciate the scene where Humbert decides to “accidentally” load a bullet into a gun to murder Charlotte Haze, or when Humbert, learning of Lolita’s departure, fights to conceal his disappointment. “Is something the matter with your face?” Charlotte asks him, and he replies (perhaps feeling Simone Chule’s shade pass over him), “Toothache.” Even the novel Lolita itself is a twofold double—of Heinz von Lichberg’s 1916 short story “Lolita,” and of Nabokov’s stillborn novella The Enchanter—and has its own double in Nabokov’s final completed novel, which is titled (evoking the harlequin masks in The Tenant, The Crow, and The Game of Death) Look at the Harlequins! ((Nabokov is the consummate gamester. In Pale Fire, the delusional Charles Kinbote lavishly misreads a posthumous 999-line poem by his neighbor John Shade. Shade denotes both a shadow—an insubstantial double, dependent on the original—and a ghost. The poem begins: “I was the shadow of the waxwing slain / by the false azure in the windowpane / I was the smudge of ashen fluff—and I / lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.” The original dies encountering its reflection; the shade lives on. Mistaken for someone else, Shade is assassinated in an attack that evokes the mistargeted assassination of Vladimir Nabokov’s father, Vladimir Nabokov. (The date of Shade’s murder is Nabokov’s father’s birthday.)

Nabokov also left an unfinished novel, The Original of Laura, about a professor’s obsession with a past love and the idea of metaphysically wiping himself out—the narrator calls it an “absorption into the divine essence.” (Its working title was Dying is Fun—if dying is fun, perhaps death is a game.) In 2009, Nabokov’s son Dmitri released the unfinished manuscript, claiming that his “father… or his father’s shade” would not have minded. Previously Dmitri had resuscitated The Enchanter, which Nabokov considered a “dead scrap.”

Dmitri himself lived multiple lives: teacher, chaplain’s assistant, author and translator, racecar driver, opera singer. Three years after his father’s death, having failed to carry out his father’s wishes to incinerate The Original of Laura, Dmitri had a racecar accident that covered him in third-degree burns. He claimed to have briefly died after the accident, but convalesced in the same hospital his father died in, presumably wrapped in bandages. After his own death in 2012, it was discovered that Dmitri had published writing under pseudonyms.

Liberally misinterpreting one of Shade’s couplets, Pale Fire’s Kinbote quips, “our poet suggests here that human life is but a series of footnotes to a vast obscure unfinished masterpiece.” Perhaps The Game of Death, The Crow, The Tenant, and Lolita are not discrete entities, but the capillaries in a circulatory system, a divine essence into which everything returns.))

But I want to talk about Clare Quilty, a character whose role is amplified in Kubrick’s adaptation. A sleazy playwright, Quilty is Humbert’s shade: like Humbert, he’s a pedophile who pursues Lolita and eventually steals her away. Quilty is played by Peter Sellers, who was notorious for playing multiple roles in films, and once declared that he had no personality of his own, only those of his characters. (“The person takes over,” Sellers said, describing the process of finding his way into a role. “The man you play begins to exist.”) Accompanied by Nabokov’s anagrammatic double Vivian Darkbloom, Quilty variously disguises himself as a cop, a Teutonic psychoanalyst (who would know all about the Uncanny), and a phone surveyor.

Impersonating the cop (and turned away so that Humbert can’t see his face), Quilty teasingly questions Humbert about Lolita, and remarks: “I notice human individuals. And I noticed your face. I said to myself when I saw you, there’s a guy with the most normal-looking face I ever saw in my life… It’s great to see a normal face, cause I’m a normal guy.” Superficially, the gag is that people aren’t noticed for looking normal. But Quilty notices Humbert for having a “normal-looking face,” for being a “human individual” (just as the doctor in The Game of Death insists that Billy Lo will have a “normal appearance”), while Quilty himself, a habitual disguiser played by a habitual disguiser, possesses multiple assumed identities.

Impersonating the cop (and turned away so that Humbert can’t see his face), Quilty teasingly questions Humbert about Lolita, and remarks: “I notice human individuals. And I noticed your face. I said to myself when I saw you, there’s a guy with the most normal-looking face I ever saw in my life… It’s great to see a normal face, cause I’m a normal guy.” Superficially, the gag is that people aren’t noticed for looking normal. But Quilty notices Humbert for having a “normal-looking face,” for being a “human individual” (just as the doctor in The Game of Death insists that Billy Lo will have a “normal appearance”), while Quilty himself, a habitual disguiser played by a habitual disguiser, possesses multiple assumed identities.

Therefore we’re hardly surprised that the movie begins and ends with Humbert shooting Quilty in the face. Humbert intrudes into Quilty’s mansion and demands, “Are you Quilty?”

“No, I’m Spartacus,” Quilty says—and here let me point out that Lolita is Kubrick’s follow-up to Spartacus, whose most famous scene has multiple men indistinguishably posing as one man.

When he realizes his banter won’t save him, Quilty dives for cover behind a portrait; the woman in the portrait is shot in the same part of her face as Billy Lo, and Quilty is fatally shot in his face through her face. As well as writing plays, Quilty made smutty films; if he was working on one when he died, he left it unfinished.

If there’s a mummy in Lolita, how did it get in? Was the curse retroactively transmitted through Shelley Winters, who later appeared as Trelkovsky’s concierge in The Tenant? Nah—let’s go back to the scary movie that Lolita and Humbert watch. It’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), starring Christopher Lee—specifically, the scene in which the resurrected, mummy-bandaged Frankenstein’s monster unwraps his head (like Simone Chule) to reveal his scarred face (like Billy Lo’s), which is missing a tooth (like Simone Chule’s):

Frankenstein is a resurrected mummy, so we know just what kind of curse The Curse of Frankenstein delivers. This film was the first of Hammer Films’ occult classics, the third of which was, naturally, a reboot of The Mummy, starring Christopher Lee.

