“I must confess I have enjoyed nothing. I have been bored my entire life.”

—Lawrence Durrell

Early last year I found myself standing inside Strand bookstore, an entire city block of new, vintage and rare books, and one of the major points of light on New York City’s literary event circuit. Authors gather there for readings, signings, and book releases, and on any day of the week the many floors are overflowing with customers, readers, and tourists. I regularly stopped by, as I’m sure all recent clingers-on to the New York literary community do, to spend an hour or two after work thoroughly rifling through the well-kept sections dedicated to my favourite authors, and daydreaming over the rare first printings of my favourite novels. They have the first edition of East of Eden, The Sun Also Rises, and other cornerstones of American literature behind glass cases, available only to the true connoisseur. The Strand is every bibliophile’s dream. But, on this specific day I was not at the Strand to buy books; I was at the Strand to sell books.

Walking towards the book buyer’s room with two fifty-pound backpacks strapped across my shoulders, I was hopeful I could at least sell half of my lot. I had recently transported my home library from Canada to my apartment in Brooklyn, a task which took more time and money than I foolishly expected it would. And unfortunately, an average income apartment in Brooklyn is a lot smaller and more expensive than those in my hometown, and so I was left with the sad task of having to offload some of the chaff (chaff, in this case, being around twenty-five pristine literary classics) due to space considerations. That and one of the most expensive cities on the planet had certainly lived up to its reputation, and I was practically hemorrhaging money. So the books had to go, and after an afternoon of standing in tightly packed trains and trudging down Broadway, I was just about ready to never see any of them again. Panting in the wet July heat, I began to unpack the books from my bags and place them on the table for appraisal, one by one, all very heavy, all very thick. I am not a strong man.

I confess that I tie up a lot of my personal identity in the books that I own. It’s silly, yes, that so much of my psychic energy is wrapped up in paper, but I’m like a lot of young literary people: I like a nice bookshelf. So it was truly cringe-worthy that I was forced to sell these books, some with new designs and in fine new printing, but it had to be done. I definitely wasn’t carrying them back to Brooklyn. New, these books would be worth between twenty and thirty dollars, and I had hoped that I could get around half of that for each. After all, I knew that condition always played a part in these negotiations, and all were top-notch, with not a single folded page. I was wrong.

“We only pay one dollar for used paperback fiction,” the clerk said. “And this is used paperback fiction, even if it’s all in good condition. We only have so much room, you know.”

I balked. One dollar for Fathers and Sons? One dollar for The Waves?

“Sorry man, it’s store policy,” the clerk said. “I can only give you like fifty bucks. We already have a few copies of these, so some of them are going to have to go on the racks outside.”

The Strand keeps some of their used books in bins outside of the store along Broadway. If the books weren’t damaged now, they soon would be. I bristled with anger and frustration. I was surprised that my beloved novels were worthless. I think the clerk decided that I was likely hard up for train fare and desperate for cash. He began to count them up.

“So, we’ll take all of these. Except, uh…” he said as he slid the Quintet back across the table. “Not Durrell. We haven’t really sold anything of his in a long time.”

