Brock Enright

Brock EnrightDetail, Poppyseeds On A Rusted Box With A Cat Whisker, 2013

Wood, poppy seeds, cat whisker, motor

3 1/2 x 30 x 36 inches

Image courtesy of the artist and Kate Werble Gallery, New York

Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

I had two dreams after seeing “Verdigris,” Brock Enright’s solo show at Kate Werble Gallery this summer. The first was about Poppy Seeds on a Rusted Box with Cat Whisker (2013). This piece was exactly as the title described, 3 ½ inches tall by 30 by 36 inches, filled to the brim with poppy seeds. The outside of the box was made of wood, which was treated with an iron pigment that rusted when sprayed with water, then coated in resin. The poppy seeds inside looked like cat litter. In the middle of the box was a very small, conical gold inset, with a lone cat whisker sticking out of it, completely vertical, and rotating at high speed, powered by a hidden motor. In the dream, I leaned my face into the piece, alarmingly close, and brought my cheek up to the whirling whisker. At the moment it swept my face I woke up.

The second dream involved Verdigris (2013), a pair of Doritos intentionally yonic in their arrangement and hung at vagina-height on the wall, treated with copper pigment eroded into the verdigris of the title from being spraying with water, then coated with resin. In the dream, Brock sold me half of the piece, which I held gingerly in my right hand, and then inadvertently crushed, though the resin coating did not allow the little Dorito pieces to separate. Take me, Freud, I’m yours.

Verdigris, 2013

Doritos, copper pigment

3 x 4 1/2 x 2 inches

Image courtesy of the artist and Kate Werble Gallery, New York

Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

Part of what I long for when I look at art is for a somatic experience: the image enters the eye, activating inner space; the body responds. When I look at El Greco’s Vincenzo Anastagi (1571-1576) at the Frick Collection from the other end of the East Gallery, I want to feel, at a massive distance, the after-image of his thick façade burning a hole in my memory. At Pocket Utopia this summer, I saw Richard Tuttle’s curated selection of prints by Johann Christian Reinhart. As my eyes soared across the picture-plane of these impossibly detailed etchings of idyllic landscapes, I heard, deep in my mind, the wind rustle the infinitesimally small leaves of the trees. When I surreptitiously kicked the melting glacial fragments of Olafur Eliasson’s Your waste of time (2013) on a hot July afternoon, I did it to feel the scale, solidity and coldness of its mother, very far away.

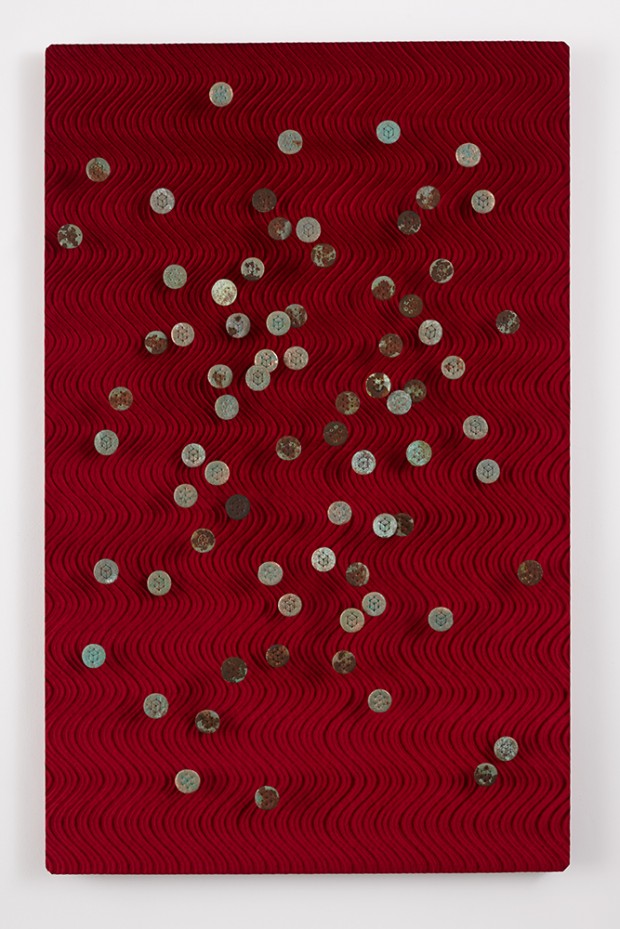

Enright’s work pulsed through me in such a way. The show was one of four summer exhibitions up for discussion at the final session of the Review Panel back in June. It was difficult to persuade my fellow panelists, Ken Johnson and Eva Diaz, of how moved I had felt by the work, how it had entered my dreams. Eva, certainly, as an art historian, was cerebrally tickled by the work and the legacy of its creator—Enright made his name around ten years ago by starting a boutique pre-planned kidnapping service, kidnapping wealthy patrons with a fetish for relinquishing control. (Enright later expanded his service into Videogames Adventure Services, constructing entire reality games for the highest bidder.) That super-cerebral paranoia, that all-permeating low-level anxiety that fuels this kind of practice seeped its way into “Verdigris.” Nervous Spoon, Meditating Rain (2013), a contorted spoon attached to a little motor, rattling in the corner, suffused the gallery with a tinny, rhythmical grating, at once peaceful and horrifying. Cubes in Motion (2013) showcased a variety of Ritz crackers, rusted and resin’d like the Dorito yoni, emerging on brass pins from a garish, wavy red fabric canvas. The holes in the Ritz crackers had been threaded to create, or perhaps reveal, a sketch of a cube, tessellated on the surface of Keraunographic Entrance (2013), an egg tempera painting on paper mounted on wood panel on the opposite wall. Apparently, Enright stockpiles thousands of Ritz crackers, hand-selecting the most perfect ones for his work, threading them each with this infinite pattern like a secret code. Eyes darting between walls, in my mind I saw the pattern connecting the pieces, crawling along the floor and up my arms, everywhere; the pseudo-schizophrenic nature of Enright’s practice enters the skin.