Frankenstein is a resurrected mummy, so we know just what kind of curse The Curse of Frankenstein delivers. This film was the first of Hammer Films’ occult classics, the third of which was, naturally, a reboot of The Mummy, starring Christopher Lee.

Yes, let’s go back to the cinematic source: The Mummy (1932), a franchise that’s been spun off nearly as often as Bruce Lee. ((The best known series are the original Universal series, the Hammer Horror revivals, and the recent Stephen Sommers reboot, the second installment of which is The Mummy Returns. Universal announced plans for yet another reboot.))

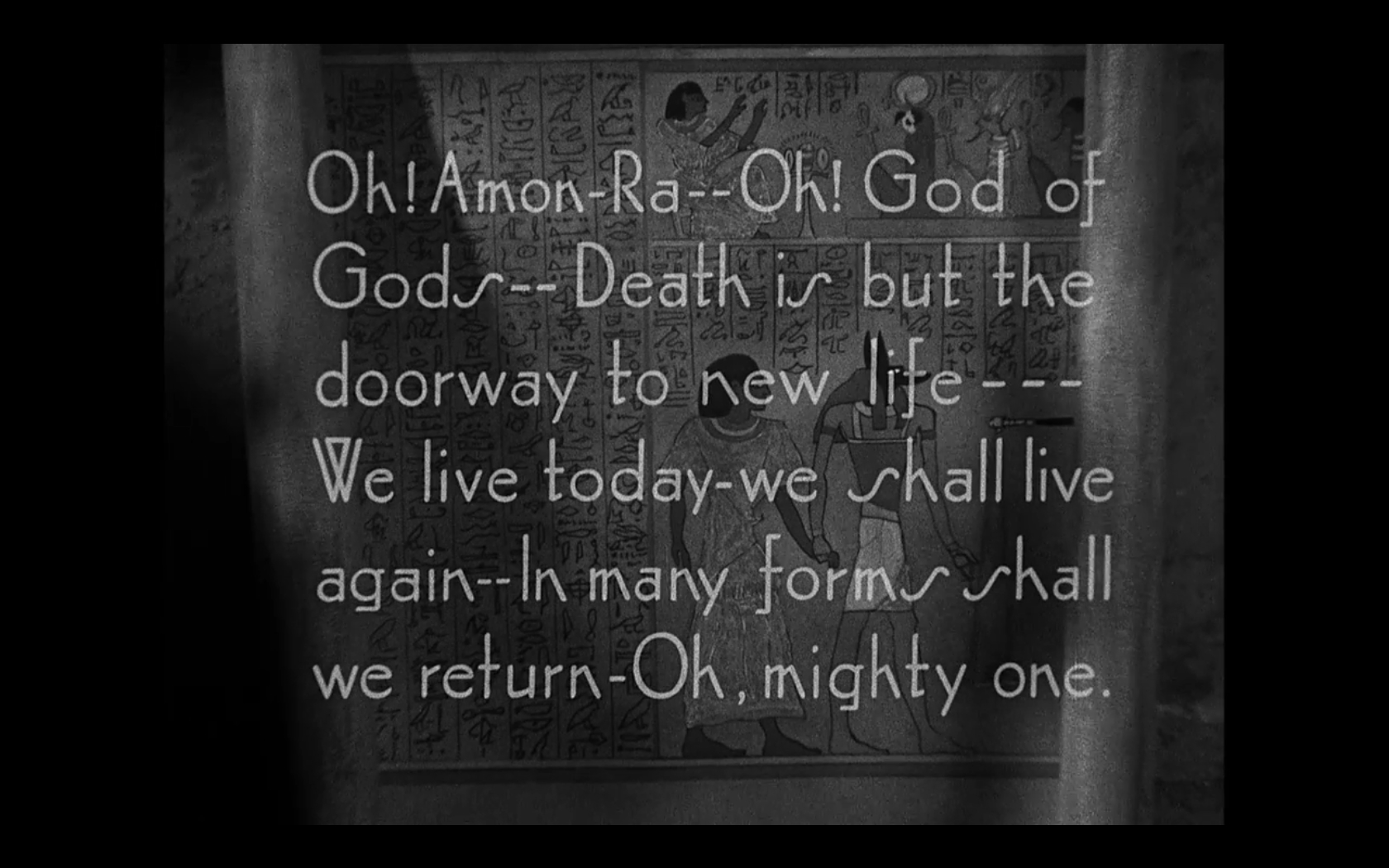

Boris Karloff, who plays the titular mummy, is billed on the movie’s poster as “Karloff the Uncanny.” Like Lolita and The Game of Death, the film opens with a disclaimer: ((Might as well mention that there’s a Wesley Snipes movie called Game of Death (2010), totally unremarkable except in that Wesley Snipes’s production studio is called Amen-Ra.))

In The Mummy, the Egyptian priest Imhotep is wrapped in bandages and buried alive as punishment for attempting to resurrect his dead lover, Princess Ankh-es-en-amon.

In The Mummy, the Egyptian priest Imhotep is wrapped in bandages and buried alive as punishment for attempting to resurrect his dead lover, Princess Ankh-es-en-amon.

Imhotep is dug up 3,700 years later by archaeologists from the British Museum; a reckless assistant recites the hieroglyphics on a magic scroll, and is driven hysterical when Imhotep returns from the dead (“He went for a little walk—you should have seen his face!”). After escaping and assuming a false identity, Imhotep plots to reawaken the memories of his reincarnated princess, a young woman named Helen Grosvenor. Delivering Jedi force-chokes to all who oppose him, Imhotep succeeds in possessing Helen, but is ultimately stymied by her last-minute refusal to sacrifice her mortal body. (Her old body is interred in a coffin resembling the one that’s on the postcard Trelkovsky receives, addressed to Simone Chule.) Helen supplicates a statue of Isis, which blasts Imhotep’s face right off his skull, roll credits.