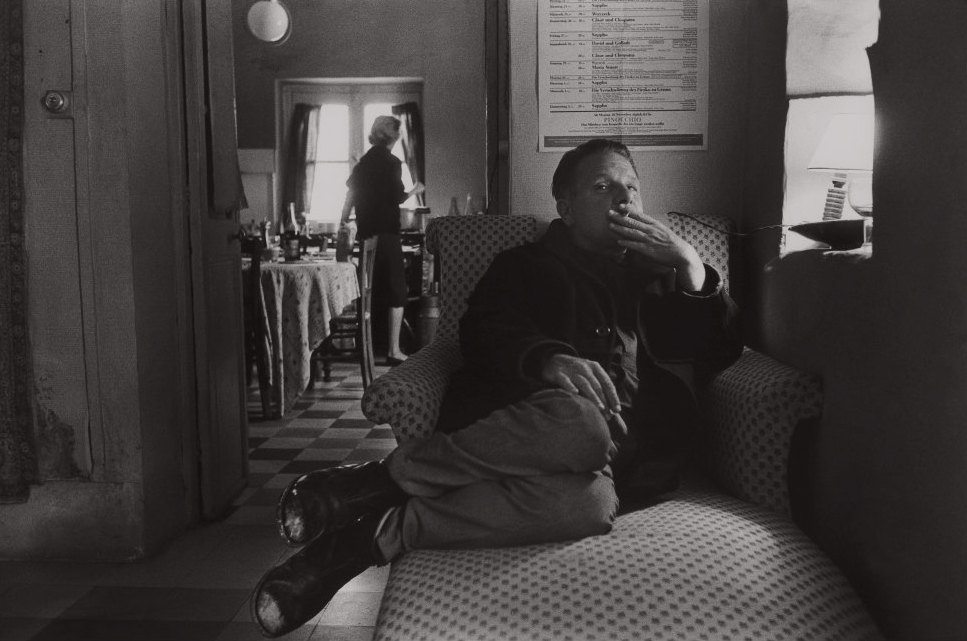

As he announced on television in 1986, four years before his death, and the year of my birth, Lawrence Durrell was bored. In ‘86 he was already seventy-six years old, and had written over a dozen major works, including novels, travel literature, poetry, and theatre. He was a towering figure in the austere post-war literary climate of Europe, a champion of experimental prose and poetics, a modern master. He had seen a lot in his life: he had married four times, but watched every one of his wives die, either slowly from mental illness or other diseases, or in one tragic case, a suicide. He had a daughter, but she committed suicide as well in her early thirties. He had lived in and around some of the most awe inspiring cultural centres of the ancient Mediterranean world— Athens, Alexandria, Rhodes, Corfu, Serbia, Cyprus, and perhaps foremost, Avignon, but then watched as the military and financial conflicts of the last great century saw them all destroyed or fade into obscurity. I imagine him, a very old man in the late 80s, still waiting for the other shoe to drop, for some kind of last laugh, for some kind of final, lasting literary acclaim.

But that never happened. The last train never came in—Lawrence Durrell died, largely unnoticed by the literary world, in 1990.

And now, in 2014, Durrell has failed to be appreciated in any substantial way by modern audiences. In fact, the opposite is true: he is positively derided in most serious literary circles, and his books are rarely studied in universities. His novels are said to be antiquated and selfish, indulgent and over-written. His prose, once thought to be incisive and muscular, is now judged as florid and confusing. His cipher-like complexities have been have been set aside with a shrug. During my stint working in the literary industry in New York, few of my peers, people within five years of my age, had even heard of Durrell, or if they had, remembered his books as overly verbose bricks they had assigned themselves out of guilt. And yet, sixty years ago, few people doubted that the books of The Alexandria Quartet, Durrell’s first serious set of novels, were the literary achievements of their age, and would undoubtedly win him the Nobel Prize. But they didn’t. And nowadays, they are little more than a strange literary oddity.

In the 1961 Nobel deliberations, Durrell didn’t even make the final lightning round. In ’62 however, he was given some consideration. Along with Robert Graves and French dramatic Jean Anouilh, he made the shortlist for the prize, but ultimately lost out to that great, although sometimes shrill voice of America, John Steinbeck.

When one examines the reasoning behind the committee’s decision, it appears that Steinbeck’s citation arose largely from extra-literary considerations and lethargy. From the recently declassified archives in Sweden (Nobel nominations are considered top secret for an incubation period of fifty years), we learn that ’62 was a standstill year for the Swedish academy. As a member reported, “There aren’t any obvious candidates for the Nobel Prize, and the committee is in an unenviable position.” Steinbeck was apparently the lowest of all the hanging fruit. One wonders why the committee had nominated him a previous eight times if he was indeed a mollifying choice.

Jean Anouilh suffered from simply being French. The poet-diplomat Saint-John Perse had won in 1960 and it was decided that awarding the prize to another French citizen would be bad form. And Sartre was on the rise, sure to take it home soon.

Ezra Pound damned Graves. Graves was ultimately decided to be poet rather than a novelist—a line which, nowadays, is often crossed without reproach. And because he shared the poetic limelight with the still-clinging-to-life Pound, an undeniable master, he was overshadowed. Pound’s skill as a poet was considered unparalleled by the committee, and it was decided that as long as he remained alive, no other poet could claim the prize. Pound was never chosen due to his politics, likely a decision by the committee to attempt to erode his future impact in the canon, and sideline him for more socially acceptable, less insane artists. If Graves were awarded the prize that year, I imagine an asterisk next to his name on the plaque with the subtext “Best Poet in the World Who Isn’t a Fascist.” The Nobel and other prestigious awards often contribute considerably to lasting acclaim. But award committees are subject to trending literary climates, nationalities, and politics—this was certainly the case in ’62, and is surely the case still.

In a deadlocked year, it’s easy to imagine the committee would opt for a safe bet, and not want to err on the side of an experimental newcomer in Durrell. For a body so focused on posterity, the Swedish academy would be sensitive to what might one day be seen as a misstep. Officially, Durrell wasn’t given the nod because the committee wanted more time to see his catalogue develop. The committee, however, also noted that his work “gives a dubious aftertaste… because of [his] monomaniacal preoccupation with erotic complications.” The problem for Durrell was that he never got another look. After ’62, no more nominations came in. His next series of novels, The Avignon Quintet, passed without much critical notice. But if for no other reason than Nobel or Pulitzer Prize winners get a special designation in their section at used book stores, and their books are generally reprinted multiple times, I regret that Durrell missed his chance.

