I met Ellie Ga in 2009 in Sicily. We both visited the ancient temples at Agrigento on the same afternoon, and while waiting for the train back to Palermo, we shared a cigarette. She explained that she had recently spent five months as an artist-in-residence onboard a research boat locked in the ice at the North Pole. She had come to Palermo to begin work on a multimedia essay based on the experience. We became friends. I was living in an old hotel at the time, trying to write an essay about medieval tunnels under the city, and on days when I was stuck, I’d go find Ellie. We would walk through the dirty, baroque city or take excursions to see ruins in the hills.

I became familiar with her work and saw an artist who was experimenting with narrative in ways I’d never seen before. Her essays, which she performed before live audiences, were part field dispatch, part artist’s notebook, part home-movie, part poem. She employed an array of media, ranging from photographic stills and video footage, to annotated maps and sculptural casts. I thought of her as a kind of adventurer-archivist, who had a deep connection to antiquity and mythology and a desire to preserve the ephemera of the past. She had a delicate finger on themes of language, memory, translation and the other quiet, subterranean ways we make sense of the world.

I first saw The Fortunetellers, as she ultimately titled the essay about the Arctic, at The Kitchen in New York. Standing at the front of the dark theater, Ellie toggled between video footage and transparencies of photographs, sketches, maps and diary entries which were projected from a light-box. You could see shadows of her hands against the light as she laid down each image. She delivered a monologue, which was interspersed with recordings of conversations with the crew, and sounds of the Arctic—the groan of polar ice, the squeak of an anchor being lowered. The narrative had the shape of a boomerang: she’d begin in the surreal day-to-day minutiae of polar life, draw tangential connections outwards to mythology, archaeology and philosophy, then return again to the ice. It felt like a haunted, dream-version of those lectures that Victorian explorers would deliver upon returning from the edges of the world.

The Fortunetellers was the first installment in a three-part series, each taking the Arctic as its point of departure. The second and most recent installment explores the symbol of the lighthouse, which was the first source of light the crew saw as the boat broke free from the ice. Ellie traced the latinate etymology of lighthouse—il pharo, le phare—back to the island of Pharos in Egypt, where the ruin of the ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria lies at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea. Ellie learned to scuba dive and moved to Alexandria where she enrolled in the Maritime Archaeology Program at Alexandria University and spent five months exploring the submerged ruins.

Her work has been exhibited internationally, most recently at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark; Grand Arts in Kansas City, MO and the New Museum in New York. She is the recent recipient of a three-year grant from the Swedish Research Council. She is currently developing a new performance essay, Eureka, a lighthouse play, with The Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) which will be presented in October of 2014. A video based on her research in Alexandria called Four Thousand Blocks is currently on exhibition at Bureau Gallery in New York. Not long ago, I sat down with Ellie in London, where she lives with her partner Ben and her cat Roy, and discussed her work.

—Will Hunt

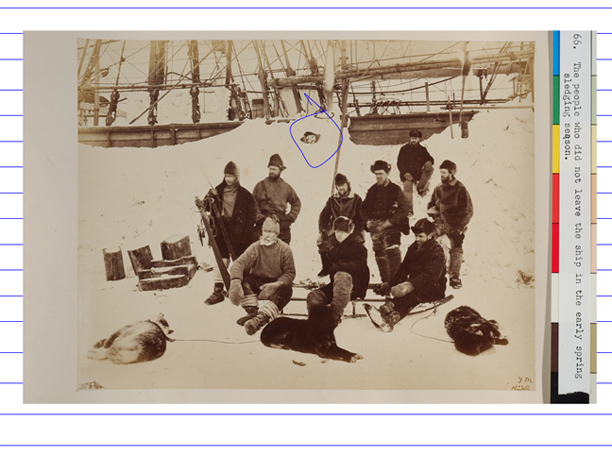

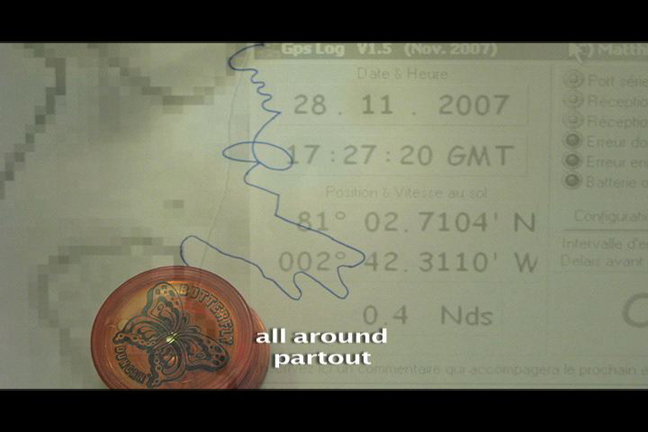

- Tara expedition 2007-2008

- Tara expedition 2007-2008

- The Fortunetellers (still), 2009, RISO—Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Palermo, Italy

