God hath given you one face, and you make yourselves another —Hamlet

The Bermuda Triangle of Asian men, masculinity, and media exposure is exhaustively documented elsewhere, so I’ll keep this recap brief. On the rare occasions when Asian men appear in American media, they typically play castrated nerds, inscrutable villains, servants, sidekicks, or self-humiliating clowns. They may be talented or virtuous, but not thinking / feeling symbolic creatures capable of complex expression. The roll call of ignominy includes Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles, Hop Sing in Bonanza, William Hung, Psy ((Yeah, I know this is contentious. While Psy’s not clownish just because he’s Asian, it’s hard to contest that once “Gangnam Style” crossed the Pacific, his chubbiness, inscrutability, and slapstick posturing transformed the song from a regional satire of materialism (which few non-Koreans would pick up on) into a burlesque of Asian men, incongruously aping the celebrity lifestyle that Asian men in America are as a rule denied. Not his fault, but still: unfortunate.)) of “Gangnam Style,” and Ken Jeong in The Hangover; then there’s the history of cinematic yellowface, from the Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu mega-franchises to various roles by Mickey Rooney, Katherine Hepburn, John Wayne, Marlon Brando, Ingrid Bergman, Jerry Lewis, Fred Astaire, Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney (Sr. and Jr.), Alec Guinness, Yul Brynner, Eddie Murphy (!), all the way up through the recent Cloud Atlas fiasco and Mickey Rourke in the upcoming Genghis Khan.

Beyond the generic problems of cultural appropriation and Orientalism, yellowface plays off of the idea that Asians are interchangeable, and that any face, no matter how inauthentic, will suffice to represent them. It is intrinsically dehumanizing, because the face is coupled to identity—various forms of physiognomy ((The so-called Mongoloid phenotype that identifies Asianness is remarkable in that its distinguishing features are concentrated in the head, especially the face. Yellowface is, of course, a misnomer—Asian people are no more yellow than white people are white (to paraphrase one of Marilynne Robinson’s offhand remarks at a lecture, white people are mostly pink).)) and craniometry were accepted as scientific fact up until the early 20th century, and the word character itself derives from kharaktēr, a tool used to engrave distinguishing marks on the faces of coins. To be Asian and male and to watch Asian males in film or television is uncanny; you’re aware they don’t resemble you, yet are presumed to represent you. You feel as if you’re losing possession of your face.

Most attempts to counter this phenomenon fail in the same subtle way: the films of Chris Chan Lee and Justin Lin, Harold and Kumar, Steven Yeun on The Walking Dead and Daniel Dae Kim on Lost all read like counterpropaganda, with a condescending gliberalism that upholds certain stereotypes and crudely inverts others, in either case affirming them—Hey, we know Asians are the last guys you’d expect to be sexy or powerful but check THIS out! And yes, they ARE smart! The brief tremor of attention around the New York Knicks’s Jeremy Lin was notable mainly for the dustclouds of racism it kicked up (“Some lucky lady in NYC is gonna feel a couple of inches of pain tonight,” tweeted one sports columnist). We can feel good about Sessue Hayakawa, but his sort of stardom hasn’t recurred post-WWII. At any rate, it’s telling how often any remotely human Asian man on film is hailed as “refreshing.”

———

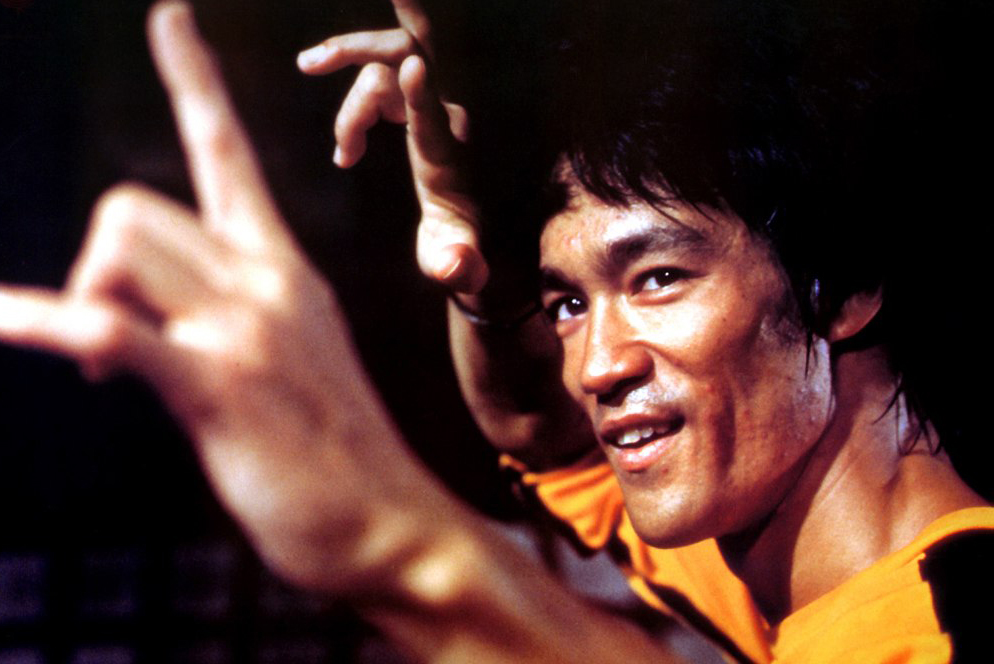

Similar to the way Hitler pops up in arguments as a lazy benchmark for absolute evil, Bruce Lee invariably gets trotted out as the show pony that debunks Asian male underexposure in principle. Never mind that he birthed a stereotype all his own, the Asian as stoic martial artist—finally, an Asian man was being admired worldwide for his physique, embodying an intimidating-yet-likeable attractiveness. He was moreover highly self-possessed, touting individuality and adaptability as paramount virtues. Lee’s cultural apex coincided with Nixon’s opening of relations with China; conscious of his ambassadorial status, he asserted his desire to portray the “true Oriental” in his films. “It’s always the pigtails, and bouncing around, chop-chop, you know, with the eyes slanted and all that, and I think that’s very, very out of date,” he lamented in an interview, later adding, “They’re trying to get me to do too many things that are really for the sake of being exotic.”

