In Robert Burton’s mammoth 1621 The Anatomy of Melancholy, a meandering discourse on soul-sickness, Burton treats melancholy as a universal phenomenon, endemic to the human condition: “Kingdoms and provinces are melancholy, cities and families, all creatures, vegetable, sensible, and rational—that all sorts, sects, ages, conditions, are out of tune… For indeed who is not a fool, melancholy, mad?”

But nothing evokes melancholy like cities do. The countryside may have its Romantics—its Byrons and its Schillers, its Coleridges and its Shelleys—to identify the epic struggles of nature with the most magnificent dramas of the human soul. But the melancholics, concerned with neither high tragedy nor ecstatic delight but rather, to quote Burton, moods “dull, sad, sour, lumpish, ill-disposed, solitary,” are urban writers. The literary experience of urban space is so often the experience of longing, of nostalgia, of alienation, and of loss. For such writers, the city is not merely setting but allegory: a physical embodiment of the irrepeatibility of experience and the inevitability of decay.

Nearly every historic city has its brand of melancholy indelibly associated with it—each variety linked to the scars the city bears. Lisbon has its saudade: a feeling of aimless loss tied to the city’s legacy of vanishing seafarers, explorers shipwrecked in search of Western horizons. Istanbul has huzun: a religiously-tinged brand of melancholy rooted in the city’s nostalgia for its glorious past. As Orhan Pamuk writes, “the people of Istanbul simply carry on with their lives amidst the ruins… these ruins are reminders that the present city is so poor and confused that it can never again dream of rising to its former heights of wealth, power and culture.”

In each case, melancholy creates a psychic geography shaped by street-names: the presence of historic avenues, archways, back-alleys doubling as manifestations of absence. The self that wanders through the melancholy city bears the weight of that city’s history: the urban body the point of convergence for the imminent present and the past that no longer exists.

Such weight suffuses the work of one of the earliest urban melancholics, Parisian Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire is the paradigmatic 19th-century flaneur: the idling urban people-watcher, strolling or sitting in cafés on one of the city’s newly built grands boulevards, and fascinated with the workings of the recently-industrialized Paris changing all around him. Baudelaire was aware of urbanization’s cost: the sense of alienation from brethren who exist in such close proximity, and at such psychic distance. This Paris, after all, is a city of strangers, in which—as in the poem “To a Passerby”—two people can share a glance, share a brief connection, and then vanish from one another in a crowd, to be reunited only in the afterlife:

Elsewhere, far, far from here! too late! never perhaps!

For I know not where you fled, you know not where I go,

O you whom I would have loved, O you who knew it!

The crowd moves, the moment cannot be repeated, the potential lover can never be found again.

At the core of such alienation is the temporal disconnect encoded in the architecture of the city-scape itself. The vanished old Paris is still present alongside the new: that presence—a reminder that the was no longer is, stirs Baudelaire’s existential despair. Thus Baudelaire’s “The Swan”:

— Old Paris is no more (the form of a city

Changes more quickly, alas! than the human heart);…Paris changes! but naught in my melancholy

Has stirred! New palaces, scaffolding, blocks of stone,

Old quarters, all become for me an allegory,

And my dear memories are heavier than rocks.

The urban landscape thus becomes a kind of symbolic network, in which each image—“palaces, scaffolding, blocks of stone”—takes on allegorical meaning for the urban wanderer: telling a story of a history already concluded. Urban space, with its network of personal associations, becomes a graveyard of memory.

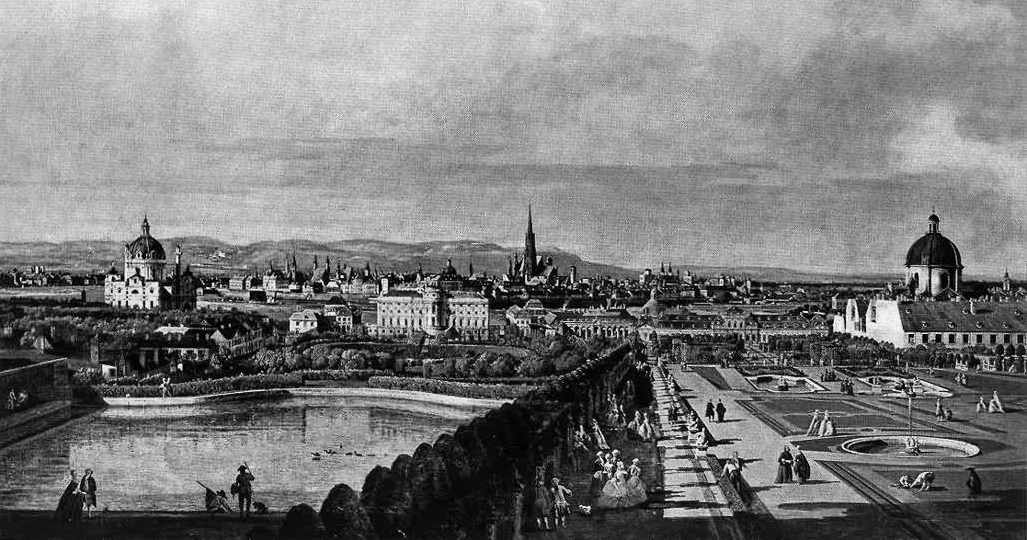

The interplay of absence and presence takes on an even more poignant character in Stefan Zweig’s depiction of Vienna. An upper-middle-class Austro-Hungarian Jew who lived through the horrors of much of two World Wars before his suicide in 1942, Zweig crafts less story than elegy: accounts of exiles in empty cafes, faded resort towns, off-season hotels. Yet it is Vienna—once, to quote Zweig’s wistful autobiography The World of Yesterday, the capital of “the old Habsburg Empire that had once ruled Europe, unsullied in its old glory,” now a shadow of its pre-war self—whose story eclipses that of Zweig’s characters.