- Classification of a Spit Stain, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009. Hardcover, 64 pages

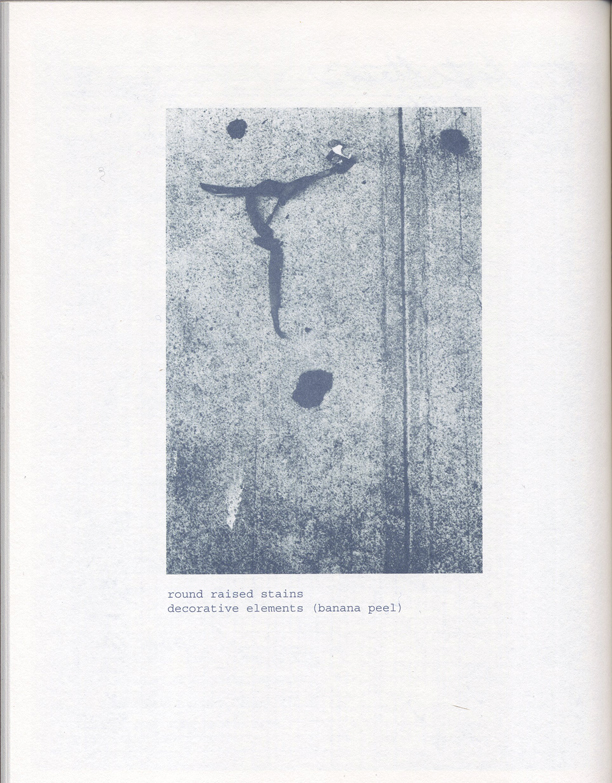

- Classification of a Spit Stain, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009. Hardcover, page 3

- Classification of a Spit Stain, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009. Hardcover, page 5

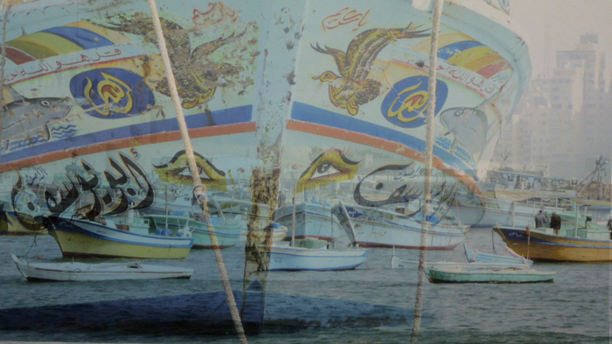

- Four Thousand Blocks (still), 2013-14, three-channel video, sound

- Catalogue of the Lost, 2007, performance

- Four Thousand Blocks (still), 2013-14

- The Yo-Yo Lecture (still), 2008, video, sound 11 minutes

- Lighthouse card , from The Deck of Tara

- Reading the Deck of Tara, performance still, Bureau, NY

A selection of images from her works can be viewed in the slideshow above.

An excerpt from the film At the Beginning North Was Here (2010) can be viewed below.

Four Thousand Blocks will be on exhibition from March 23rd to April 27th at Bureau, 178 Norfolk Street, New York, NY.

Will Hunt: Four Thousand Blocks, the latest installment based on your research on the Pharos Lighthouse of Alexandria, resembles a kind of multimedia archive: sound recordings, photographs, film, interviews, documents, diary entries and sketches. It almost feels like a documentary. Do you think of yourself as a documentarian?

Ellie Ga: My process almost always begins with a camera, but I’m not really a photographer. I have always been more interested in the noise around a photograph. All of the subliminal things happening around the moment of photographing that don’t make it into the image. Which is why I sketch, I record audio, I make videos, I collect documents, I make sculptural casts. But what I’m doing is not reportage. More than a journalist or a documentarian, I work in ephemera, in discarded pieces of the past. On some level, I think I play the role of archivist. One of my first fully realized projects was Classification of a Spit Stain, which was a pseudo-classification of the stains and detritus found on city sidewalks. I read everything I could about garbology, where garbage is analyzed to determine human waste patterns, and spent several years photographing different kinds of stains I found on the street. I invented a classification system for the stains and published my first artist’s book: an archive of the spit stains.