Lawrence Durrell is my favourite author. I own every book he’s ever written in every imaginable literary form, including a few first printings. If someone published his tax records, I would probably buy those too. So it struck me personally that the clerk at the Strand would not even offer me a dollar for my copy of The Avignon Quintet, a series of novels that are, in my mind, without equal. Durrell’s books are very difficult to understand, and to even read, and for this reason he is understudied and under-read. But as I stood in the back of the bookseller’s room at the Strand, I wondered about written word itself, or specifically the written word which is printed in a physical book, which in the millennial era of Kindles and iPads is becoming steadily less valued, or in Durrell’s case, apparently literally worthless. I wondered about posterity. How can a person spend a life in austere artistic toil, but be lucky to wind up in a rack on Broadway?

I believe that the main reason Durrell has fallen out of favour with contemporary audiences is that he doesn’t really have an oeuvre. Steinbeck’s novels, in contrast, are mainly concerned with rural American hardships in the dog days of the depression, and are populated by generally honest folks just trying to find their place in the great American dream: an enduring motif if there ever was one, fit to be studied ad nauseam in prep schools and universities. Durrell’s novels, of which there are more than a dozen, share no common figure, treatment, or theme (despite perhaps, their “erotic complications”), and often are occupied with topics outside the pertinence of the high school classroom. Of course, many authors have endured along with their risqué or erudite tropes, but none who have so readily shirked the confines of a national identity, linear narrative, or ability to be brief. Durrell’s books are also very long.

However, it is my opinion that Durrell’s works, although experimental and somewhat radical for his time, are long overdue for another reading, and are slightly less insane than often made out to be. Despite his complexity, Durrell manages to communicate with us clearly, although circuitously, and largely without the overwhelming literary affectation of various experimental authors writing today, authors who, now much beloved by the established literary community, stand on his shoulders. Metafiction is now generally an acceptable mode in modern literature, if the enduring success of Murakami, Coetzee, and even to some extent the poetry of Lydia Davis can be trusted.

A closer reading of Durrell will show that experimental fiction is something he was doing very well sixty years ago, and because of this he deserves at least a nod of recognition from that section of the contemporary literary audience who appreciate a deep, layered novel. “Layered” is a term often bandied around by critics describing authors writing about authors, but in Durrell’s cause, the authorship of his books are actually disputed by characters within his books, adding another layer to the strata. For this reason, Durrell requires a lot of patience. I understand that patience is something which seems to be in short supply from a lot of people in my generation, especially when understanding is in doubt. But with enough patience, Durrell is an enjoyable puzzle. Below, I offer a detailed introduction to the Quintet as an effort to tempt the reader. It may seem like I’m spoiling the plot, but rather I’m providing a table of contents. The novels of the Quintet can be read in any order.

The first book of The Avignon Quintet, in my opinion Durrell’s most important work, is called Monsieur, or The Prince of Darkness. The novel is written from five different perspectives and claims to be written by five different people, four of whom have not ever, to my knowledge, existed: the first person is Lawrence Durrell (who definitely existed) the author, also referred to as D in the novel, and who sometimes refers to himself as the Devil in the Details, or ‘a devil’, and is referred to as such by numerous others in the book, often equating him with the “Prince” of darkness himself. However, Durrell is physically writing the book in real life as the story unfolds and he never denies this. The book says his name on the front. His face is on the back. He has a mailing address, drives a car, and shaves every morning. He is as real as anything else is real.

Second, the novel claims to be wholly invented by a character within the novel who doesn’t make his appearance until the crucial last fifty pages once he finally wrestles the narrative from Durrell: the fictional author Aubrey Blanford. Earlier in the narrative, Blanford is mentioned to have recently finished writing a novel, and is now famous after its widespread appeal. Blanford contends that the very book Durrell claims to have written, and the one the reader is currently holding, Monsieur, or The Prince of Darkness, Blanford actually wrote himself. And he has proof. He also has a mailing address and shaves his (fictional) face every morning. He is conscious of Durrell, and is constantly quarrelling with him over who invented who first.

Third is Robin Sutcliffe, a character in Blanford’s novel, solely created by Blanford and who admits to this, but who will regularly call Blanford up on the telephone from time to time to ask for writing advice. Blanford is known to be very old, and perhaps a bit addled, but a great writer. Sutcliffe is writing the same novel as Blanford and Durrell, and although it is the same book word for word, Sutcliffe calls it by another name, just The Prince of Darkness, to distinguish it from the two.

