A friend and I once debated whether critics are helpful or even necessary. She ventured no, citing a New York Times book review that attacked the work of a “seasoned” writer, and basically concluded that the novelist had, in his old age, run out of things to say. In a few hundred words, the article did little more than personally insult work that the author had spent years labouring over. Ideally, though, the point of criticism is to elucidate a piece of work, not recriminate it. In The Paris Review article How Is the Critic Free?, Caleb Crain carefully considers the boundaries of an appropriate critique, and the critic’s freedom to be a censuring force. Crain states that when “saying why a book is or isn’t any good, the critic is free to choose which standards to apply—to judge the standards of judgment, as it were—and, if necessary, to invent an altogether new one”. One thing worth adding to this is the need to let the reader in on the criteria of “the standards of judgement”. Effectively, the critic’s use is to act as mediator between the public and the work of art; to bridge the audience to the piece in question instead of alienating us from it or ingratiating us to it.

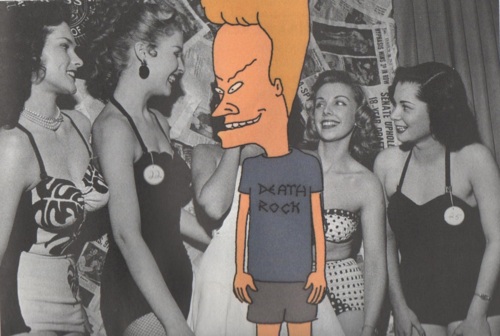

It seems pointless, joyless, as well as unkind, for critics to be categorically “anti” whatever it is that they are reviewing, like the ageist review my friend cited. Besides the question of etiquette, if a critic does not extend him or herself beyond criticizing the subject, they are not much different from Beavis and Butthead sitting on a couch, insulting and chuckling at everything that appears on the TV screen. On Terri Gross’s Fresh Air interview with Mike Judge, creator of “Beavis and Butthead”, they consider the least compelling kind of critic: one who uses “condescension as a way of life, as a sport”. Beavis and Butthead are perpetually opinionated, but rarely emerge from their parents’ basement long enough to make themselves vulnerable to criticism. A critic is free to find gaps and flaws, but it is shiftless to slag something off, then decline offering up an alternative or chance at betterment. (Side note, my critical review of “Beavis and Butthead” is that it is perfect.)

Bill Clinton’s speech at the Democratic National Convention was, in part, so well received because he used the platform to be a partial commentator. Instead of just reading off a puff-piece about his party, he acted as critic of the current political climate—giving it moderate to rallying reviews—and as critic of the potential socio-economic climate to come under Romney—giving it sour to horrible reviews. One of his “standards of judgement”, to borrow Crain’s phrase, included backing up his points with apparent facts and statistics. Sure, his view is slanted, but bipartisan listeners seemed to agree that his conversational tone carried weight because it remained active and involved. Just about every criticism he made of either party was qualified with context, then balanced with a pretty viable solution. It made me wish he had a regular radio show to break down what was going on in congress year-round. Hell, if he could just make one episode to re-explain what congress is to me once and for all. It was a relief for someone besides the policy-makers explicitly in question to explain their policy-making.

And this is where the critic should come in, whether it’s a commentator on a YouTube video, or a published writer in the New York Times Book Review. Why would we implicitly put our trust in the artist/writer/politician him/herself? Sure the artist’s creative intentions are something to consider and cherish, but when these get too lofty, which they can, the critic is free and welcome to jump in, mediate, and clarify.