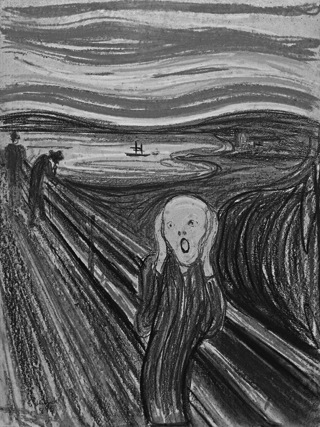

Edvard Munch’s “The Scream”. Photo Credit: Sotheby’s.

“[Painting] does not have to be ‘literary’– an invective which many people use in regard to paintings that do not depict apples on a tablecloth or a broken violin.” –Edvard Munch, 1929

Starting October 24, the Museum of Modern Art will open a six-month exhibition of Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Mostly because of its record selling price–close to $120 million– at Sotheby’s this past May, the work has been receiving the giddy attention of newspapers and magazines that don’t usually consider art exhibits to be a headline. In the online comments on these articles, there has been the usual outpouring of arousal and disgust that attends the expenditure of large sums on art (the routine spending of such sums on movies or political campaigns no longer fazes).

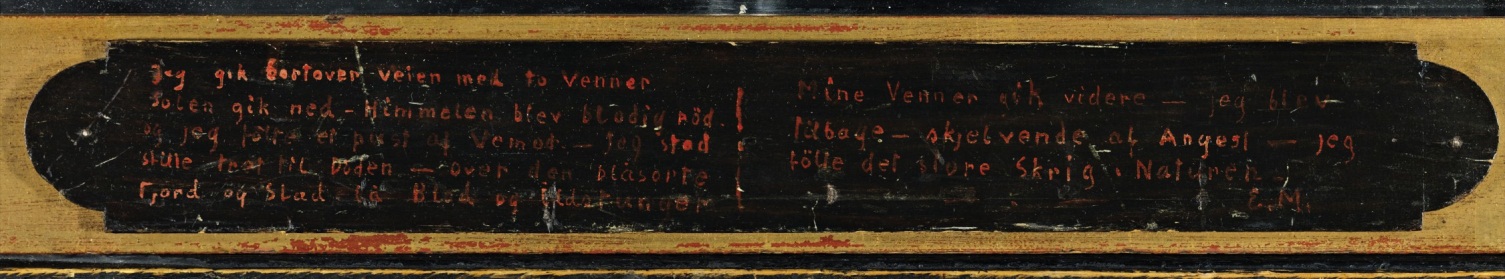

There are four versions of The Scream, not counting the lithographs. The version to be shown at MoMA is a pastel-on-cardboard from 1895. It is the only version executed in pastel, and the only version with a stooping figure in the background. It has one other striking peculiarity: the self-authored poem that Munch painted onto the frame, describing the experience that prompted the work.

There has always been an active conversation between art and poetry: ekphrastic poetry goes back to antiquity, and many images claim poetry as a source or influence. Painter-poets are numerous, too; William Blake even illustrated his own poems. But this version of The Scream is a singular instance of a modern painter bringing a poem he wrote into direct physical relationship with his artwork.

To fit the space at the bottom of the frame while preserving his line breaks, Munch recorded the poem in two columns separated by a vertical line:

I was walking along the road with two friends

The Sun was setting – the Sky turned blood-red.

And I felt a wave of Sadness – I paused

tired to Death – Above the blue-black

Fjord and City Blood and Flaming tongues hovered

My friends walked on – I stayed

behind – quaking with Angst – I

felt the great Scream in Nature

There is a childish poignancy to Munch’s neat hand-printed letters, the slight downward slant of the lines, the initials “EM” signed at the bottom– giving the poem a deeply personal feel. This seems to be what Munch intended. He once described art as the “soul’s diary,” and as many of the recent news articles about The Scream have noted, this poem stems directly from an entry in Munch’s diary.

But it isn’t identical. This is the 1892 diary entry from which the poem originated:

I was walking along the road with two friends

– the sun was setting

– I felt a wave of sadness–

– the Sky suddenly turned blood-red

I stopped, leaned against the fence

Tired to death– looked out over

The flaming clouds like blood and swords

–The blue-black fjord and city–

–My friends walked on– I stood

there quaking with angst– and I

felt as though a vast, endless

Scream passed through nature

In transferring the poem from the diary page to the frame, Munch refined it in small but important ways. The poem on the frame of The Scream bears no mention of leaning against a fence, as the diary entry does. In the diary entry, the sky turns blood red after Munch’s “wave of sadness,” but the poem on the frame reverses that order of events, saying instead, “the Sky turned blood-red./And I felt a wave of Sadness…” There is also a marked difference in the final lines. “I/felt as though a vast, endless/Scream passed through nature,” Munch wrote in his diary. But the poem he painted on the frame of The Scream dissolves this simile, and substitutes something altogether more direct: “I/felt the great Scream in Nature”. The revision is a rare linguistic example of the goal that drove all of Munch’s expressionist works: the starkest possible crystallization of emotional experience.