Imhotep is dug up 3,700 years later by archaeologists from the British Museum; a reckless assistant recites the hieroglyphics on a magic scroll, and is driven hysterical when Imhotep returns from the dead (“He went for a little walk—you should have seen his face!”). After escaping and assuming a false identity, Imhotep plots to reawaken the memories of his reincarnated princess, a young woman named Helen Grosvenor. Delivering Jedi force-chokes to all who oppose him, Imhotep succeeds in possessing Helen, but is ultimately stymied by her last-minute refusal to sacrifice her mortal body. (Her old body is interred in a coffin resembling the one that’s on the postcard Trelkovsky receives, addressed to Simone Chule.) Helen supplicates a statue of Isis, which blasts Imhotep’s face right off his skull, roll credits.

Like Christopher Lee, Karloff the Uncanny’s hollow-eyed face ((This face must have possessed the movie’s other actors as well. David Manners, who plays Helen’s love interest, also starred in The Death Kiss (1932), in which a movie star is shot dead on the film set in plain view of everyone while the camera rolls, as in The Game of Death and Brandon Lee’s accidental death.)) made him famous for his portrayals of the Mummy, Frankenstein, and a grotesque yellowface Fu Manchu in the hintingly named The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), in which Fu Manchu races Detective Nayland Smith and the Egyptologist Dr. Petrie ((Dr. Petrie, coincidentally, is the name of another Egyptologist in another film, The Mummy’s Hand (1940), the first in a series of Universal Studios mummy reboots. The sequel, The Mummy’s Ghost (1944), featured John Carradine as Yousef Bey. And yes, John Carradine was the father of David; more later.)) to find the mask and sword of a mummified Genghis Khan, thus becoming deliberately possessed by his spirit. Christopher Lee, on the other hand, starred as Fu Manchu in The Face of Fu Manchu (1965), in which Fu Manchu fakes his execution by replacing himself with an Asian body double.

Since my last essay began with a discussion of Asian men and yellowface in cinema, it’s no surprise that we’ve returned to the Asian villain par excellence, Fu Manchu. The roles that Eastern characters play in these mummy movies suggest a link between occult and Orient: Trelkovsky is a Polish man in France, Humbert is a European in America, Imhotep an Egyptian among Westerners. So the practice of yellowface seems ripe for mummyism.

Thus we return to one of our established mummies, Peter Sellers. His own posthumous movie, The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu (1980), is an oh-my-god-crazy-offensive yellowface farce starring a 168-year-old Fu Manchu, and is full of gong blasts, casual racial slurs, and eyelid tape. This two-hour piece of shit is based on a novel by Sax Rohmer, the pseudonymous creator of Fu Manchu (first published story: “The Mysterious Mummy”), and has Sellers playing both Fu Manchu and Nayland Smith, longtime nemeses. “He is evil to my good, yea to my nay, yin to my yang,” Smith remarks, having had a previous clash with Fu Manchu in—where else?—a pyramid in Egypt.

Fu Manchu and Smith deploy disguises, dacoits, and decoys to outwit each other: Helen Mirren, for instance, plays a police constable, Helen Rage, who plays a decoy of Queen Elizabeth II ((Decades later, Mirren played Queen Elizabeth II in The Queen. And what is a monarchy but a line of homonymic successors?)); both share their names with The Mummy’s Helen Grosvenor.

Fu Manchu and Smith deploy disguises, dacoits, and decoys to outwit each other: Helen Mirren, for instance, plays a police constable, Helen Rage, who plays a decoy of Queen Elizabeth II ((Decades later, Mirren played Queen Elizabeth II in The Queen. And what is a monarchy but a line of homonymic successors?)); both share their names with The Mummy’s Helen Grosvenor.

Again there are telltale resonances between this film and others in our expanding mummyverse. The film opens as Fu Manchu, whose ludicrous weeping-willow hair resembles the geezered-up Billy Lo’s, is about to be administered a longevity elixir by one of his Si-Fan ((“The most diabolical secret Oriental organization in the world,” and a near-homophone of Bruce Lee’s original genderqueered birth name, Sai Fon.)) dacoits. “Your face is familiar,” Fu Manchu tells him for no reason ((No reason within the movie, I mean. It’s most likely a reference to the fact that the extra, Burt Kwouk, acted alongside Sellers in The Pink Panther and appeared in two Fu Manchu films. This is another example of the phenomenon of the uncanny double vision that marks a mummy sighting: Fu Manchu can apprehend Kwouk’s familiarity, but not his identity.)); when the bumbling servant accidentally destroys the elixir, an enraged Fu Manchu commands his other servants to “bury him alive in the red ant hill”—which resembles Imhotep’s punishment.

Again there are telltale resonances between this film and others in our expanding mummyverse. The film opens as Fu Manchu, whose ludicrous weeping-willow hair resembles the geezered-up Billy Lo’s, is about to be administered a longevity elixir by one of his Si-Fan ((“The most diabolical secret Oriental organization in the world,” and a near-homophone of Bruce Lee’s original genderqueered birth name, Sai Fon.)) dacoits. “Your face is familiar,” Fu Manchu tells him for no reason ((No reason within the movie, I mean. It’s most likely a reference to the fact that the extra, Burt Kwouk, acted alongside Sellers in The Pink Panther and appeared in two Fu Manchu films. This is another example of the phenomenon of the uncanny double vision that marks a mummy sighting: Fu Manchu can apprehend Kwouk’s familiarity, but not his identity.)); when the bumbling servant accidentally destroys the elixir, an enraged Fu Manchu commands his other servants to “bury him alive in the red ant hill”—which resembles Imhotep’s punishment.

