Part II of this essay, written after Sunday’s show, can be found here.

✖

Every year for as long as I can remember, I’ve heard it proclaimed as though being discovered anew: the Oscars are irrelevant. It’s an easy claim to make, and one I made for a long time. What are the Academy Awards if not an industry’s masturbatory celebration of its own greatness, at great length and great expense, an event which is always boring and almost never celebrates great films? Of the last twenty Best Picture winners, only seven are even decent movies[1], while nine are plain stupid[2]. Crash, 2005’s winner, should be shortlisted for worst Hollywood film of the last decade.

Of course, the Academy Awards are anything but irrelevant to the film industry. The famous “Oscar Bump,” which makes ticket sales explode, is the main reason most “Oscar contenders” are released in November and December. Being nominated for Best Picture means an average of $20 million in extra ticket sales before the ceremony takes place, with another $5 million after the awards if you lose. Winners can expect another bump of $14 or $15 million. (And that’s to say nothing of DVD and Blu-ray sales.) Best Actresses and Actors can expect a 20% pay raise, as, no doubt, can cinematographers, make-up artists, etc. The Oscars are major TV business, too, providing a flagging ABC with its only surefire yearly hit, usually garnering ratings on par with the State of the Union address. As with presidential campaigns for political reporters, it periodically makes entertainment reporting and film criticism that much easier and more lucrative—in short, the Academy Awards make a lot of people a lot of money. Oscar is a job creator.

But ‘financially lucrative, artistically irrelevant’ doesn’t really get to the heart of the matter. The Oscars are the moment when the film industry publicly avows which films it believes are its most lasting contribution to the culture. The Academy, rather than representing anything like the film-labor pool, let alone the demographic make up of America at large, is 94% white, 77% male and 86% over the age of 50. The film industry’s powerbase, like all industries in America, is old, white and male.

This, ironically, makes the Oscars more valuable as an analytic tool, not less. The members of the Academy are the bosses, the studio heads, the good old boys, producers and owners who perpetuate Hollywood hegemony and most benefit from its reification and appearance as more than just a consumer product (while guaranteeing that this reification lends itself to cinema’s continued commodification). While the workers who produce Hollywood cinema may be interested in creating art, it is their bosses (who control the production process, who have mechanized and managerialized it so that the thousands who want to make film art can be exploited toward the production of endless Hollywood schlock) who get to nominate and name the Best Pictures. An industry wide sample might actually capture the opinions of some artists, but the Academy promises to only reflect the opinions of the moneyed interests. The Oscars are valuable because they show us how the industry—as embodied in its owners—likes to imagine itself.

Last year’s Oscar ceremonies, then, revealed an industry going through an identity crisis. The theme seemed to be “remember when movies were meaningful?” In a pre-taped segment actors and directors wistfully described the moment they fell in love with movies, Billy Crystal hosted with the grim boredom of the same old shit nine times around, and Kodak, famous sponsors of the Academy Awards’ theater, had declared bankruptcy just weeks before the ceremony. The whole thing felt like one long In Memoriam tribute. The films celebrated last year, too, showed that nostalgia for cinema had become the mode of critic and producer alike: Hugo, The Artist, Midnight in Paris… Outside the ex-Kodak’s hollow halls, the proliferation of sequels, reboots, remakes and franchise films revealed a ‘creative’ industry which couldn’t even make up new images as it lay belly up at the trough of profit, which, despite the loud legal protestations of the anti-piracy goons, was as full in 2011 as it had ever been.

Last year’s program copped to the death of Hollywood cinema-as-art. All that was left was looking backward over a once-hallowed institution and weeping over the corpse. This year, though, the tears have dried. What we see instead is a clear vision of the utility of cinema. The 85th Academy Awards, like no show before it, will elevate films that are openly ideological, weaponized tools of the state.

✖

2012 was a year of highly ideological cinema. Act of Valor, made in close collaboration with the Navy and starring real Navy Seals, and Red Dawn, which produced a wave of anti-Asian xenophobia, were the most naked and vulgar examples of the trend. The Dark Knight Rises featured villainous revolutionaries taking over Manhattan, and, in production in 2011, was filming protest scenes at the Stock Exchange while Occupy Wall Street was at peak strength five blocks away.

But the real heavy hitters, as far as the Academy Awards are concerned, sparked acrimonious political debate in major forums, playing a serious role in the cultural dialogue in a way film hasn’t for years. Django Unchained created a fierce debate about whether it was anti-racist or just liberal racism dressed up in slaveowner-killing clothes. I lean toward the latter: the film denies the agency of all the slaves who aren’t Django, who himself requires the inspiration and martyrdom of a white man to truly free himself. (It seems to me that Tarantino is less interested in these questions than discovering situations in which the morality of aesthetic depictions of violence cannot be questioned. From Kill Bill’s gang of wicked assassins to Death Proof’s leering murderer to Nazis to slave owners, Tarantino increasingly builds worlds in which he can splatter gallons of blood while maintaining a clear conscience for himself and his audience.)