WH: That makes me think of Delillo’s Underworld, which is all about waste, “the secret history, the underhistory,” as he calls it. It’s about sorting through all the world’s discarded, overlooked knowledge.

EG: You can draw connections between and bring order to all these discarded pieces of the world and create a narrative. After the spit stains project, I worked in an archive at the New York’s Explorers Club, where I spent an eighteen-month residency studying the ephemera of Arctic documentarians. My first live narrative performance, The Catalogue of the Lost (and other revelations) was based on this residency. The narrative begins with a search to find a misplaced photograph in the archives and evolves into an essay about lost people, places, concepts and species in the history of polar expeditions. The archives include personal letters, early Arctic photographs and bookworm-eaten books. So the path of a bookworm becomes the central metaphor for the way an expedition reveals itself through the changes it makes to the lands, waters and people it encounters, like the bookworm eating its way through a book and leaving a trace of its path. This metaphor became a way to interweave things as seemingly disparate as the archivist’s discarded papers clips and early explorer’s attempts at photography. At the end of my residency, I delivered this live narrative for members of the Explorer’s Club who had been wondering what I’d been doing burrowing through the archives for a year and a half.

WH: So that was the first time you presented your work in the form of a performance essay, which is now a central part of what you do. How did you arrive at that form?

EG: There seems to be a proliferation of artists today working with the ‘performance lecture’. I use the term ‘essay’ rather than ‘lecture’ because it speaks more to the literary than the didactic. I’m drawn to the form because of its agility. It allows me to tell narratives that expand and contract between public and private histories, or micro and macro experiences. I guess it all began with this moment in graduate school when my advisor came into my studio and said, “Listen, for the rest of the semester I don’t want you to make any art. Because talking to you about your work is much more interesting than the work itself.” She insisted I just focus on the final assignment for the course: to curate a hypothetical show of the influences on my work. So I constructed a spoken illustrated essay called The Window Was. The images were taken from a range of subjects: banal snapshots of empty European cities taken by a friend’s father who was a doctor in the Third Reich, paintings by Vermeer and Philip Guston, photographs by Boris Mikhailov, texts from Benjamin’s The Arcades Project, the abbreviated folders at the New York Public Library’s picture collection, a summer spent in Belgrade.

WH: Emerson once compared the essay to a panharmonicon, which was an instrument with many different instruments folded into it. You turned a crank and it played a whole orchestra: flutes, drums, trumpets, cymbals, trombones, a triangle, clarinets, violins. In the essay form, like the panharmonicon, “everything was admissible—philosophy, ethics, divinity, criticism, poetry, humor, fun, mimicry, anecdote, jokes, ventriloquism.” As someone who writes textual essays, I’ve always been a little jealous of your performance essays, because you come so much closer to the ideal of the panharmonicon. They allow you to create freer, more synaptic narratives, with turns that would feel forced on the page.

EG: Well, I think that’s probably true: the mode of live performance allows a wider berth of narrative drift because as long as you can keep an audience engaged, you can take them through many branches of thought. It’s more challenging to record and present these kinds of associative narratives in the gallery context as the gallery viewer can stay for five minutes and leave. Whereas in my life performances, the shifting between media—photography, video, audio recording, drawings, live readings—allows me to create the synaptic narrative you mentioned. And I like the term synaptic for these performances because they reflect the shape and texture of memory. When we recall an experience, we draw a kind of fractal, non-linear map of smells, images, sounds, sensations, tastes. Somehow performance, more than simply text on a page, allows you to replicate all of these tenuous leaps.

WH: One writer I love who is a master of the synaptic narrative is W.G. Sebald— at one point in Rings of Saturn, where he is constantly dipping into seemingly disparate, but actually connected, moments in history, he compares his mind to “the paper universe.” I know he’s a big influence for you. Who are some of your other influences in this form?

EG: Sebald was someone I had to stop reading in grad school because he was becoming too strong of an influence. Beyond him, it’s a lot of narrative works that confound distinctions between documentary and fiction, private and public histories, writing and visual inscriptions. Some that come to mind are: Sven Lundqvist’s Exterminate All the Brutes, Jacob Bronowski’s filmic-essays in The Ascent of Man, Patrick Keiller’s Robinson series have been important to me. Agnes Varda’s films, too, especially The Gleaners and I, where she travels through France examining various interpretations on gleaning—the act of collecting what has been discarded.