Fame brought Lee greater creative control. In 1972 he began filming The Game of Death, intended to showcase his Jeet Kune Do martial arts philosophy, but he put the project on hiatus to film Enter the Dragon. Shortly after completing Enter the Dragon and returning to The Game of Death, Lee died of cerebral edema triggered by an allergic reaction to a painkiller; the project was reconceived and released in 1978 by co-producer Raymond Chow and Enter the Dragon director Robert Clouse, who culled about eleven minutes from Lee’s footage to fashion an entirely different 140-minute movie. Clouse blurbed: “This electrically charged film contains the most spectacular footage of the Chinese-American superstar ever filmed. It is, we feel, a fitting memorial to Bruce Lee,” stopping short of naming exactly who the “Chinese-American superstar” is ((Another promo video, released two years before the movie’s premiere, bizarrely casts white actors in the role of the production company’s Asian executives.)). Thus the film that Bruce Lee intended to be the clearest articulation of his personal philosophy had almost no Bruce Lee in it.

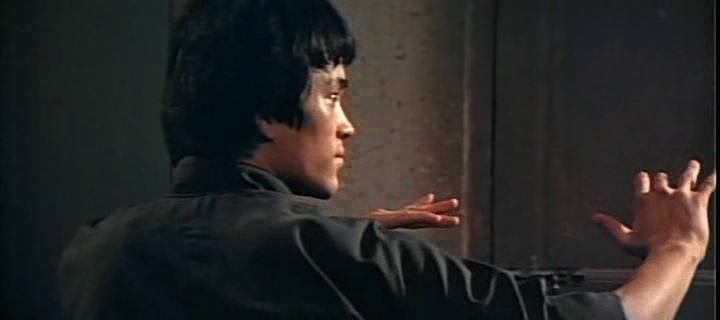

Then how did they manage to make the film at all? The lead role of Billy Lo is played primarily by a body double (Tai Chung Kim) and a stunt double (Yuen Biao), while several of his lines are overdubbed in that flat, contractionless, overpolite diction that bad actors use to evoke East Asian accents. Bruce Lee’s trademark dove-and-gull kiyaps are dubbed into the battle scenes.

And most importantly, you almost never see his face. It’s concealed behind shades, bandages, helmets, blood, fake beards, and masks; with long distance shots, obscuring angles, premature cutaways, and even a cardboard cutout. And Billy Lo is played by multiple doubles—to believe in Billy requires us to see different Asian men with distinct faces and bodies as a single person. So the Asian male megastar succumbs, after all, to interchangeability.

Is this proof of deliberate, pernicious racism? No, it’s just a commercially pragmatic workaround—people watch Bruce Lee movies because Bruce Lee’s in them. Even if it’s wildly inconsistent and narratively incoherent, even if old footage is recycled, the audience must have Bruce Lee. Yes, I’m aware that The Game of Death is mainly a schlocky attempt to cash in on leftover footage, and that using body doubles to replace the dead is neither unusual nor exclusive to Asian men (though this is probably the only such movie that’s also about the death of a lead actor). But in its efforts to absorb Lee’s death into its plot, the film becomes something more: a bizarre sequence of layered simulacra, of double entendres and trifocal ironies, overspilling the boundaries of its own fictional ontology into reality. A clash between reality and fiction, elevating racial insensitivity to ontological quandary.

I may be criticized for obtuse misreading. But misreading is a fine way to approach miswriting, and to being misread. The Game of Death is not quite itself—it is a duplicate, the successor of a stillborn, a statement of self-possession that, after its death, became possessed by a false version of itself, a doppelganger called The Game of Death.

Face Value

Always be yourself, express yourself, have faith in yourself, do not go out and look for a successful personality and duplicate it. —Bruce Lee

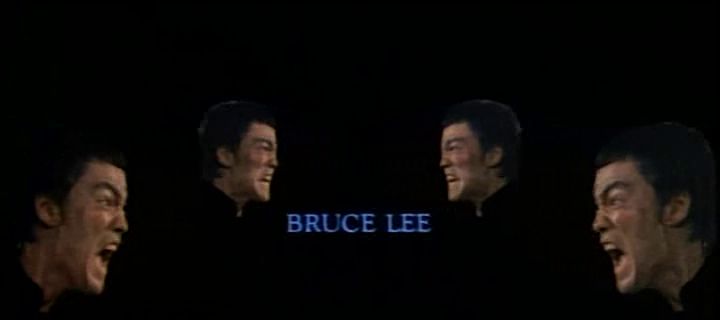

The first thing to appear is two rows of screaming, disembodied Bruce Lee heads cascading down either side of the screen, pair after pair of faces facing each other:

After an intro sequence, the movie opens on another movie: the famous Coliseum duel from 1972’s Way of the Dragon. With his face bloodied, Lee assaults the camera; the footage cuts away briefly to a film crew, revealing that they’re shooting this scene for a movie, while a disclaimer caption appears:

After an intro sequence, the movie opens on another movie: the famous Coliseum duel from 1972’s Way of the Dragon. With his face bloodied, Lee assaults the camera; the footage cuts away briefly to a film crew, revealing that they’re shooting this scene for a movie, while a disclaimer caption appears:

THE CHARACTERS AND INCIDENTS PORTRAYED AND

THE NAMES USED HEREIN ARE FICTITIOUS, AND ANY

SIMILARITY TO THE NAME, CHARACTER, OR HISTORY

OF ANY PERSONS IS ENTIRELY COINCIDENTAL AND

UNINTENTIONAL.

Taken at face value, this immediately triggers several weird dissonances. The movie abundantly uses footage from real movies and events, and its Bruce Lee similarities are anything but unintentional (unless you mean Bruce Lee’s intentions). And the movie is stuffed with coincidences, the most glaring of which is that the iconic martial arts movie star Bruce Lee plays the iconic martial arts movie star Billy Lo; a scene from the Bruce Lee movie Way of the Dragon is a scene in a fictional Billy Lo movie within the Bruce Lee movie The Game of Death. This by itself would be merely coincidental; but we’ll soon see that the movie is, as it claims, “entirely coincidental.”