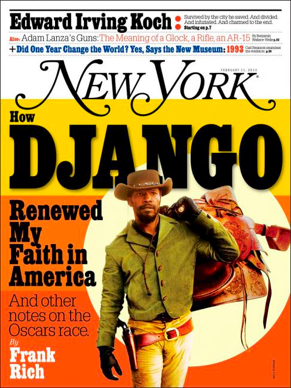

Wherever you come down on Django Unchained, the cover of New York magazine’s February 11th issue features a clear ideological deployment of the film. Circling a picture of Jamie Foxx as Django, the cover reads: “How Django Renewed My Faith in America/And other notes on the Oscar race.” If there is more direct evidence toward the point I’m trying to make, I can’t imagine it.

Lincoln, which garnered the most Oscar nominations this year, is, according to odds-makers in Vegas, the second most likely candidate for this year’s Best Picture. The film was written by Tony Kushner, who went on NPR and MSNBC to explicitly discuss how his Lincoln is based on Obama, and directed by Steven Spielberg, who donated $1 million to Barack Obama’s SuperPac. Both Kushner and Spielberg are up for Oscars for their work on Lincoln, which was made by Dreamworks. Jeffrey Katzenberger, CEO of Dreamworks-Animation, was Obama’s largest individual donor.

Lincoln’s drama centers around the backdoor-dealing and House-floor speechifying involved in winning Democratic votes to the Republican cause of the 13th amendment. Although beautifully crafted and occasionally enlivened by performances from Daniel Day-Lewis and James Spader, Lincoln is an incredibly boring movie—the climax of the film is the actual vote on the amendment, a ten minute scene of the House’s clerk reading out the names of representatives as they say ‘yea or ‘nay.’ Lincoln lacks either narrative or moral drama, instead pitting the insuperable (and supremely correct) Lincoln against a sea of unreliable and waffling allies, reactionary bigots and selfish politicians. The ending is foretold. Only Lincoln’s clever, legalistic political maneuvering can win the day—it makes up most of the film’s running time, and it often crawls.

Kushner’s script goes out of its way to stress Lincoln’s policies which, though distantly, mirror Obama’s. At a meeting with his cabinet Lincoln defends the Emancipation Proclamation as an extra-legal executive act that the people accepted implicitly by reelecting him. This is remarkably cynical on the part of Kushner. By having Lincoln make a full-throated defense of executive privilege around the Emancipation Proclamation (itself a cynical piece of politics which did not apply to the five slave states still in the Union), Lincoln implies that if not for executive privilege we would still have slavery. Some food for thought before you go slamming Obama’s extra-judicial killing and drone warfare. At Appomatox, he tells Ulysses Grant to treat the Confederacy with “liberality all around, not punishment, I don’t want that.” Indeed, we need to look forward, not back. Oh yeah, and in a late scene with Mary-Todd Lincoln, he expresses his desire to travel to “the Holy Land…Jerusalem, where David and Solomon walked, I dream of walking in that ancient city.”[3]

Of course, even without the Obama comparisons, the celebration of Abraham Lincoln as “the man who ended slavery” has its own ideological functions. As Aaron Bady has argued masterfully, Lincoln is a work of revisionist history which greatly overvalues Abraham Lincoln, the white male congress and the 13th amendment’s role in overturning slavery, while writing out of the process radical abolitionists, black soldiers and escaped and rebelling slaves, nevermind your John Browns or Nat Turners. Ironic (or perhaps appropriate) that a film so clearly evoking Obama should so thoroughly silence black voices. If the Academy picks Lincoln, they’ll be voting for Obama’s anti-political vision of history: moderation, bipartisanship, true change emerging from above through wise presidential power.

✖

Entertainment is the United States’ second largest export, behind agricultural products. Movies (along with music, television and advertisements) play a vital role in both domestic ideological production and American global hegemony—or, as Harry Truman put it, when referring to cinema’s strategic value in westernizing occupied Japan and imbuing its citizens with a sense of guilt after the war, movies are important “ambassadors of goodwill.” No movie in recent memory plays out the role of cinema in global-political domination as clearly as this year’s odds-on-favorite to win best picture, Argo.