The disparity between present and past—heightened by the presence of buildings built in eras gone —grounds Zweig’s experience of urban melancholy. Writing of Vienna’s poverty in the post-war years, Zweig condemns the influx of foreign tourism keen to capitalize on the “cadaverous” Austrian krona. “Every hotel in Vienna was filled with these vultures; they brought everything from toothbrushes to landed estates, they mopped up private collections and antique shop stocks before their owners, in their distress, woke to how they had been plundered. Humble hotel clerks from Switzerland, stenographers from Holland, would put up in the deluxe suites of the Ringstrasse hotels.” The concrete reality of the hotels—extant physically but not psychologically—only enhances, for Zweig, the awareness of the absence of those old Viennese within them.

Thus defines one of Zweig most moving stories, his 1929 “Mendel the Bibliophile,” the story of a narrator in search of his old acquaintance, a book-collector who suffered imprisonment at the hands of wartime authorities. Here, the archetypical Viennese cafe, stuffy, smoke-filled, yet decorated with the trappings of new Vienna—“obviously new” velour sofas, a “shiny aluminum till”—prompts the narrator’s existential anxiety:

I was aware that I must have been here once before, years ago, and that a memory of some kind was connected with these walls, these chairs, these tables, this smoky room, apparently strange to me. But the more I tried to pin down that memory, the more refractory and slippery it was as it eluded me… Nonetheless, I knew I had been here once before…and something of my own old self, long since overgrown, lingered here invisibly, like a nail hidden in wood. I reached out into the room, straining all my senses, and at the same time I searched myself.

Only then are we given the café’s name—Café Gluck on the Alserstrasse; only then does the narrator remember his days here with the titular Mendel. The café becomes a repository of the narrator’s repressed memories of the world before wartime; his existential melancholy a response to seeing the physical remnants of what is culturally absent.

Yet few cities in literature have become as synonymous with melancholy as Trieste, the port at the border of Italy and Slovenia that housed literary exiles James Joyce and Richard Francis Burton, among others. Joyce memorialized the city as triste Trieste—riffing on the similarities between the city’s name and the French word for sadness. The travel writer Jan Morris in her 2001 travel book Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere, writes most explicitly on Trieste’s tristesse.

Melancholy is Trieste’s chief rapture. In almost everything I read about this city, by writers down the centuries, melancholy is evoked… it is… like our Welsh hiaeth, expressing itself in bitter-sweetness and a yearning for we know not what.

This yearning, Morris goes on to explain, arises from the disconnect between Trieste’s present and remnants of its onetime glory. Like Vienna, the once-Habsburgian Trieste has changed radically in the twentieth century: its Austro-Hungarian-style buildings, its baroque squares all hint at a grandeur that contemporary Trieste cannot match. As Morris puts it, “They are only shadows now, though, these vestiges of Habsburg Trieste, like so much in this crepuscular city. The great steam locomotives do not hiss in the station now, the Sudbahn station-master no longer welcomes important personages in his tight-buttoned livery; there is no express to Vienna anymore….”

Trieste’s modern urban landscape points to a world we cannot reach, to what has been lost and what remains. Duke Maximilian’s still-standing Miramare Castle, or the princely palace at Duino, only serve to reminds us of the inevitability of history’s forward march. Writes Morris: “Trieste makes one ask sad questions of oneself. What am I here for? Where I am going? It had this effect upon me when I was in my teens…I feel it still.”

She goes on to quote Wordsworth —“Men are we and must grieve when even the Shade/of that which once was great is passed away.” That shade is encoded in the melancholy city itself: which points to, but never can be, the city we imagine it might once have been.

Nature repeats itself. That which dies is reborn; night becomes day; dirt nurtures seed. But cities are irreducible, irreproducible. When the men who have built them die out, when the marches of history that leave their architectural footprints on facades and street-corners, fountains and piazzas, have moved onwards, what survives of cities is only memory: indications of a particular person’s handiwork at a particular, irrepeatable point in time. The face of a stone angel above a doorway, the curve of a column, figures carved in wrought-iron gates all meant something to someone, once, but now are only testaments to ages gone by. Historic cities are, after all, the legacy of dead men.

To walk in the country is to walk in and among life. That which is growing is growing of its own accord; there is a dynamic force—what the Romantic poets called Nature naturans—that suffuses the natural existence. A single blade of grass may be impermanent; a field of grass is not. But to walk in a city is to walk among ghosts, the narratives of onetime denizens building up like layers of clay shards.

In Baudelaire’s Paris, Zweig’s Vienna, Morris’s Trieste, the feeling of melancholy comes from a keen awareness of the city as simultaneous repository and tomb: a place where something of the past remains, but where such remnants only call attention to what is absent. They denote the cleavage between past and present, between the city-that-was and the city-that-is: reminders of the people that no longer dwell there. The houses are there, inhabitants are not. The Hofburg is there; the Habsburgs are not. The melancholy city is a body without soul.

The phrase “mai piu retornerai”—return no more!—that dominates the final pages of Triestine novelist Italo Svevo’s Senilità, and recurs in Morris’s own text, is the motto of the melancholy city. In The Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton describes melancholy as the “character of Mortality” And it is this awareness of mortality that prompts, for our authors, the experience of urban melancholy. In mourning what cannot return, they mourn what nature—ever-recurring—cannot embody: the finality of death.