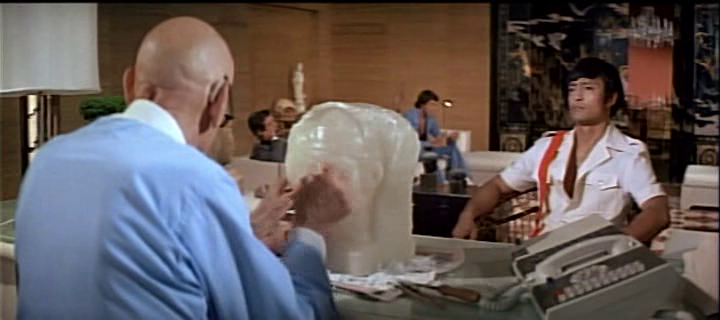

After Lee KO’s an earnest, hirsute Chuck Norris, the director yells cut, and something strange happens: the film quality abruptly improves, and Billy’s physique deflates, becoming less muscular, less glisteningly marmoreal; he’s gained a mole on his chin, a slimmer nose, an overbite, higher pants, and a longer, shaggier haircut.  He is one of Bruce Lee’s body doubles, shuffling hurriedly offscreen with a stooped head. Within seconds of his appearance, a stage light crashes to the floor, narrowly missing him. An archival shot of Bruce Lee’s face briefly blips on, and then everyone pretty much shrugs, and Billy retires to his dressing room, where a villain awaits: Steiner, a smirking bigwig of a media conglomerate that controls its clientele through brute intimidation. The Syndicate wants Lo to sign a contract, which would give them control over his appearance in movies (in industry terms, they want him to play the game). Citing a stubborn guitarist whose fingers they severed, Steiner threatens: “A man has got to have all of his parts to make it. Don’t you agree with that, Billy?”

He is one of Bruce Lee’s body doubles, shuffling hurriedly offscreen with a stooped head. Within seconds of his appearance, a stage light crashes to the floor, narrowly missing him. An archival shot of Bruce Lee’s face briefly blips on, and then everyone pretty much shrugs, and Billy retires to his dressing room, where a villain awaits: Steiner, a smirking bigwig of a media conglomerate that controls its clientele through brute intimidation. The Syndicate wants Lo to sign a contract, which would give them control over his appearance in movies (in industry terms, they want him to play the game). Citing a stubborn guitarist whose fingers they severed, Steiner threatens: “A man has got to have all of his parts to make it. Don’t you agree with that, Billy?”

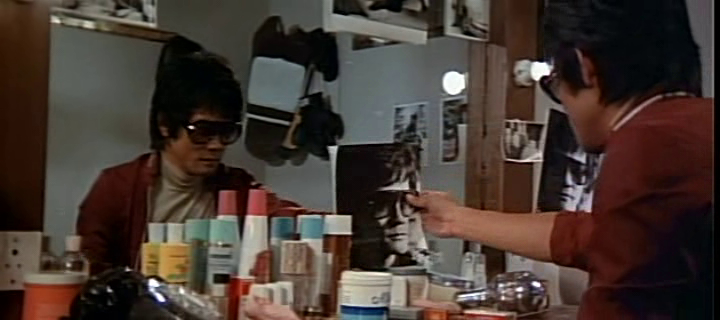

Then follows an infamous shot, the first of many significant mirror scenes. Billy Lo sits at his dressing room mirror, to which a ludicrous cutout of Lee’s face is affixed, imperfectly concealing Billy’s face. Unlike the rest of the film, in which Billy Lo’s face is concealed by camera angles and disguises, this shot conceals Billy’s face with another face—the face of the man he’s supposed to be. We’re meant to accept that this grainy static mask really is his face, even though it’s impossible not to notice Billy’s body drifting around behind it ((Do I even need to point out that mirrors are metaphors for doubleness and self-awareness, or that the climactic fight from Enter the Dragon has Bruce Lee shattering an entire roomful of mirrors?)). Billy’s face is the face of a dead man.

Then follows an infamous shot, the first of many significant mirror scenes. Billy Lo sits at his dressing room mirror, to which a ludicrous cutout of Lee’s face is affixed, imperfectly concealing Billy’s face. Unlike the rest of the film, in which Billy Lo’s face is concealed by camera angles and disguises, this shot conceals Billy’s face with another face—the face of the man he’s supposed to be. We’re meant to accept that this grainy static mask really is his face, even though it’s impossible not to notice Billy’s body drifting around behind it ((Do I even need to point out that mirrors are metaphors for doubleness and self-awareness, or that the climactic fight from Enter the Dragon has Bruce Lee shattering an entire roomful of mirrors?)). Billy’s face is the face of a dead man.

Steiner’s quip about men and their indispensible parts isn’t just a threat, it’s a fact—an actor’s body is his asset, especially his face, and you could hardly make a movie without it. Steiner delivers this line just before we see that Billy Lo doesn’t have his own face. Why would a character in this movie, during the single most egregiously fake shot in the whole movie, emphasize that Lo isn’t Lee? Maybe he’s taunting Billy, because he knows Billy isn’t Bruce Lee. Remember, Steiner is basically a surrogate for the producers of The Game of Death: he’s a white film producer who controls how Billy is portrayed in his movies. What we’re watching is Steiner’s point of view: he doesn’t see Billy Lo, he sees Bruce Lee.

A flash of footage from Way of the Dragon plays—as if to assert poltergeistic vengeance for the oblivious Billy, Bruce Lee reappears for half a second, winds up for a strike, and Tai Chung Kim completes the backfist that sends Steiner tumbling across the room.

From this point forward, The Game of Death becomes an absurd parade of disguises. Billy dons a huge pair of celeb-incognito sunglasses that stay on for the next half hour, even as the next scene has him battling in a dark street against a gang of helmeted Syndicate thugs who ambush him, even when they kick him upside the face. After that he’s sitting at a dim candlelit dinner, and he’s still wearing them. He and Ann are joined by his mentor Jim Marshall ((Jim is played by Gig Young, a severe alcoholic; shortly after The Game of Death’s release, he killed his young wife and then himself for unknown reasons.)), who warns Lo about the conspiracy against him, and that he’s just “one of a couple of thousand public personalities that they own all of, or a piece of.” With characteristic ambiguity, he could be referring either to Billy Lo’s relationship to the Syndicate, or to Bruce Lee’s role in The Game of Death.

Billy, fiddling with a small jade figurine, delivers a lame quasi-Confucianism: “It is better to die a broken piece of jade than to live a life of clay.” He snaps the figurine.

Cut to Bad Guy HQ: Dr. Land, Steiner’s accomplice and big cheese, sits at his desk carving a wax face—primed by the previous shot, it’s easy to mistake its pale glossy opacity for jade. His model is Dan Inosanto, one of the few credited Asian characters.

Billy remains uncooperative after subsequent threats and beatdowns, so the Syndicate decides to snuff him out, casting one of their hitmen as an extra in the final scene of Billy’s movie, in which eight men shoot at Billy. The assassin loads his gun with a real bullet. The director calls action, and the scene cuts away to archival footage of Bruce Lee bum-rushing the camera. When they fire, Billy Lo falls with his face bloodied.