WH: There’s a moment I’ve always loved in The Gleaners and I, where Varda turns the camera on her own aging hands as she’s driving the car, bringing out the metaphor of herself, the artist, as a gleaner. That kind of critical self-reflection on your role as an artist is something I’ve heard you talk about before, especially regarding your work on the research boat at the North Pole.

EG: Tara was a polar research schooner which was locked in the polar ice for two years. For what ended up being the last five months of the expedition, I was invited along as the ship’s artist-in-residence. Our daily life on the ship revolved around survival and scientific research and I was first and foremost a crewmember. Our life was regimented, we had our weekly communal tasks: one week breaking ice and gathering snow for drinking water, another week cooking, another week cleaning. Every member of the crew—there were ten of us—was there to fulfill a very specific duty: two scientists, the chief, the captain, the cook, the doctor, the journalist, a mechanic, a carpenter/polar guide and myself. As an artist, I was an aberration, the only one who had no ‘practical’ role. The other crew members would watch me take video recordings of the ice cracking at night or hear me talking into my audio recorder, and wonder what I was doing and what purpose I served. I realized that the only way to gain social acceptance—which was crucial to survival in such a high-pressure environment—was to make artwork for the crew. My platform became the Thursday night lecture series. On Thursday nights we’d entertain each other with presentations and the chief would bring out some whiskey and chocolates. The lectures covered a wide range, from pictures of vacations to powerpoints about the science being done onboard. I used this weekly ritual as a way to examine and communicate how I interpreted the surreal minutiae of our life. For example, my first lecture was about the etymology of the word yo-yo, which was both a toy we played with on board, and a bathymetric instrument used to measure the salinity and temperature of the ocean. Twice a week we cut a hole in the ice and dropped the instrument underwater, like a yo-yo. And then I thought of our drift, north, south, east, west, as replicating the yo-yo. Later on, after we got out of the ice, these presentations I was doing on the boat became the narrative foil for the performance The Fortunetellers.

WH: I love that. A boat locked in polar ice is a closed universe, where all daily minutiae take on a deeper significance. It’s the perfect terrain for an artist.

EG: Absolutely. The Arctic was a vacuum, untouched by any external force. Everything we did up there echoed in on itself, like part of some myth. Ultimately, my series of performances on the boat revolved around the metaphor of fortunetelling and our relationship to the future. See, as we drifted in the frozen Arctic Ocean, we had no control over the boat’s movement, which meant we had no idea when we would return home. Everyday, we’d wake up wondering if we’d break out of the ice in a matter of hours or if we’d continue drifting for months. Our day-to-day lives were shot-through with this anxiety about the future, from the cook, who would become stricter with food rations, to my own manic fear that we’d get out of the ice too soon for me to make anything substantial from the experience. We had a betting pool, a ritual of trying to predict the future. At the same time, our whole reason for being in the Arctic was to collect data about climate change. Which is to say, the climatologists were out there doing their own brand of fortunetelling, trying to make long-term climate prognostications on the future of the planet. So for one of the performance essays I made based on my time on the boat, Reading the Deck of Tara, I used fortunetelling as a narrative device. I created a bespoke deck of cards from my photographs of the Arctic expedition. Each card had a name and associated concept, and in the manner of a fortune-teller, I would welcome visitors to sit across from me and choose a card. I would then weave a narrative based on the connections between the cards.

WH: The ultimate synaptic narrative.

EG: The narrative was never the same twice, incorporating my interaction with the sitter as well as their reaction to the work. Walter Benjamin writes that half the art of storytelling is to keep a story from explaining itself as one reproduces it. The piece allowed me to scrutinize how the reshuffling of narrative events can present research in a form that becomes art, through the context of each unique telling.

WH: This idea of a narrative not being fixed, of being mutable, and emerging slowly in shifting layers, is something I see a lot in your work.

EG: I think that comes from my preoccupation with mythology. A myth is a story that is never fixed: by definition it is protean, perpetually re-tellable. It conflates personal and historical memory, making everything mutable and abstracted. A myth is made up of all of these fine layers, accrued over so many different retellings. In my essays, I try to use the same layering. When I perform, I use a lightbox, which is then projected onto a screen before the audience. Over the course of the show, I lay down material—photographs, drawings, documents—on the lightbox and then slowly obscure and reveal aspects of the story as it builds. On some level, I am trying to emulate the shadowiness and mutability of myth.

WH: I remember a few years ago we watched a documentary together on the “Archimedes Palimpsest,” about a lost 10th century copy of a text by the ancient Greek scholar, which had been overwritten on the same page by 13th century scholars, thereby destroying the text, but also securing its preservation. I know this symbol of a palimpsest became a big part of all of your work, but it is particularly strong in your latest pieces on the Pharos Lighthouse in Alexandria.

