A friend of mine recently got himself a “grown-up” job. He went, in a matter of weeks, from a broke, struggling artist, to someone with a 9 to 5 and a retirement fund. I’m happy for him, and he’s thrilled, but the hours are long. He told me that, recently, he left the office at 1 a.m.!

But the other day, while rushing to meet a freelance illustration deadline, I thought about how frequently I work into the wee morning hours to meet deadlines, or finish layouts, or squeeze in some time working on long-form book projects. Being a cartoonist and freelancer means I often work at home until I go to bed, whenever that may be. It’s not unusual to put in around twelve hours of work in a single day. (At my daydreamiest I think about what I’d be making if my freelance comics job was compensated at an hourly rate.) If the seriousness of a job is measured by the hours worked, why are some of the creative professions still not considered work fit for “an adult”?

When considering how society sees adulthood through the lens of employment, so much is measured monetarily. With increasing wage gaps, imbalanced pay scales (for teachers versus investment bankers, for example), and widespread unemployment, perhaps it’s a good time to reevaluate the belief that “being an adult” equals “making lots of money.”

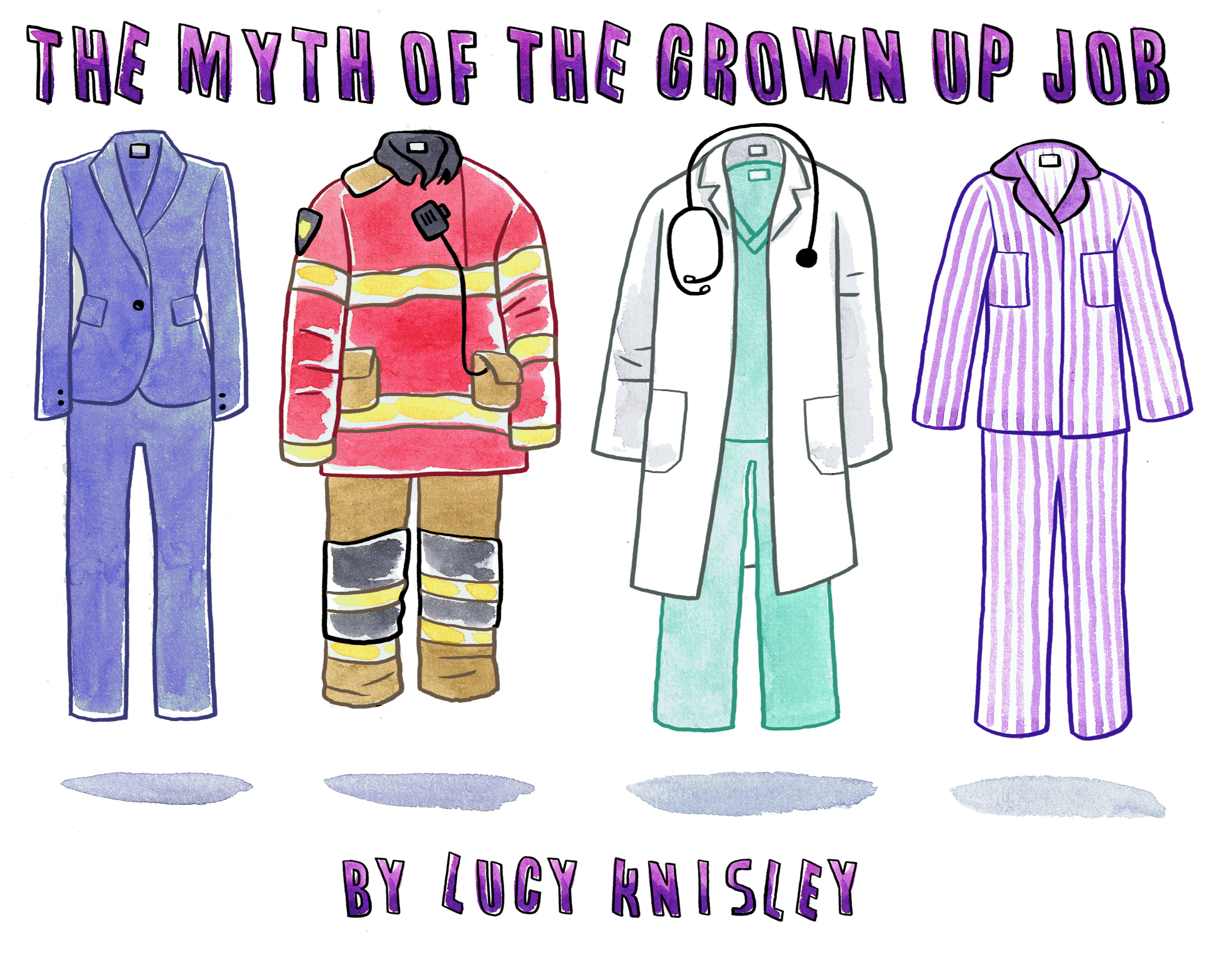

I suppose some might measure adult employment by whether or not you have to take your pjs off to go to work. Thankfully, I do not.