Detail, Cubes In Motion, 2013

Ritz crackers, thread, fabric, copper, brass

65 x 41 x 7 inches

Image courtesy of the artist and Kate Werble Gallery, New York

Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein

Many objects in the show are tinged with rusted copper, turning the verdigris of the show’s title. I thought a lot about verdigris, a color that only exists with a kind of alchemy, a green by-product of rusted brass or copper turned Lady Liberty iconic. For those uninterested in the history of materials, it may seem strange that some colors cannot exist divorced from their material wellspring. Mummy Brown, for example, is a brown obtained from the ground up fragments of Egyptian mummies. It can only be found in museum-entombed paintings now. Lapis lazuli pigment is the color of lapis lazuli stones, crushed up and refined a number of times. As the stone becomes rarer so does the color.

This summer, during a walk around the block on my lunch break, I discovered Kremer Pigments Inc., a family-run operation devoted to discovering and redeveloping painting pigment. I went in and asked the nice lady, Erin, if they stocked any Lapis Lazuli. Erin showed me a number of different grades, ranging from $58 to $300 for five grams—lapis lazuli is often found streaked with granite, so a cheaper Lapis pigment will have more granite and be less brilliantly blue. She then showed me a pigment that looked exactly like Lapis Lazuli, but which was a lot cheaper. This made sense for the visually minded, but for the alchemists among us, those interested in the pneumatic quality of the parts of an object, breathing life into its whole, the purest Lapis seemed key. I was reminded of the Byzantine icons in cathedrals across Europe, and the chanting and incense that their creators believed gave them life. Sure enough, I was informed that the people who purchase the authentic Lapis pigment are more often than not monks who paint religious icons. They enter the store in long robes, heavily bearded, sometimes with large medallions around their necks. I asked Erin about the preference of Buddhist monk patrons, and she told me that hers mostly, predictably, prefer gold, but weatherproofed, which they use to paint the outside of their temples. This weatherproof gold is around $100 for ten grams. An uncanny feeling, to unearth the price tag of a moment of spiritual opulence.

I asked Erin if the Lapis Lazuli was the most expensive pigment they had in the store. She shook her head. Tyrian Purple, obtained by scraping the inside of the shell of a certain sea snail, and costs $935 for 1/4 of a gram. The purple mist just stuck to the inner surface of the jar. Only museums ordered it, and then only to do research. In Byzantium, Tyrian Purple production—a very expensive process, if one considers the twelve thousand snails required to color just the trim of a garment—was subsidized by the imperial court, and the cloth was reserved for imperial use only. Thus the Porphyrogénnētos, the Byzantine son or daughter of the reigning emperor, was (to translate the honorific) “born in the purple.” Later research revealed to me that “the purple” of this phrase might also havereferred to the Byzantine imperial birthing chamber, or Porphýra: a pavilion of the Great Palace of Constantinople walled, floored and ceilinged in a veneer of “Imperial Porphyry,” a deep purple version of the reddish rock, flecked with white.

L to R: Jung Hee Choi, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, voices; Naren Budhkar, tabla.

Photo: Jung Hee Choi. Copyright © Jung Hee Choi 2012

I opened this summer with a trip to Dream House, a magenta birthing chamber of a different kind. Dream House, for the uninitiated, is La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s sound and light environment, situated in a third-floor Tribeca loft. The concept of a Dream House was conceived in 1962 by La Monte and Marian; the first public sound and light environment was opened in 1969 at Galerie Heiner Friedrich. Though there have been many more Dream House installations in museums and galleries in Europe and America since then, this particular incarnation has been operational almost perennially since 1993. The entire room is flooded with magenta light, a trademark color of Zazeela’s light-artistry. Dream House, during its September to June season, is open from Thursday to Saturday, 2pm to midnight, but I was there at the beginning of June for a very special suite of performances by the Just Alap Raga Ensemble. La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, and Jung Hee Choi, accompanied by Naren Budhkar on the tabla—specifically The Tamburas of Pandit Pran Nath from the Just Dreams recording—sang an alap for hours to an audience that had been tuned to the room, just prior, by a drone of tamburas emanating from suspended speakers for forty-five minutes.

La Monte is seventy-seven years old now; he has been perfecting the art of the raga for forty-three uninterrupted years, beginning with his and Marian’s twenty-six year apprenticeship to famed raga singer Pandit Pran Nath. There is no way to describe the sensation of melting between the notes of this unspeakably refined raga sound, booming from the frail body of this founder of Minimalism. It truly felt like a kind of rebirth, into a body of light in a resurrection of light.

I had the pleasure of meeting La Monte after the show through a mutual friend. We chatted for a while, and then La Monte told us that this sort of music brings one to a higher vibration: if we immediately stopped talking we might stay in that vibration for as long as possible. We all sat in silence for several minutes, our cells humming and vibrating the color purple—so close to white!—before departing.

✖