A few scenes later at the British Museum (the same museum that employs The Mummy’s archaeologists), we see six barefoot Si-Fan pallbearing a coffin-sized box, not unlike the pallbearers from The Game of Death. One of the dacoits offers the museum guard fake credentials and tells him, “We bring it back to you when Restoration Society make sure it not fake.” And what are the dacoits stealing?:

The mummy is an ingredient in Fu Manchu’s longevity elixir, which restores his youth, with a side effect: the face-clutchingly awful finale has Fu Manchu inexplicably possessed by Elvis. Thus Fu Manchu, the West’s caricature ((As long as we’re on Fu Manchu, we can also contemplate his archetypal inverse: the obsequious Charlie Chan, most famously played by a yellowface Warner Oland, who’d also played Fu Manchu. Bruce Lee was screentested for the part of Charlie Chan’s “Number One Son”—a role he would’ve inherited from Keye Luke. Luke would go on to become the first Asian actor to play Charlie Chan, the same year he played David Carradine’s mentor Master Po in Kung Fu, and one year before overdubbing the voice of the lead villain in Enter the Dragon, who fights by hiding in a hall of mirrors.)) of Asian supremacism, assumes a caricature of white culture—yellowface in whiteface.

The mummy is an ingredient in Fu Manchu’s longevity elixir, which restores his youth, with a side effect: the face-clutchingly awful finale has Fu Manchu inexplicably possessed by Elvis. Thus Fu Manchu, the West’s caricature ((As long as we’re on Fu Manchu, we can also contemplate his archetypal inverse: the obsequious Charlie Chan, most famously played by a yellowface Warner Oland, who’d also played Fu Manchu. Bruce Lee was screentested for the part of Charlie Chan’s “Number One Son”—a role he would’ve inherited from Keye Luke. Luke would go on to become the first Asian actor to play Charlie Chan, the same year he played David Carradine’s mentor Master Po in Kung Fu, and one year before overdubbing the voice of the lead villain in Enter the Dragon, who fights by hiding in a hall of mirrors.)) of Asian supremacism, assumes a caricature of white culture—yellowface in whiteface.

The film was released a month after Sellers’s death to a proportionately lousy reception; some critics attributed Sellers’s limp performance and gauntness to his failing health. A dying man played a dying man, and again, the character survives the actor.

———

The trail goes on indefinitely. You could play this game, going from death to death, until you died. We could follow it through Polanski: consider the female doppelgangers and facial injuries in Chinatown, and the uncanny similarities between the films in his Apartment Trilogy. Or Kubrick: the twins and the cycle of possessions in The Shining; or the posthumous ((Kubrick also left the unfinished A.I., a Pinocchio picaresque about an android who wants to become human—he winds up entombed undersea until he’s unearthed 2,000 years later. After Kubrick’s death, the project fell to Stephen Spielberg, who said he felt as if he were “being coached by a ghost.”)) Eyes Wide Shut, a literal orgy of masks and disguises, featuring a scene where a costume store owner walks in on his teenage daughter engaged in a sexual dalliance with two cross-dressing Asian men—a tidy nexus of Lolita, The Tenant, and The Game of Death.

But we no longer need to seek out mummies; they’ve overrun us. There’s Nina Sayers in Black Swan ((Darren Aronofsky cites The Tenant as an influence on Black Swan. And in June 2009, around when Universal resurrected the production of Black Swan—Aronoksky said it had “sort of died”—an Internet rumor circulated that Natalie Portman had fallen off a cliff to her death while filming a movie.)), who competes with her double for the dual role of Black and White Swan, hallucinates an autonomous reflection in mirrors, and conceals her face in makeup; Natalie Portman’s stunt double has her face digitally replaced with Portman’s, like Bruce and Brandon Lee’s body doubles. Oscar ((Leos Carax has said, “If Denis [Lavant] had said no, I would have offered the part to Lon Chaney or to Chaplin. Or to Peter Lorre or Michel Simon, all of whom are dead.” Lon Chaney played the mummy Kharis in Universal’s 1940s revivals of The Mummy, as well as the yellowface lead in Mr. Wu, while Peter Lorre did his yellowface turn in Mr. Moto.)) in Holy Motors assumes disguises and acts out surreal scenarios, appearing to die and revive repeatedly. Samara in The Ring remake is a returned videoborne mummy who murders people at a glance with her scarred face, leaving her victims with scarred faces of their own. The Invisible Man, Hamlet ((Especially Kenneth Branaugh’s adaptation.)), Jesus, Huckleberry Finn. I’ve never seen John Woo’s Face/Off, but it seems a likely sarcophagus, as it stars Nicolas Cage ((In 2013, Cage purchased a pyramid that he intends to be buried in. Its inscription reads “OMNIA AB UNO,” or “ALL FROM ONE.”)), who also did a brief cameo as Fu Manchu in Quentin Tarantino’s Grindhouse… Tarantino also directed Kill Bill, whose heroine fakes her own death, gets shot in the face, becomes comatose, is buried alive, goes by pseudonyms, and massacres 88 masked Asians while wearing a facsimile of Bruce Lee’s tracksuit from The Game of Death.