Billy remains uncooperative after subsequent threats and beatdowns, so the Syndicate decides to snuff him out, casting one of their hitmen as an extra in the final scene of Billy’s movie, in which eight men shoot at Billy. The assassin loads his gun with a real bullet. The director calls action, and the scene cuts away to archival footage of Bruce Lee bum-rushing the camera. When they fire, Billy Lo falls with his face bloodied.

As the cameras shoot Billy being shot, the assassin shoots Billy. The assassin acts as if he’s shooting Billy, and everyone believes he isn’t, but he is. Billy is presumed dead, but he isn’t, but the man who’s supposed to be playing him is. And Billy is falsely killed in The Game of Death as he’s being killed in the film within The Game of Death.

As the cameras shoot Billy being shot, the assassin shoots Billy. The assassin acts as if he’s shooting Billy, and everyone believes he isn’t, but he is. Billy is presumed dead, but he isn’t, but the man who’s supposed to be playing him is. And Billy is falsely killed in The Game of Death as he’s being killed in the film within The Game of Death.

To elude the Syndicate, Billy fakes his death; throughout the movie he racks up at least six high-profile murders, so it’ll be a while before he returns to acting—thus, Billy’s death interrupts his film, just as Lee’s interrupted The Game of Death. But there’s no way his film’s producers would scrap a movie with only one scene left to complete; they would probably finish the movie with a body double and archival footage, the same way that footage of Bruce Lee is used to complete the scene that we see. Or perhaps they’d make an entirely different movie built around scraps of usable footage, like The Game of Death: thus they would end up making a movie like The Game of Death. Or maybe they’d be callous enough to just use the actual footage of Billy Lo’s death, since, after all, the scene is about Billy Lo getting shot. What could be more believable?

If that sounds tasteless and unlikely, it’s not long before you see how plausible it is. In the next scene, Jim Marshall and a doctor stand before a set of x-rays. “The bullet fragmented as it passed through at an upward angle, literally smashing the bone structure of the face,” the doctor explains. Jim asks about the likelihood of Billy having a “normal” appearance. “There’ll be extensive structural changes, a great deal of scar tissue,” the doctor replies. “He’ll be permanently altered, of course, but presentable in any case.”

They enter Billy’s hospital room, where he lies in bed, entirely bandaged except for his eyes. They plan to fake his death to hide him from the Syndicate. “There will have to be a complete falsification of documents,” the doctor says. “Death certificate. Someone will have to inform the press… then there’s the question of a change of identity.

“Identification’s already been taken care of,” Jim says. (Because he’s already changed his identity.)

The doctor adds, “A public funeral? Open casket? After all, he is a celebrity.”

“Don’t worry, John. It’ll be a very believable funeral,” Jim says.

Indeed it’s very believable. In one of the few scenes unmarred by camp, police lines hold back a teeming mass of reporters and rubberneckers in the street, and harried pallbearers strain to bring the casket in. A solemn procession files by the open casket, in which Billy Lo’s fake body can be seen in repose under protective glass. It ought to be believable, since it is, in fact, the actual footage of Bruce Lee’s funeral. Hence the real Bruce Lee’s corpse is used to play the part of Billy Lo’s fake corpse. At his most purely concrete, Bruce Lee plays a fake of a fake of himself.

Crosscut through the funeral footage is a montage of Billy’s face being surgically reconstructed—just as the movie itself is a reconstruction, salvaged from the fragments that remained of Bruce Lee’s face, bearing only a passing resemblance to the original. (Race is a construct; the face is not, but it can be reconstructed.)

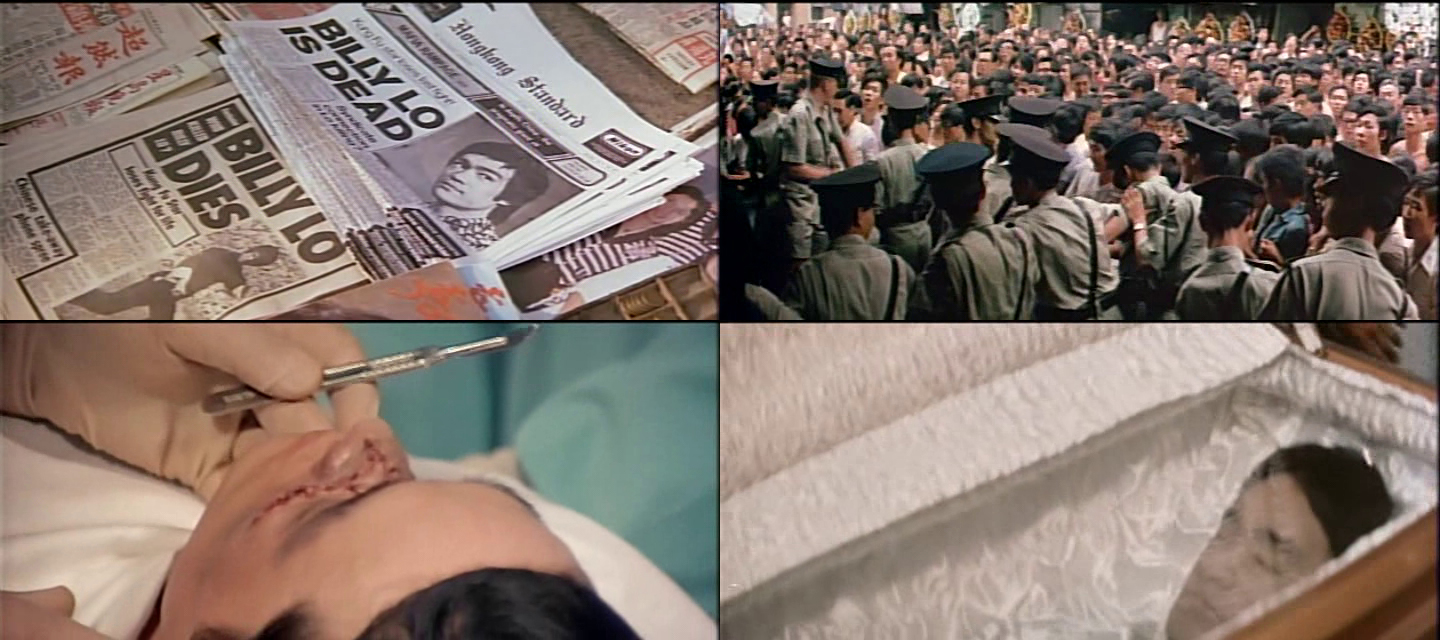

We also see a newspaper whose headline and kicker read: BILLY LO IS DEAD: KUNG FU STAR LOSES LAST FIGHT! With its vague elision of names reminiscent of Robert Clouse’s “Chinese-American superstar,” it’s not even clear who lost the fight; the article runs with Bruce Lee’s photo. The “last fight”—even the papers know it—is the struggle between Bruce Lee and Billy Lo.

