The following introductory essay, as well as the two poems that follow it, has been drawn from “The Insurrectionary Turn,” a portfolio of new political poetry curated by Joshua Clover, which appears in the November print of The American Reader.

The Insurrectionary Turn

by Joshua Clover

A nineteenth-century British, twentieth-century West Indian, or a twenty-first-century Chilean poet would be confounded to hear that recent U.S. poetry has been wearing its politics on its sleeve overmuch. And yet that very allegation pervades American culture. Sometimes it arrives as a more-or-less sophisticated case for the autonomy of art: for preserving an undistricted space of imagination that is thereby one of political possibility. Sometimes it is little more than bourgeois ressentiment, an attempt to turn the truth of the era’s political closure into a desirable aesthetic. You would think that the last three or four decades of American poetry were mired in a dull political didacticism against which we needed to be defended. In truth, said poetry (of the published and sanctioned kind) has pursued almost anything else, with historic zeal. Every poet claims a politics; political content, not so much.

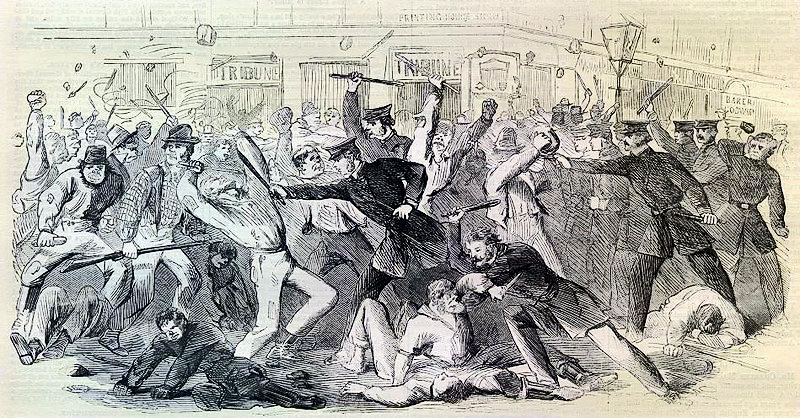

The last year or two has seen certain changes. These developments signal the preconditions for, rather than the flourishing of, political poetry. I can speak of but a few places in general, and with any great intimacy only about the Bay Area: in these places there has been a striking leap of poets into direct political antagonism. Here I do not mean the taking up of political questions, but the taking up by poets of political tasks in the face of an intolerable situation, and the practical work of burning it down. I have seen nothing like it domestically for a good while; the only quasi-cognate is the broad entanglement of poets with the New Social Movements in and around the Seventies. (Writing this, how keenly I miss Adrienne Rich!)

Rather than the complex and current-crossed identitarian wave that crested in that moment, we have in our own a set of struggles articulated more particularly (but not exclusively) around anti-capitalist and anti-statist analyses. This is not so surprising in the midst of the perplexing and briefly optimistic apparition known as the Occupy movement. But that too is as much consequence as cause; the shift seemed to start before Zucotti Park’s encampment. We might name instead the global economic catastrophe which has delivered to the economic core and its poetry-consuming classes a taste of the precarity and misery familiar enough elsewhere. “This is the age of throwing down,” some poet said outside an Oakland bar last fall, between tear gas and rubber bullets.

Chris Nealon, a brilliant poet and scholar, has captured this complicated and uneven shift most eloquently in his masterwork “The Dial,” which I would include here if I could. A brief fraction will have to do:

…let me mention what my friends were up against

First: other poets

the ones who’ve always said it was arrogant to have a politics

the ones who worry that we’re going to spoil the last untainted thing

Then: the police—bearing down on them on campus—later massed against them in

the squares—

Finally capital—unconcerned with poetry—at least as long as poetry never became a

metaphor for fighting back—

If this is one poetic registration of a sea change, another came from an unexpected quarter and epoch. In 2010 and 2011, the United Kingdom was buffeted by a series of riotous confrontations, in many regards distinct, but conjoined in their antagonism to heavy austerity in all its classed, raced, and gendered brutality. And for an odd, suspended moment, Percy Shelley was a pop icon: a stanza of his was cited again and again, inflected with admiration and admonishment, and some fear and much dark joy:

Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number —

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you—

Ye are many—they are few.

This was not a spectre anyone had expected two or five years earlier. Shelley’s return—under cover not of “Ozymandias” or “Mont Blanc” but “The Mask of Anarchy”—exposes something crucial, but only something, about our moment. The poetry selected here comes from within this exposure, this opening, this Insurrectionary Turn. It is not clear, to state the obvious, who will be this moment’s Shelley or Césaire or Cecilia Vicuña. It is not clear if there will be one, or eleven dozen, or none. Or if such a thing is desirable. But it is clear that such things are a possibility again, which is to say: we live in interesting times.

✖

[First poem: “RE: FWD: IS THIS LIST STILL ACTIVE”, by David Lau] >>