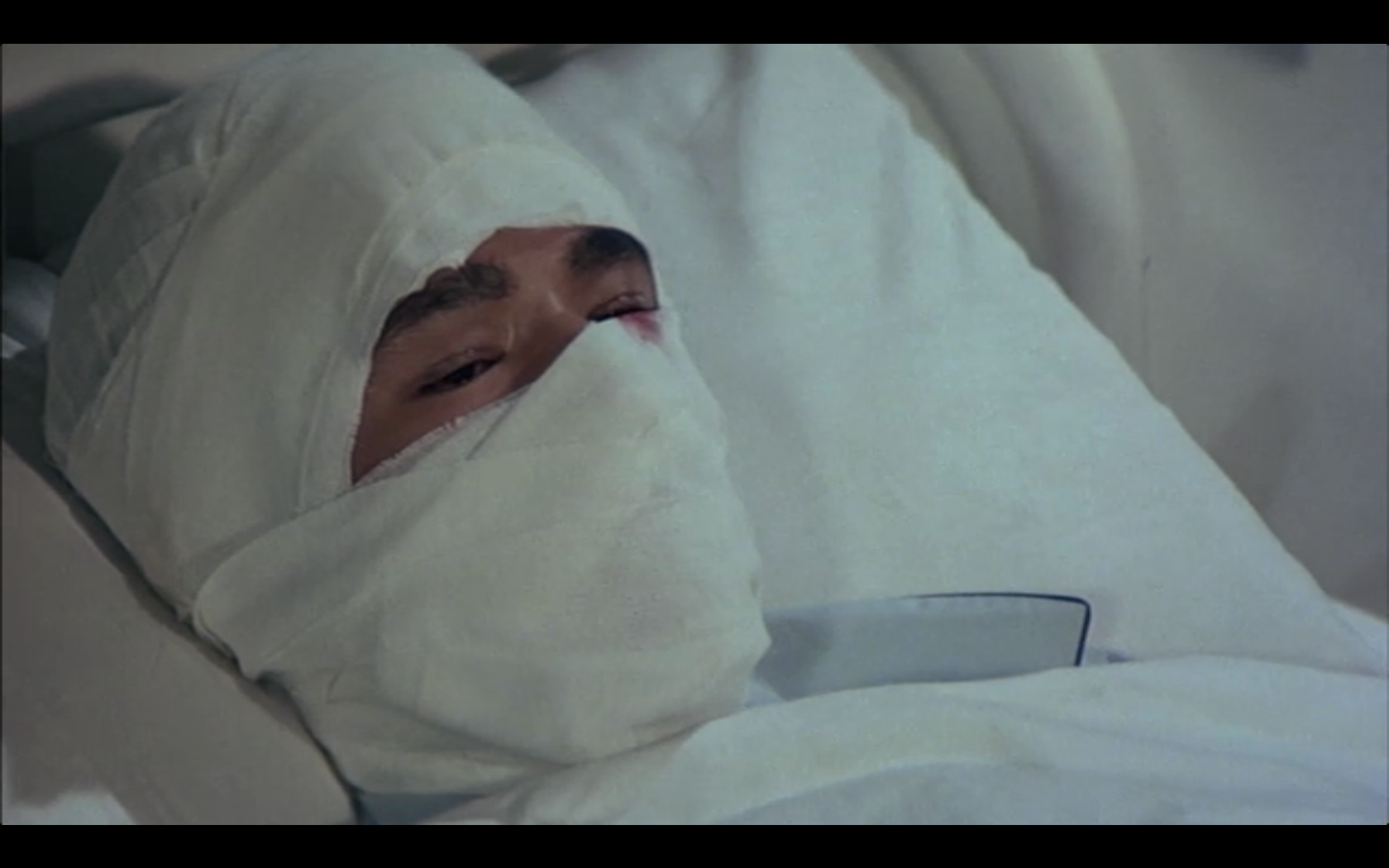

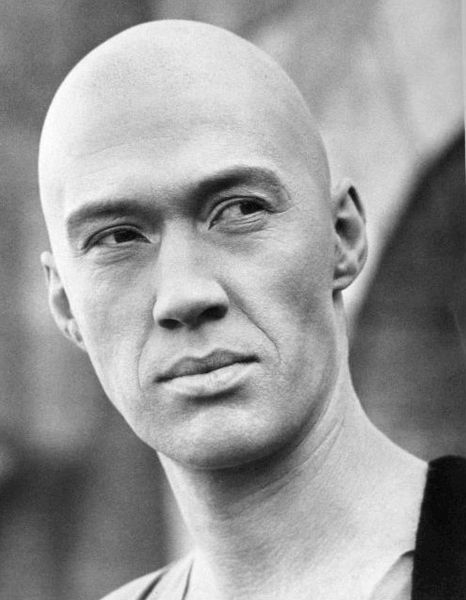

Suffice it to return to a double. For it turns out that Bruce Lee has not one, but two posthumous films—in 1970 he wrote a screenplay called The Silent Flute. This was his take on Eastern philosophy, featuring lots of Zen-flavored profundities and plenty of violence (“The second thug writhes on the ground, doubled in upon himself, his genitals destroyed”—well that’s one way to silence a flute ((Silent flute was Elizabethan slang for penis. Asian males possess another stereotyped body part—the penis, which Freud claims is interchangeable with the face. Lee was never above dishing out groin-shots in battle; I’ll bet he never takes one, but I’m not going to fact-check that.)) ). Lee decided not to produce the movie, but the project was revived and released in 1978, the same year as The Game of Death, with the title Circle of Iron, starring David Carradine.