The scene that follows is a bizarre counterpart to the cardboard-cutout shot in Billy Lo’s dressing room. Recovering from his headshot, Billy Lo scribbles a pair of shades and a beard onto a headshot of Bruce Lee. The bemused doctor asks Billy what he’s doing.

“I’m giving myself a new face: before,” Lo says—he holds Bruce Lee’s defaced face up to the mirror, concealing his own face, which is already concealed by bandages, and isn’t the same as the face in the photo, which is concealed—“and after. Much better.”

“I’ve already told you, Billy,” the doctor says, “you’re going to have a normal appearance again.” But what does the doctor mean by “normal” here? The best he could do is to restore Billy’s old face, recover it, but it still wouldn’t look like Bruce Lee. Billy knows this, and has covered up his fake face under three layers.

“I’ve already told you, Billy,” the doctor says, “you’re going to have a normal appearance again.” But what does the doctor mean by “normal” here? The best he could do is to restore Billy’s old face, recover it, but it still wouldn’t look like Bruce Lee. Billy knows this, and has covered up his fake face under three layers.

The doctor leaves. “The new Billy Lo,” says the old Billy Lo, to himselves.

A Life of Clay

It just so happens that people are different. —Bruce Lee

After delivering a stillborn son, Bruce Lee’s parents superstitiously assigned their next son a female name, to throw off spirits who would possess him; the name, Sai Fon, means little phoenix. They changed this to Jun Fan, a homophone of return again; they altered the spelling in accordance with Chinese homonymic naming taboo, which forbids naming a child precisely after his predecessors. Bruce Lee was his English name.

From birth, Bruce Lee was a triple revenant: the successor of a stillborn, a phoenix, one who returns again. From birth, Bruce Lee had three names. From birth, Bruce Lee was a doppelganger thrice-over—pseudonymic male, homonymic descendant, homophonic echo. A human pun.

———

Fully recuperated, Billy leaves the hospital unbandaged. His recovered, uncovered face is identical to his old face, except for the baseball-like seams on either cheek. True to his doodle, he re-covers his face with a fake beard (which for some absurd reason is brown) and dons his trusty shades. Why would he disguise himself? Maybe as a celebrity, he feels he’s recognizable in spite of the scars; the lowly Lo / Lee must lay low. But if the whole point is that he’s disfigured—if there were “extensive structural changes” and he was “permanently altered”—he wouldn’t need a disguise. In fact, from a practical storytelling standpoint, this would’ve been an opportunity to get away with openly using an actor who didn’t look like Bruce Lee. But The Game of Death eschews that option; the deluded fiction of Bruce Lee’s resurrection continues, his face unchanged but concealed.

After infiltrating Dr. Land’s home and failing to murder him, Billy follows the Syndicate to their martial arts championship in Macau, where he dons a fake Fu Manchu wig and facemask that looks vaguely Klingon. Earlier we saw this costume lying around on his dressing room makeup table; one would suppose that Billy had previously worn this costume for his movie, which means that he’s disguising himself in The Game of Death the same way he did in his unfinished movie. (Which means he disguises himself in that movie too!)

After infiltrating Dr. Land’s home and failing to murder him, Billy follows the Syndicate to their martial arts championship in Macau, where he dons a fake Fu Manchu wig and facemask that looks vaguely Klingon. Earlier we saw this costume lying around on his dressing room makeup table; one would suppose that Billy had previously worn this costume for his movie, which means that he’s disguising himself in The Game of Death the same way he did in his unfinished movie. (Which means he disguises himself in that movie too!)

His first task is to prevent Ann from revenge-killing the Syndicate bosses as they spectate. With spirit gum gleaming at his hairline, he intercepts her as she pulls a gun from her purse, telling her to stop. (Implausibly, she doesn’t turn to face the man who’s seizing her hand and whispering in her ear with her dead boyfriend’s voice until after he’s left.) Next Billy goes after Carl Miller, a cocky Syndicate thug who’s just won the championship match; Billy follows Carl to his locker room and challenges him; we see him remove his face mask. During this fight we get direct glimpses of the body double’s face, though mostly sidelong or at a distance, and the first thing we notice is that all the injuries to Billy Lo’s exposed face—the “great deal of scar tissue”—have vanished!

How to explain this miracle? Near the beginning of the movie, Steiner mentions that “the fight is only weeks off,” so not much time has passed since the attack. It’s not a glancing continuity error, because it lasts through the whole scene; in fact, The Game of Death de-deforms Billy Lo precisely to preserve continuity, because this scene uses footage of Bruce Lee’s unscarred face from Way of the Dragon. They could’ve sidestepped the problem by leaving out the Bruce Lee footage, but rather than remain consistent with the major plot point of Billy’s deformity, The Game of Death opts to resurrect Bruce Lee. But soon enough, the scars return. After killing Carl Miller, Billy sits before his makeup mirror. His scars have returned. He gazes forlornly at a headshot of himself—of Tai Chung Kim wearing sunglasses, not Bruce Lee, as in his previous headshot-at-the-mirror scene—then removes his shades and applies some kind of clear gel to his face ((Does this gel explain the selective disappearance of Billy’s scars—is it a miracle salve? Probably not. Billy disguises himself in the previous two scenes; in the first, he doesn’t bother concealing his scars, so we know he’s willing to expose them. In the second, he has no scars under his old guy mask: why would he conceal his scars with makeup when he’s already masked?)). This is the closest still shot of Tai Chung Kim’s face we get, and the first time Billy sees his own uncovered face ((Right before the cardboard-cutout shot, Billy sits with his face uncovered in front of his mirror, but he doesn’t look at it.)). Why does he look so uneasy? Is he suffering a pang of vanity? Worried about his film career? About what his girlfriend Ann will think?