The crucial difference between Sufcliffe and Blanford is that Sutcliffe knows that he is unfortunately a figment of Blanford’s imagination, whereas Blanford readily denies the fact that he is a figment of Durrell’s. Sutcliffe is a sympathetic character: it bothers him a great deal that he actually doesn’t exist, and he’s often rather depressed. But by writing the same book as Blanford, and simply changing the title, Sutcliffe is vying for, in spite of the overwhelming limitation of not technically existing, something to extricate himself. There is a particularly jarring scene where Sutcliffe calls Blanford up and berates him for being completely insane because he’s talking to Sutcliffe in the first place.

Fourth is Bruce Drexel, the protagonist, and the person who narrates most of the novel. Bruce actually writes most of the novel, or at least he dictates it to be written, because Bruce’s notes and diaries allegedly comprise the bulk of the text. Of all the characters, he does the most “writing.” Bruce is acquainted with Sutcliffe, whom he knows to be a great author, and he’s vaguely aware that Sutcliffe is trying to write a novel based on Bruce’s life. Bruce believes that he himself is as real as Durrell, although he knows a fictionalized version of himself is being interpreted in an upcoming novel by his friend Sutcliffe. But that doesn’t bother him. After all, Bruce is a man who goes about the world and does all kinds of interesting things. He’s a diplomat and press attaché for the government (Durrell’s old job: in many ways, Bruce is Durrell). It doesn’t strike Bruce as odd that Sutcliffe is writing a novel in which Bruce is the sole character, because Bruce believes that’s something Sutcliffe would do. Bruce does not know, however, that Sutcliffe is a fictional creation of Blanford. In fact, if that is true, Bruce would also be a fictional creation of Blanford because he lives in Sutcliffe’s world. But Bruce never meets Blanford, he only hears of him as a distant friend of Sutcliffe.

Fifth (and yes, there are five for a reason, this is a quintet after all) and final, is Piers de Nogaret, the only character in the book who actually might be “real” insofar as something happens to him outside of the loop of “fiction”: he dies on the first page. Later, when the body is removed, Bruce finds a secret manuscript hidden by Piers’ in the dead man’s hotel room. Bruce then begins to write a novel based on this manuscript. The manuscript is of course the incomplete novel, written by none other than Piers de Nogaret himself, and unfinished due to his apparent suicide: Monsieur, or the Prince of Darkness.

In addition, and this is somewhat difficult to believe, all of the alleged writers of the book were at one time members of a secretive and bizarre Gnostic cult. This cult believed that when Christ was resurrected he was in fact resurrected not by God, but by the Devil, and that this is the main source of all evil in the universe. Because of this belief, this wholly undermining aspect of the universe, the presumption of this cult is that humanity’s situation is now absolutely unsolvable, and, chillingly: the only sensible reaction to being alive is suicide. This explains why all the characters in the book die off one by one, in “apparent” suicides. They’re looking for a way out of the universe. This also glimpses into Durrell’s past, commenting on the suicides of his wife and daughter, and perhaps, sadly, of Durrell himself.

There are four more books in the series, each as complex and exciting as the first. In the final novel, Quinx, Durrell ties everything up in one brilliant masterstroke. One of last chapters of the last book in the Quintet, the last series that Durrell wrote before his death, is entitled, fittingly, The Prince Returns.

Durrell is complicated, and he does go on a little too long. Even if I’ve managed to do a decent job in summarizing the first book of the Quintet, it’s still very much a challenge to read. But in my opinion, a worth-while challenge, one that awards the reader with a novel that can be studied and re-read many times: a novel that deserves a place in the canon. It is a novel uniquely positioned in opposition to the current trend of bloated, post-modern novels about nothing, to deliver some much needed insight into the mirage-like layers of reality in our new century.

By naming himself as a character in his fiction, Durrell became, in a way, fictional himself. A character stuck in a time forgotten. But in the digital world of the self detached from its surroundings, the subject detached from the object, his study of the tension between the real and the unreal can help bring us back to reality. Durrell wasn’t insane, he was prescient.

I never did sell any of my books at the Strand. I hauled them all back to my small apartment in Brooklyn, stacked them up under my sink, and found a third job. Most of them are still there, waiting to be shipped home. But not Durrell. His books returned with me.

What will be his legacy?

“When I leave I usually go to the station on my way home and wait for the last train to come in from Paris. There is never anyone on it I know—how could there be? Often it is completely empty. But I walk about the town at night with a sort of numbness, looking keenly about me, as if for a friend.”

—Lawrence Durrell