Most remember Carradine, if not for his comeback as Bill in Kill Bill (in which his face is mostly concealed), then as the actor who launched a career in yellowface as Kwai Chang Caine in the TV series Kung Fu. Carradine ate Bruce Lee’s lunch in all sorts of ways: Lee originally conceived Kung Fu as The Warrior, but was rejected for the lead role because Warner Brothers deemed American audiences unready for an Asian man playing an Asian man—they favored the more “serene” Carradine ((Ed Spielman, the credited creator of Kung Fu, disputes this account. I guess it’s possible they independently pitched movies about a wandering Chinese martial artist exiled in the American West to Warner Bros. at the same time—but, hmm. At any rate, regarding the decision not to cast an actual Asian, ABC’s Vice President reportedly said, “If we put a yellow man up on the tube, the audience will turn the switch off in less than five minutes.”)). Caine’s grandfather is played by Dean Jagger (who played Dr. Land), and in Kung Fu: The Movie, Carradine starred alongside Brandon Lee, who played Caine’s son. (That’s right: Carradine played the role of Brandon Lee’s father while playing Brandon Lee’s father’s role.) Brandon Lee then went on to play his own grandson in Kung Fu: The Next Generation, while Carradine played his own grandson, also named Kwai Chang Caine, in Kung Fu: The Legend Continues. In his memoir years later, Carradine wrote: “I was a fake. When I left the series after four years I knew nothing about kung fu.” (Though he spawned fakes of his own—an Asian Caine impersonator stars alongside the Bruce Lee impersonator in The Dragon Lives On.)

The misadventures in Carradine’s biography do suggest a curse. He claimed to have tried hanging himself at the age of five after discovering that he and his brother Bruce (!) had different fathers; and in June 2009 ((The same month that Black Swan was put back into production and the Portman death rumor went viral.)), four months after asserting in a TV interview that his bedroom closet at home was haunted by his wife’s previous husband ((“Some things were breaking. Mainly glass. Glass was breaking all the time… [my wife] said that he’s pissed off, because he had these twins, and almost right after they were born he gets pancreatic cancer and spent a year in the hospital. Then he died and now he’s really pissed off.”)), he was found dead of autoerotic asphyxiation in his hotel room closet. He was in the final days of shooting the film Stretch, set in Macau, where part of The Game of Death is set. The final film was edited so that Carradine’s character is discussed, but seldom seen; one scene includes an incidental radio broadcast that announces, “The actor David Carradine is dead.”

But enough—let’s complete our circle of ironies. “The spirit of Bruce Lee lives in The Circle of Iron!” announces the trailer; and it lives in Carradine, who plays multiple roles as a blind wanderer, a monkey man, a Gypsy leader, and Death, sages who guide a musclehead named Cord on his pilgrimage. Bruce Lee’s envisioned Thai setting is replaced with a fantasy setting, but is nonetheless populated with the full summer catalog of Orientalist yellowface stereotypes. Along the way we find The Game of Death’s meta-doubletalk: when Cord encounters David Carradine as Death in the form of a panther, Cord taunts: “Why are you so ugly? Or do you have a different face for every man?” And after Cord laments breaking his vow of chastity, blind-wanderer Carradine quips, “You do not, cannot possess even yourself; how can you hope to possess anyone or anything else?” At the end of the film Cord finally meets Zetan, a monk who owns a book containing all the world’s wisdom, and is played by Christopher Lee, A.K.A. Fu Manchu, A.K.A. Kharis the Mummy, A.K.A. the mummified Frankenstein’s monster who appears in Lolita. The pages of Zetan’s book are all mirrors. “What did you see?” Carradine’s blind wanderer asks Cord; “Everything!” Cord replies.

The movie, in every regard a fucking travesty, is set to be revived in 2013 as The Silent Flute, with a new post-apocalyptic setting.

Mummies: A Field Guide

Everything I have done until now has been fruitless. It has led to nothing. There was no other path except that it led to nothing—and before me now there is only one real fact—Death. The truth I have been seeking—this truth is Death. Yet Death is also a seeker. Forever seeking me. So—we have met at last. And I am prepared. I am at peace. Because I will conquer death with death. —Cord, The Silent Flute

A hero looks death in the face, real death, not just the image of death. Behaving honorably in a crisis doesn’t mean being able to act the part of a hero well, as in the theatre, it means being able to look death itself in the eye. For an actor may play lots of different roles, but at the end of it all he himself, the human being, is the one who has to die. —Ludwig Wittgenstein

We’re now ready to describe the mummy: how to identify them, and how they work, behave, and propagate. There are five distinct stages in its lifecycle:

Possession: Upon beholding a mummy’s face, usually in the form of a doppelganger, the mummy-to-be undergoes an uncanny shock, seeing something she shouldn’t have seen—her own dead face or fake face or non-face, either on her own or someone else’s body, the appearance of a mummy. Occasionally seeing a dead loved one has the same uncanny effect.

Fake Death: An interval of dormancy, often cocooned in bandages and/or entombed. Nightmares may result. (Freud characteristically relates this to both the fear of death and a return to the womb, and adds, “To some people the idea of being buried alive by mistake is the most uncanny thing of all.”)

Imago: Emerging impassioned from the cocoon, the metamorphosed mummy attempts to repress his possession by assuming new identities, disguising or concealing the face. A theft occurs. She creates decoys and doppelgangers of her own, imposing her fate or condition onto others. The mummy plots revenge against those ostensibly responsible for her possession.

Transmission: Optional stage. By uncovering her true uncanny face, the mummy can infect a new victim, renewing the cycle. This stage can include a period of disembodiment, during which the original mummy transmigrates to a new host. If transmission does not occur, the mummy dies and renews the cycle.

Death: The mummy dies, typically as the result of a fall, damage to the face, or less frequently by fire. After death, the cycle begins again, either with the victim if transmitted, or otherwise with oneself reborn. This death, too, is a fake death, for it only implies a renewal of the cycle.