How to explain this miracle? Near the beginning of the movie, Steiner mentions that “the fight is only weeks off,” so not much time has passed since the attack. It’s not a glancing continuity error, because it lasts through the whole scene; in fact, The Game of Death de-deforms Billy Lo precisely to preserve continuity, because this scene uses footage of Bruce Lee’s unscarred face from Way of the Dragon. They could’ve sidestepped the problem by leaving out the Bruce Lee footage, but rather than remain consistent with the major plot point of Billy’s deformity, The Game of Death opts to resurrect Bruce Lee. But soon enough, the scars return. After killing Carl Miller, Billy sits before his makeup mirror. His scars have returned. He gazes forlornly at a headshot of himself—of Tai Chung Kim wearing sunglasses, not Bruce Lee, as in his previous headshot-at-the-mirror scene—then removes his shades and applies some kind of clear gel to his face ((Does this gel explain the selective disappearance of Billy’s scars—is it a miracle salve? Probably not. Billy disguises himself in the previous two scenes; in the first, he doesn’t bother concealing his scars, so we know he’s willing to expose them. In the second, he has no scars under his old guy mask: why would he conceal his scars with makeup when he’s already masked?)). This is the closest still shot of Tai Chung Kim’s face we get, and the first time Billy sees his own uncovered face ((Right before the cardboard-cutout shot, Billy sits with his face uncovered in front of his mirror, but he doesn’t look at it.)). Why does he look so uneasy? Is he suffering a pang of vanity? Worried about his film career? About what his girlfriend Ann will think?

Billy’s unease makes lots of sense if you pause to consider Freud’s concept of the Uncanny. An uncanny experience is one that awakens repressed fears: “that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.” Uncanny things are both “familiar and agreeable” and “concealed and kept out of sight,” things that “ought to have remained secret and hidden but [have] come to light.” Classically uncanny scenarios include: “intellectual uncertainty whether an object is alive or not,” “involuntary repetition,” encounters with people whose “intentions to harm us are going to be carried out with the help of special powers,” and anything “in relation to death and dead bodies, to the return of the dead.” If this is starting to sound uncannily similar to Billy Lo’s plight, how about this:

Billy’s unease makes lots of sense if you pause to consider Freud’s concept of the Uncanny. An uncanny experience is one that awakens repressed fears: “that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.” Uncanny things are both “familiar and agreeable” and “concealed and kept out of sight,” things that “ought to have remained secret and hidden but [have] come to light.” Classically uncanny scenarios include: “intellectual uncertainty whether an object is alive or not,” “involuntary repetition,” encounters with people whose “intentions to harm us are going to be carried out with the help of special powers,” and anything “in relation to death and dead bodies, to the return of the dead.” If this is starting to sound uncannily similar to Billy Lo’s plight, how about this:

These themes are all concerned with the phenomenon of the ‘double,’ which

appears in every shape and in every degree of development. Thus we have

characters who are to be considered identical because they look alike. This

relation is accentuated by mental processes leaping from one of these

characters to another—by what we should call telepathy—, so that the one

possesses knowledge, feelings and experience in common with the other. Or

it is marked by the fact that the subject identifies himself with someone else,

so that he is in doubt as to which his self is, or substitutes the extraneous self

for his own. In other words, there is a doubling, dividing and interchanging

of the self. And finally there is the constant recurrence of the same thing—the

repetition of the same features or character-traits or vicissitudes, of the same

crimes, or even the same names through several consecutive generations.

Freud goes on to remark that because more things are possible in fictional worlds, uncanny effects are encountered more often in literature than in reality, and events that are uncanny in fiction would be less so in reality. But he’s quiet on the relation between fiction and reality. Ancient Greek drama often used multiple masked actors to play the same role ((Barthes wrote that the function of these masks was to create the illusion that the actors’ speech was emanating from the Underworld.)); the mask, not the actor, defined the role (the chorus members, who all wore the same mask, were meant to be considered as a single character). Actors using their own real bodies makes cinema inherently uncanny, its characters Janus-faced, two-personed: particularly when the actor is dead, and double-particularly when one knows the actor died before the movie’s release. When different movies feature the same actor, it’s hard not to see the characters as reincarnations of each another—no matter how different Vito Corleone, Stanley Kowalski, and (The Teahouse of the August Moon’s yellowface) Sakini are, Brando is always clearly identifiable. Hollywood’s derivativeness—all its adaptations, spinoffs, sequels, reboots, and genre conventions—only reinforces this feeling of secret correspondence between films ((Freud accounts for how Billy, Steiner, Ann, Jim, and Dr. Land all seem to intuit Billy’s condition without ever being quite conscious of it, speaking of it only in double entendre: by “what we should call telepathy.”)).

When Billy Lo sees his unmasked face for the first time, he must be seized by that same uncanny disquiet, the fear he’s been repressing—that his face is not the face people see when they look at him. His real face is damaged.

———

Billy isn’t the only one who’s disturbed. One odd consequence of Billy Lo’s self-concealment is that Ann Morris, ((Played by Colleen Camp, who coincidentally starred in the B movie Death Game the previous year.)) Billy’s loving girlfriend, never sees Billy’s face until the end of the movie. He wears sunglasses whenever he’s with her ((Fussy people might argue that Ann sees him when he’s shot. He approaches her in sunglasses and tells her to leave for her own safety, then turns away from her until the cameras roll; the scene switches to archival footage. At best she’d be able to see him at a distance while sprinting and jumping.)), and at his funeral she never looks into his casket. In a movie that’s all about physical contact, the only time Ann and Billy even touch is in a sterile one-armed hug shot from a distance ((I’m reminded of Romeo Must Die (2000)—the total absence of chemistry between Jet Li and Aaliyah in that adaptation of the West’s token romance is necessarily ironic. An alternate ending that had them kissing was panned by test audiences.)).

Ann doesn’t take Billy’s death well. Mascara-stained, she watches the funeral from the sidelines; seeing the Syndicate honchos in attendance, she spits in their faces. Jim takes her away and tries to calm her. “God knows the police would like to nail them, but there’s no way to prove it,” he says, in that annoying way that people use fatalism as consolation. Before walking away and fainting, Ann screams: “Don’t you understand anything? Everybody looked at them, but not one person could see anything!”

At first, this grief-addled gaffe seems clear enough. She seems to echo Jim’s point—that everyone knew the Syndicate ordered the attack, but couldn’t prevent it. But Ann clearly means to contradict him, so who does she mean by “them”? The assassin? She doesn’t know who he is. The Syndicate? Nobody was looking at them.

But if we take Ann at face value, her words demand parsing. First, she makes a pointed distinction between looking and seeing—raw perception vs. understanding, apparent vs. underlying meaning. She also ends both sentences with the word anything: when you look at something, you can’t see anything, you can only see something. One thing, distinct from others. In dark hallways or inkblots you may see something ambiguous, but you still don’t see anything.