EG: My work about the lighthouse in Egypt goes back to the moment on the boat in the Arctic when we were exiting the ice and the first light we saw after months of darkness was the light emanating from a lighthouse. That lighthouse—it was off the coast of Svalbard—became a metaphor for me of the future, of origins and destinations. And so I followed this symbol of the lighthouse back to its roots, the Latinate words of il faro in Italian and le phare in French, which brought me back to the Pharos Lighthouse in Egypt, which was sort of the ur-lighthouse. It was one of the ancient wonders of the world and the only one besides the Pyramids at Giza to last until the modern era, until it was finally destroyed in the 14th century by a series of earthquakes. Now the lighthouse is a ruin, submerged in the seabed off the coast of Alexandria. So in order to really get at the base of this symbol, I learned how to scuba dive, enrolled in the Marine Archaeology Program at Alexandria University, and spent five months in Egypt, exploring the ruins of the lighthouse, and interviewing the archaeologists who had worked underwater.

And yes, there are layers everywhere in this narrative. The program was postponed because of the revolution in 2011 and I arrived in the months leading up to the presidential elections of 2012. It was a bit bizarre reconciling the amount of time I spent planning the project with the urgent contemporary moment unfolding in Egypt when I arrived. Friends and colleagues back home were urgent to hear what I had to say about the political situation in Egypt and I often found myself feeling like an anachronism: being in Egypt in 2012 and researching an ancient Greek construction. At the same time, the lighthouse of Alexandria is a symbol of the overlap between civilizations. It was designed by the Ancient Greeks using Ancient Egyptian materials and building techniques, then repaired and converted into a minaret during the Middle Ages. And I think it is particularly important nowadays to engage the historical richness of these overlaps.

WH: You use these layers as a storytelling device beautifully in Four Thousand Blocks—the video that’s now up at Bureau. It’s a three-channel video, so really three videos playing side-by-side. The center feed is your lightbox, where you are laying down photographs and transparencies and other ephemera you collected in Alexandria; on the left, shadowy footage of you in the darkroom; on the right, continuous footage of your hand moving over a typesetter’s case. So the whole narrative has this feeling of layered action happening synchronously.

EG: That’s good to hear, because that’s what I had in mind. The Four Thousand Blocks essay—recorded this time, rather than performed—is a lot about translation, which, in my work, is the most ubiquitous form of palimpsest. While exploring the ruins of Alexandria, I learned that the island where the structure once stood had been the site of a great act of translation. It was called the Septuagint: 70 Hebrew scholars were invited to the island, locked into 70 separate rooms, and asked to translate the Bible from Hebrew into the Greek of the day. Some legends says the scholars were forced, others say they did it of their own accord. The point was that each worked in their separate rooms on the island and had to emerge with the same exact translation. This mythical act of translation becomes a kind of backdrop through which I explore how various ideas and symbols have traveled from ancient Egypt, to ancient Greece, to modern Egypt.

The legend of the Egyptian god Thoth in Plato’s Phaedrus becomes another face of this theme of translation. Thoth presents all his inventions for humankind to the King of Egypt or approval, his most prized invention being writing, because it will aid memory. And the King says no, it will give humankind the gift of forgetting. It’s actually Socrates relaying the story in Phaedrus—and that’s especially funny if you think how Socrates is not known to have written anything down. In Derrida’s Plato’s Pharmacy, Greek text of the above dialogue the word pharmakon appears as having two meanings: poison and salve. So the salve to fight off forgetting, or a poison to the memory depending on whether you see it: through Toth or the King’s eyes. This is the same kind of dichotomy that surrounded photography when it was first invented: is it a black or white magic? Will it serve, as a map or a screen to understanding the world. These themes are present throughout the video’s narrative.

WH: One of the things I love in an artist or writer is when you are able to lay out all of their works and find that the edges fit together, each piece another facet of a cohesive imagined universe. I’m thinking of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Your work does the same. Each series of works bleeds into the next, as though everything were part of a single cosmology. What’s the next chapter in the story?

EG: The series of works about the Arctic, The Fortunetellers, and the works I’m finishing up about the Lighthouse, which collectively I call Square, Octagon, Circle, will be followed by a third series based around the theme of the message in a bottle. When we were on the boat, as we were breaking free from the ice, we all cast messages-in-bottles overboard. So I’m exploring the message-in-a-bottle as a form of communication and as a way to measure oceanic drift. And then we’ll drift from there.

✖