———

Now to test our hypothesis. I haven’t yet mentioned Eyes Without a Face, Georges Franju’s 1960 horror film about an imperious surgeon crazed with guilt about mutilating his daughter Christiane’s face in a car accident. Dr. Genessier kidnaps pretty Parisians who resemble Christiane, removes their faces, and grafts them onto Christiane’s face. Try guessing his first victim’s name (remember, it’s set in Paris):

At the beginning of the movie, Christiane (played by Edith Scob ((Scob also appears in Holy Motors, which ends with Scob inexplicably donning a facemask and wandering off.))) is already in Imago, as she’s forced to wear an uncanny facemask, cast from Scob’s own face—like Billy Lo, she conceals her non-face behind a replica of the face of the actress who plays her. When she sneaks down to visit Edna Gruber, one of her father’s kidnapped victims, Christiane progresses to Transmission—she sees her own masked face in the mirror, removes the mask, then caresses Edna’s face. Edna passes from Infection (screaming at the sight of Christiane’s uncovered non-face) to Fake Death (she faints, is anesthetized and bound to the operating table). During her nauseating face-ectomy—way grosser than The Game of Death’s facial reconstruction scene—Dr. Genessier and his nurse accomplice wear surgical masks. Edna then awakens in Imago, with her face stolen and her head wrapped in bandages; she revenges herself by knocking out Dr. Genessier’s accomplice, and completes the cycle by leaping out a window, to her Death. Dr. Genessier stashes her body in Christiane’s fake grave.

Soon after the transplant, Dr. Genessier smugly tells Christiane, “Now you have your lovely face. Your real face.” We see the familiar dissonance: her face (which is also Scob’s real face) is not her real face at all, but that of a dead woman who resembles her. Christiane senses it too: “When I look in a mirror,” she replies, “I feel like I’m looking at someone who looks like me, but seems to come from the Beyond, from the Beyond…” As a fictional character, who else could Christiane be referring to but the actress who plays her, Edith Scob? For a fictional character, “the Beyond” is reality.

Christiane’s body rejects the face graft; meanwhile, the police become suspicious at the uncanny resemblances between the discovered victims, and (as in The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu) dispatch a decoy to Dr. Genessier’s office to ensnare him. The decoy is captured, but in the final scene, Christiane saves her, and releases Genessier’s laboratory doves and dogs, the latter of which tear Genessier’s face off. Christiane, with a dove perched on her arm, wanders off. Doves are homing pigeons, so if it’s guiding her anywhere, it’s probably returning somewhere it’s been before.

———

Some loose inferences about mummies:

—The beginning of the film doesn’t necessarily coincide with the beginning of the cycle.

—Stages can be brief or prolonged.

—Theft and trespass are recurring motifs: Billy Lo, Beatrix Kiddo, Quilty, Humbert, Edna Gruber, Trelkovsky, Fu Manchu, Imhotep, Nina Sayers, and Eric Draven either have important things stolen from them or orchestrate thefts themselves. And Billy Lo, Beatrix Kiddo, Quilty, Humbert, Trelkovsky, Fu Manchu, Imhotep, and Eric Draven all commit some B&E or inveigle themselves into someplace forbidden. Kidnapping is also common. These crimes are all built into the archetypal raid of the mummy’s tomb; with respect to identity, possession constitutes theft, trespass, and kidnapping.

—Not everyone who encounters the mummy becomes possessed. Victims are prone to identity crises: Bruce Lee, who wanted to show “the true Oriental” but was pressured to be “exotic”; Christiane, who lacks a face; uptight Nina, coerced into becoming more sexual; the multiply pseudonymed Beatrix Kiddo; Peter Sellers, claiming no personality of his own; Vladimir Nabokov, the perpetual exile. A hereditary component can be discerned in the lineages of Caines, Carradines, Lees, and Nabokovs, as well as Helen Grosvenor’s Egyptian parentage, the descendants in each case overshadowed by their precursors’ shades.

—The curse’s cyclical nature is betokened by annular objects: a shot of a roulette wheel introduces The Game of Death’s title sequence; a spiral staircase leads up to Trelkovsky’s room in The Tenant; Eric Draven fights to reclaim his wedding ring; The Mummy was based on the HG Wells story “The Ring of Thoth”; Freud exemplifies “The Ring of Polycrates” as uncanny ((The title alludes to a ring that Polycrates threw into the sea but returned to him in the body of a fish.)); Nathaniel in “The Sandman” seeks a ring to offer to Olympia; a mysterious millstone sits in Nayland Smith’s yard in The Fiendish Plot…; and then there’s The Ring and Circle of Iron.

—Mummy movies tend to be parts of series, sequences, or revivals: Polanski’s Apartment Trilogy, The Game of Death series and its imitators, Kung Fu, The Ring, the dozen-or-so installments of The Mummy, the half-dozen Fu Manchu films, Lolita and its remake, Kill Bill’s two volumes (with others possible), and so on.

—Mummies tend to have counterparts of the opposite sex: Billy Lo and Ann Miller, Eric Draven and Shelly Webster, Fu Manchu and Helen Rage, Imhotep and Helen Grosvenor, Humbert and Lolita, Quilty and Vivian, Beatrix and Bill, Christiane and Dr. Genessier. The actors who played them were all married.

———

More observations:

—Why are there no fatal falls in The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu, The Mummy, or Lolita? No shattered glass in Eyes Without a Face? Perhaps the template is flawed. Like Freud, “we must be prepared to admit that there are other elements besides those which we have so far laid down,” and that we’ve overlooked some denominators shared between mummies and the Uncanny.

One possible explanation is that some of the qualities transmitted from mummy to victim are not features of mummyism at all, but rather the transmitted characteristics of particular mummies; in other words, each host leaves the psychic residue of her own identity. It’s possible that the yellow tracksuit recurs in The Game of Death and Kill Bill not because they’re both mummies, but because the mummy Billy Lo transmitted it to Beatrix Kiddo (probably via David Carradine, or else Quentin Tarantino, who worked with Enter the Dragon actor John Saxon). The laws governing these hypothetical “paratransmissions” are not in this essay’s purview, though they may be covered in a sequel.