What if we repunctuate it: “Everybody looked at them, but not one person! Could see anything!” So she’s saying that Billy Lo is multiple people: them, not one person. Them could refer to Asians, and the way the Asian stereotype subsumes individual identity into a faceless, collective otherness. And them could also refer to Bruce Lee and his doubles. Everyone has been looking at Asian men, at Bruce Lee and Billy Lo and Tai Chung Kim and Yuen Biao, not one person, i.e. an individual.

At a sanatorium, Ann recovers from the trauma of losing Billy. When Jim comes to visit her, the nurse tells him, “She’s ready to see a familiar face.”

———

“I’m now convinced that the man who attacked me was in disguise,” Dr. Land says, perceptively. He begins to suspect Lo faked his death, and asks Steiner whether he looked in the casket; a chagrinned Steiner replies, “He didn’t look exactly the same, but what the hell, they never look exactly the same.”

Another vague plural pronoun, like Ann’s them. He’s talking about how people look different after death, of course, but the other entendres are clear: he’s acknowledging that Billy Lo is played by multiple actors who never look exactly the same. Asian men don’t look the same, but people see them that way. A dead Bruce Lee does not look like a living Billy Lo; nonetheless, Steiner was fooled. He looked in the casket at something different than what he knew he should see, and because it suited him, he saw what he wanted to see. It didn’t matter if the person in the casket was dead or alive, human or inhuman, so long as he had an Asian face.

Soon Dr. Land and Steiner exhume Billy Lo, finding only a fake clay head. But a fake of who? The funeral scene used footage from Bruce Lee’s funeral: that was the real Bruce Lee in his coffin. The clay head is a fake of Billy Lo, though it really looks nothing like him. And so Bruce Lee’s corpse wasn’t playing Billy Lo’s corpse; it played a clay head, standing in for Tai Chung Kim as Billy Lo, who stands in for a living Bruce Lee. Bruce Lee’s corpse plays a fake of a fake of a living version of himself. Remember Billy’s earlier quote?: “It is better to die a broken piece of jade than to live a life of clay.” A life of clay, it suggests, is a fake life, and a fake life is worse than a real death—but now Lo lives a fake death of broken clay, as Steiner, placing the bladed tip of his cane in in the same spot that Billy was shot, shatters the face, jadedly.

Once Ann gets wise to Billy’s fake-death plot, Billy arranges to meet with her. His scars are gone again—for good, it turns out. With his face obscured in shade, he tells her, “I wasn’t going to see you again. I didn’t want you to see me.”

Once Ann gets wise to Billy’s fake-death plot, Billy arranges to meet with her. His scars are gone again—for good, it turns out. With his face obscured in shade, he tells her, “I wasn’t going to see you again. I didn’t want you to see me.”

“Billy, it’s all right, you have to know that,” Ann says.

“No, not to me it isn’t,” Billy says. “Maybe later, but I have to get used to myself first.”

A-ha! With his scars gone, what else could he be referring to but the fact that if she saw his face, she wouldn’t see Bruce Lee? Or worse: that if she saw his face, she would see Bruce Lee? Billy is uneasy about his identity. He’s not used to himself because his role conflicts with his face, which identifies neither him nor Bruce Lee, but only the Asianness they share in common. Billy knows he has to serve as Bruce Lee’s shade. He is a fictional character conscious of his own inauthenticity, unwilling to show the face from which he is dispossessed, the Asian face that he and Ann must believe, want to believe is Bruce Lee’s—just like the typical viewer of The Game of Death wants to. Billy has at last articulated his motives for concealing himself throughout the film: until he can feel settled in his own individual identity, he’s refusing the audience the Asian face they came to see. Because if he has no face, they can’t mistake it for Bruce Lee’s.

The first and only time Ann ever does see Billy’s face is the last time they see each other, when he rescues her from the warehouse where she’s been kidnapped and tied up. Here Ann plays the archetypal damsel-in-distress, and her rescuer is someone who’s denied the masculine role of knight-to-the-rescue. The reunion is correspondingly perfunctory: as he unties her, she sees his uncovered face, and we see that the gag has chafed her cheeks raw. Billy’s parting words to Ann: “Don’t show yourself, no matter what you hear.”

The first and only time Ann ever does see Billy’s face is the last time they see each other, when he rescues her from the warehouse where she’s been kidnapped and tied up. Here Ann plays the archetypal damsel-in-distress, and her rescuer is someone who’s denied the masculine role of knight-to-the-rescue. The reunion is correspondingly perfunctory: as he unties her, she sees his uncovered face, and we see that the gag has chafed her cheeks raw. Billy’s parting words to Ann: “Don’t show yourself, no matter what you hear.”

Writing about the perception of race, James Baldwin remarked, “…it is one of the ironies of black-white relations that, by means of what the white man imagines the black man to be, the black man is enabled to know who the white man is.” He’s suggesting that the beholder is reflectively defined by how she interprets (or misinterprets) others. Once you’re aware of that, as the beholder or beheld, you can’t help but become self-conscious of how you yourself are misseen. The alienation from one’s own face therefore becomes contagious, like a curse. So when Billy and Ann become mutually visible in the same instant, it’s as though the mere sight of him consigned his scars to her.

———

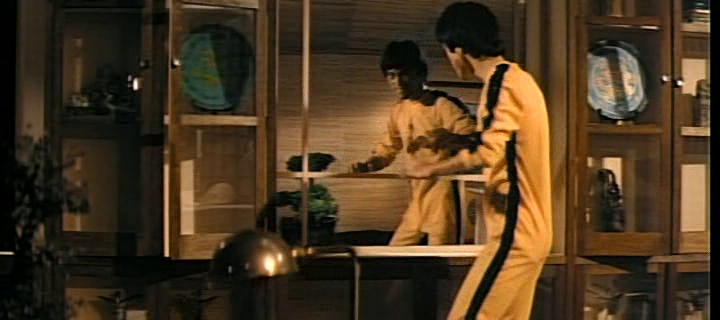

The least coherent, most watchable part of The Game of Death is its conclusion, when Billy perfects his revenge; this is where the 11 minutes of Bruce Lee’s original footage is used. Bruce Lee, all of the sudden visible, fights with characteristic Astairean exuberance, taut negative space, cobra-strikes. He wears his iconic yellow tracksuit, which Lee intended to express a lack of allegiance to any style, his individuality. He has his real face back, his game-face. It’s fun to watch, and nothing if not straightforward; but after spryly murdering two Asian martial artists and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bruce Lee’s eleven minutes are up, and the talent bleeds away. The tracksuit fits like baggy longjohns on the body double, who grapples clumsily with Steiner, as Steiner pointlessly grabs Billy’s face, perhaps to conceal the irony that the man he’s trying to kill is already dead.