As a child visiting my dad’s work, I was horrified by the 90s-style cubicles, the water coolers, the conversations over the copier. Now, from time to time, I romanticize it a little. It might be nice to work around other people. Working from home on a long project all week can make a person a little loopy when it comes time to return to civilization. There are, of course, comic artists who band together to rent a studio; just take Periscope Studio in Portland, where workspace, advice, facilities, and clients are all communal. I’m happy working from home, but it can hurt my case when people catch me in my studio at 3 p.m. in my pjs. (Perhaps investing in a more formal pair, something business casual, would be beneficial.)

Of course, this is all subjective. Everyone has his or her own individual criteria determining who qualifies as an adult and whether or not that title is appropriate yet. It’s all in how you measure “it” (whatever “it” really is) in yourself. But it can be enlightening to examine how it is measured from an outside standard.

People often assume I always wanted to be a cartoonist, that being a cartoonist was a childhood dream carried over into adulthood with the help of a childlike vision. But no, I wanted to be a doctor until I was about eleven. It was only after I realized that most of my classmates had ceased to lose themselves in drawing the way they used to that I thought making art and telling stories might be something I was more cut out to do. That, and I was a terrible biology student—scientific diagram assignments aside.

Because some people mistakenly tie comics to children’s entertainment exclusively, they deduce that I must be a child, or at least more childlike than “adult-like.” Of course, retaining a level of innocence can be advantageous within a variety of creative professions, but most of my work is geared toward adults. I go to meetings, take business calls, sign documents, go to conferences, consult with peers, and fill out invoices at my job. It can be serious and difficult and stressful, but the end result is a funny book.

I make about the starting salary of a teacher, and essentially do what an author does. I work on commission for clients like a journalist would, and hawk my own merchandise like a bookseller. But something about the title “cartoonist” tends to make people say, “Aha! Here is someone who never grew up!”

It’s nice to remind those pitying dinner party guests (and myself) that I make something that people want. Even in this flailing economy, the creative professions haven’t really suffered all that much compared to other industries. Sure, book sales are lagging, but they sort of always have. Artists will always struggle. At least we’re used to it. At least I don’t make cars (a very grown-up job).

For twenty-seven, I look fairly young (the genes, thanks); I still get carded and receive the occasional under-eighteen discount. So it was not a surprise when a gentleman on a train inquired as to what I wanted to do when I grew up. When I replied, “make comics,” he got sympathetic and wise, informing me that it’s a real “man’s job.” At least he regarded the difficulties (financial and time-wise) of working in a competitive creative industry as challenging enough to only be faced by an adult. Leaving aside the inherent sexism of his comment, it was clear that he felt sorry for me.

He shouldn’t have. I love my work, and I take great satisfaction in making it. I also take satisfaction in the balancing act of demanding fair pay, eking out a reasonable contract, and learning more about the business aspects of creative industries.

Smart artists know to defend themselves and their right to fair pay. It’s important for these artists to stand up for what they want, and what they do. Part of that is forcing people to understand that a creative profession does not exile you to the fringes of society. Being covered in ink might damage your credibility, but it’s not quite the same as being a child covered in finger paint.

We’re lucky to have some help. Katie Lane is a lawyer who specializes in freelancers and artists, and keeps a blog, Work Made For Hire, about rights and legal issues pertaining to freelancers. She and others like her have been a serious aid to cartoonists like me, helping us navigate the pitfalls of working for clients, and setting down a path so that we can begin to make headway in being considered respected (and adult) professionals. Freelancers unions and illustrators’ guilds help carve out ways to get medical care and retirement benefits (another mark of adulthood), while freelancing agents help to clear the way through paperwork so that artists can focus on work instead of finding it and negotiating it.

But despite all of this, artists are still often seen as childlike. Is it because children are encouraged to draw freely, while adults aren’t? I defy you to engage in a long, boring phone conversation and keep that message pad free of marks, then tell me that art isn’t intrinsic to human nature, and therefore meaningful. Not the best argument ever put forth, but I stand by my “phone pad” theory.

The bitter upside to the self-perpetuating low pay in many creative fields is that most artists (myself included) are taught that being an artist requires low financial expectations. We expect to struggle, just as we expect to strive for better pay and be respected as adults. Most of us are braced for this fight when it comes. Many of us balance other jobs—like my friend with the brand new 401(k) who now has to squeeze in drawing on the subway ride home from work—in order to support our art.

But while friends growing up thought about their adult lives with fancy houses or cars, I tended to imagine a book with my name on it, a show of my work in a gallery. I’ve had both of those things, neither of which came with much dough, but many of my friends are still working toward their cars and houses. I’m not saying you should set the bar low; I’m saying, artists sometimes have different career goals. Maybe that’s what makes us seem slightly less adult than others in non-creative industries.

Sure, it’d be nice to make more than what works out to be around $3 per hour, and to have a job that I can mention at a dinner party without being condescended to. But at least I don’t have to be out of the house, in uncomfortable clothes, somewhere I hate by 9 a.m.. After all, I haven’t had to do that since I was a kid.