—Lee, Kubrick, Nabokov, Polanski, Tarantino ((In a 2009 interview, Tarantino claimed he isn’t religious but believes in “past lives.”)), and Humbert were all atheists. Many of the narratives concern tampering with the occult or playing God: Dr. Genessier, Imhotep, Fu Manchu, Top Dollar, and those seeking revenge (contra Romans 12:19). Our word for “uncanny” derives from the Scottish for occult. Linking mummyism to divine retribution seems reductive, but it’s telling that many religions promise a remission of the cycle of death and rebirth.

—Lee, Kubrick, Nabokov, Sellers, Dean Jagger, Caine, Bill, and Humbert were all killed by faulty circulation. Billy Lo, Trelkovsky, Dr. Land, Edna Gruber, Eric Draven, Nina Sayers, Top Dollar, Nathaniel in “The Sandman,” and The Mummy’s Ghost’s Yousef Bey fall to their deaths (as Natalie Portman was rumored to). Quilty and Genessier are killed by wounds to the face, as Billy Lo and Beatrix Kiddo are fake-killed. Are these just film tropes, or is it significant that falling, fire, and facial mutilation (loss of teeth, for example) are archetypal dreams?

—Counting bandages, many mummies wear white clothing, a color both vestal and deathly: Sadako’s nightgown, Christiane’s robe, Beatrix Kiddo’s wedding dress, Fu Manchu’s Elvis getup, Quilty’s bedsheet toga. (Occasionally those related to the mummies wear white: Steiner, Eric Draven’s girlfriend, Helen Grosvenor, etc.). Freud might say that these are not symbols but symbolic referents—in The Interpretation of Dreams he mumbles something about how ghosts symbolically correspond to “female persons in white nightgowns,” the mother coming in at night to comfort the child.

—Can the curse be stopped? Some films suggest a disruption to the cycle—Billy Lo, Imhotep, Quilty, and Christiane all seem to conclusively break free of their repeated experiences, either by dying or killing the apparent cause of the cycle. It can’t be proven, of course: the potential for resurrection is eternal, even for the unborn and unmade.

Still, that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. Mummies revive and possess others by exposure, so perhaps one should avoid being beheld. Maybe this explains the disguises. And maybe this is why Beatrix Kiddo plucks out the eye of her double, Elle Driver, or why The Crow’s Myca eats her victims’ eyes; why Freud says the uncanny effect in “The Sandman” is “directly attached… to the idea of being robbed of one’s eyes”; why David Carradine plays a blind wanderer in Circle of Iron (perhaps after studying under the blind Master Po in Kung Fu); why Lolita picks up a sculpture of a severed hand and uses it to idly poke at the eye of a severed head sculpture (Freud: “a severed head, a hand cut off at the wrist”); and inversely, why mummies have particularly intense eyes, usually exposed in spite of their wrappings, all eyes without a face. Hence the pan-cultural “evil eye,” or the status of eyes as the locus of identity, proverbial windows to the soul.

“Looking away shall be my only negation,” Nietzsche said in his discussion of eternal return. This raises the final question of whether one should necessarily want to end the mummy’s curse. Some, like Eric Draven and Trelkovsky, loathe their condition and act out by shattering mirrors, attempting suicide, etc. But it suits Fu Manchu and Imhotep fine. To be fated to a particular doom, or doomed to a fate, is not necessarily tragic. Mummies may be advised to take an attitude of amor fati.

Face Foreword

If I understand the character of the game aright, I might say, then this isn’t an essential part of it. (Meaning is a physiognomy.) —Ludwig Wittgenstein

I know I’m cursed because I’ve returned. I exhibit mummylike symptoms. The novel I’m working on, unwillingly sidelined while this essay was written, features a female character in a hospital bed, wrapped in bandages and missing a tooth after a severe accident, who’s visited by an Asian male, who later winds up with his face mutilated. I suppose anyone reading this essay would also be exposed to the curse.

Consider the name of The Game of Death. Neither Bruce Lee’s original project nor the final product had anything to do with games. Games are abstract, constructed metaphorical systems bound by rules, experiences that are also doppelgangers of experience. The Game of Death is a fake death, but the death of what? And for whom is The Game of Death a game?

Many of the issues we’ve discussed appear in Wittgenstein’s posthumous writings, like his notion of “family resemblance” (which resembles our idea of paratransmission), or his famous analogy between language and games, but maybe nowhere more than in the regard of the face, his incessant analogies between faces and intrinsic meaning—“The face is the soul of the body,” he wrote.

In “Wittgenstein on the Face of a Work of Art,” Bernie Rhie describes how Wittgenstein not only argues that the human face is the manifestation of feeling itself (rather than a medium through which obscure Cartesian inner states are conveyed), but attributes faces even to “words, games, and melodies.” Wittgenstein writes that a familiar word becomes the “likeness” of its meaning, and that “in the use of a word we see a physiognomy,” and finally declares outright, “meaning is a physiognomy.” Rhie also indicates how philosophers like Adorno, Benjamin, Deleuze, et cetera have also relied on face metaphors and images to discuss meaning and expression. There’s something distinctively postmodern to making games of altering, concealing, disfiguring, and destroying faces.

The postmodern era has seen two high-profile deaths—the author and the subject. Postmodernism is the name we might give to the game of death: to deconstruct is to kill, to read is to raid the crypt (to decrypt), and to behold (to be bound) is to resurrect (to possess and be possessed).

Acknowledgements

This essay recklessly plundered the tombs of other writings. Bennett Sims’s ((Bennett Sims is, coincidentally, the name of the Warner Bros. executive who greenlit Kung Fu.)) “White Dialogues” provided, among other ideas, the concept of films as pyramids full of mummies (itself drawn from André Bazin) and the idea of secret continuities between apparently unrelated films (resurrected from Jalal Toufic). Credit goes to Ben Mauk for directing me to Bruce Lee’s cameo in The Tenant and Rebekah Frumkin for her thoughts on Wittgenstein.