Top: Bruce Lee. Bottom: not Bruce Lee.

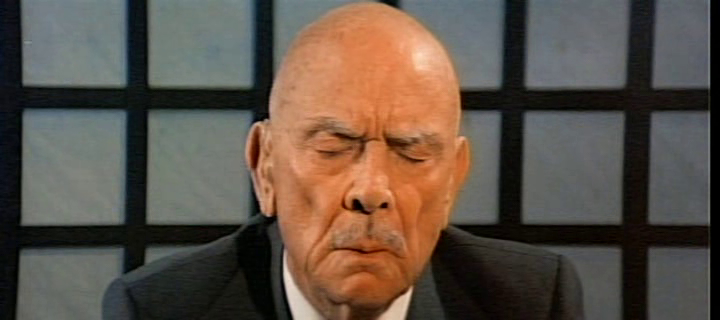

With one more kill to go, Billy finds Dr. Land at his desk with his wrists slashed improperly (not “down the highway,” but “across the road”). In close-up, Land’s face is clearly that of the real actor, Dean Jagger, holding still, rather rosy-cheeked and poised for someone who’s just bled to death.

But he’s not really dead. Dr. Land, who along with Steiner acts as the movie’s stand-in for the power structure that wants to control Billy’s appearance in films, has co-opted Billy’s fake-death strategy, concealing himself with a false face that’s an inverse of Billy’s clay head: the living actor plays the role of the fake dummy. But Billy, the fake who faked his death, is not faked out: “Wax!” he screams, tearing the head off. He hears Dr. Land hiding behind a large mirror, and turns to behold his face at last, unscarred and unobstructed.

But he’s not really dead. Dr. Land, who along with Steiner acts as the movie’s stand-in for the power structure that wants to control Billy’s appearance in films, has co-opted Billy’s fake-death strategy, concealing himself with a false face that’s an inverse of Billy’s clay head: the living actor plays the role of the fake dummy. But Billy, the fake who faked his death, is not faked out: “Wax!” he screams, tearing the head off. He hears Dr. Land hiding behind a large mirror, and turns to behold his face at last, unscarred and unobstructed.

Think back on the progression of the mirror scenes: it begins with Billy masked by Bruce Lee’s face, then with sunglasses, then bandages and a photo of Bruce Lee’s face, sunglasses again, fully revealed but scarred, and now in full view, unscarred. Throughout the film Billy becomes increasingly visible to himself. His facial concealments describe a process of coming into racial self-awareness: first he’s oblivious to the face that Steiner sees as Bruce Lee’s; a trauma forces him to become aware of how he looks to others; for a while he compensatingly, acquiescently models himself after the Asian man people mistake him for; and what does he do when he finally sees his own uncovered face? He takes a leaping kick into his reflection, shattering it.

Think back on the progression of the mirror scenes: it begins with Billy masked by Bruce Lee’s face, then with sunglasses, then bandages and a photo of Bruce Lee’s face, sunglasses again, fully revealed but scarred, and now in full view, unscarred. Throughout the film Billy becomes increasingly visible to himself. His facial concealments describe a process of coming into racial self-awareness: first he’s oblivious to the face that Steiner sees as Bruce Lee’s; a trauma forces him to become aware of how he looks to others; for a while he compensatingly, acquiescently models himself after the Asian man people mistake him for; and what does he do when he finally sees his own uncovered face? He takes a leaping kick into his reflection, shattering it.

That’s the real end of the movie; everything else wraps up in under a minute, as Billy gamely chases Dr. Land off the building’s roof to his death. The credits roll beside a montage of Bruce Lee films. The top credit for Billy Lo goes to Bruce Lee; the final acting credit is for Tai Chung Kim, who receives the lowest billing as Billy Lo.

———

In a much-cited scene from Don DeLillo’s White Noise, two characters visit “The Most Photographed Barn in America.” One of them declares that the barn is so famous that no one can really see it—“Once you’ve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn ((Of course this passage itself is so famous that it might itself be impossible to see.)),” he says, adding, “We see only what the others see.” This formulation is a slight inversion of Ann Morris’s outburst at Billy’s funeral—not one person can see anything because everybody looked at them. But the idea’s the same: to be a notion before you’re a person, to be received pre-cathected in other people’s minds, is to be invisible.

What’s it like to be the barn? How does it feel to be hidden by sight; to have a false face, comprised of the gaze of millions, concealing your own? One response is compliance—to simply assume the anticipated image. Hence the Asian male celebrities willing to propagate stereotypes themselves, on the ironic misguided assumption that any Asian face on the screen, any at all, is good exposure ((There’s yet another irony in the stereotype that Asians love to take and pose for pictures—that cinematic cliché where a throng of indistinguishable Japanese tourists points and snaps photos en masse.)). And the other is to conceal, efface. Those who resent being misseen may find withdrawal attractive; it’s fairly uncanny to see any Asian face, much less a famous one. In an essay about the Virginia Tech shooter, Wesley Yang writes:

You see a face that looks like yours. You know that there’s an existential knowledge you

have in common with that face. Both of you know what it’s like to have a cultural code

superimposed atop your face, and if it’s a code that abashes, nullifies, and unmans you,

then you confront every visible reflection of that code with a feeling of mingled curiosity

and awareness.

When this curiosity and awareness towards similar faces curdles into shame and dissociation, you’re apt to treat your own code-encrusted face with some contempt. Yang sources Cho’s animus in the way people responded to the Asianness of his face—to his college classes he wore “reflector glasses with a baseball cap obscuring his face,” and later adopted a “scarf wrapped around his head, ‘Bedouin style.’ ” And though his outlook was of course psychotic, his inlook is probably familiar to many Asians—just go ahead and look up the mushrooming, vastly disproportionate plastic surgery statistics among Asians in both Asia and America over the past decade. (See?)

Is The Game of Death an allegory for Asian self-regard, or a shoddy exploitative kung fu flick? How should we see Billy? Is he Bruce Lee? Is Bruce Lee alive? Is Bruce Lee real? Can anyone see him? Am I him? Who can tell? Only those who watch us.

✖

Acknowledgements

Most of the examples of yellowface in the early part of the essay are drawn from yellow-face.com and Michelle I.’s “Yellowface: A Story in Pictures” at Racebending.