Based on a true story, the film centers around rakish CIA agent Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck, who also directed) as he rescues six US diplomats trapped in Iran in the midst of the Iranian Hostage Crisis. When revolutionaries stormed the US embassy, the six took off into the streets of Tehran and eventually found refuge at the Canadian Ambassador’s house. But as the crisis grows more severe, and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard start to hunt for the missing Americans, they need to be rescued, and quickly.

Enter Mendez, who decides the best way to save them is to enter Iran on his own, and leave with them in tow under the guise of being a Canadian film crew scouting out locations. To do so, his ‘film’ requires authenticity, and so he hires two Hollywood producers, buys a script, opens an office and holds press events.

In a brief opening storyboard-styled montage, the film, in its only moment of historical honesty, explains the role the CIA (and British MI6) had in the 1953 military coup that overthrew democratically elected Mohammed Mossadegh and installed the tyrannical Shah Reza Pahlavi to absolute power. Despite this clear explanation of Iranian distrust for the American state, the revolutionaries of 1979, who in turn overthrow Pahlavi, are pictured throughout the film as an inchoate, angry mob, bloodthirsty and pathologically (rather than, say, historically righteously) anti-American: the very first shot after the opening montage is of a group of Iranians burning an American flag.

That the CIA should be heroes of a crisis they helped produce clearly did not strike any of the filmmakers here as ironic: in fact, nothing about the film seemed to strike the filmmakers much at all. Argo is, save a few moments, completely cold, almost an exercise in narrative construction, with neither emotional depth nor any sort of perspective.

However, what the film lacks in emotional quality it makes up for in Hollywood mythmaking. As Richard Brody puts it, the film’s

“third-person naturalism conveys, above all, authority—an abstract

authority, not authorship; not the authority of a filmmaker or, for

that matter, of the historical sources, but of Hollywood. The crux of

the movie is Hollywood’s tribute to itself, Hollywood in the nation’s

service, Hollywood’s fantasy of coming to the rescue of Washington’s

reality.”

But how unrealistic is such a celebration of film’s deployment in international affairs? The state department has had a ‘motion picture’ section since 1916. All the Cold War presidents funded the US Information Agency to use film and television to propagandize against Soviet influence. Since 2001, the Pentagon has been a consultant on dozens of Hollywood films, and Hollywood filmmakers returned the favor, famously consulting with the Bush administration about potential terrorist attacks and possible solutions. As Tony Miller noted in Anti-Americanism and Popular Culture, USC’s “Institute for Creative Technologies uses military money and Hollywood directors to test out military technologies and narrative scenarios…There is even a ‘White House-Hollywood Committee’ to ensure coordination between the nations we engage and the messages we export.” Steven Spielberg is a recipient of the Department of Defense’s Medal for Distinguished Public Service.

We see this at work in the other Oscar contender about the real-life heroism of the CIA, Zero Dark Thirty. In preparing for the film, director Kathryn Bigelow and writer Mark Boal had access to high up White House officials (including John Brennan), classified documents and even a member of SEAL Team 6, access that was not available to members of Congress. The eagerness with which the Obama administration shared highly classified information for mass cinematic deployment—when revealing similar information to the public directly would have Obama’s DOJ trying to put you behind bars for life—says it all.

It seems to have paid off. In spite of a fierce debate over whether Bigelow’s film endorses torture (getting to the point where even Diane Feinstein got involved), this debate missed the broader ideological function of the film: to celebrate the CIA and the War on Terror, to cheer the killing of Bin Laden. Or, as Spencer Ackerman wrote, defending the film from its anti-torture detractors, its “ending scene makes viewers very, very proud to be American.” There was a time when Americans were proud that, no matter who the enemy, they were given a fair trial. That was never really true in practice, of course, but now we’re proud when an elite military squadron breaks into a compound halfway across the world and shoots an unarmed man in the face.

Still, Argo, a movie about the CIA making a movie to complete police actions, glorifies the role of Hollywood in international power projection much more directly then Zero Dark Thirty. It is also, as Brody writes, “a tribute not to Hollywood as it is but to an ideal of so-called adult drama that, supposedly, Hollywood doesn’t produce anymore.” When Argo wins Best Picture on Sunday, it will combine the nostalgic cinephilia of recent Academy Awards with the Academy’s new found appreciation for politically deployed cinema.

✖

The 85th Academy Awards will, as every year, be a boring, overlong, masturbatory tribute to mediocre cinema. For decades now, the Oscars have predominantly celebrated middle-brow films that embrace shallow evocations of gravitas over anything approaching creativity. One thing about owners, about the old, rich, white and powerful, is that when it comes to art they are deeply stupid: confusing seriousness with artistry, the emotive with the emotional, realism with profundity. But when it comes to control, strategy, and power, these confusions become assets, foundational aspects of bourgeois subjectivity, of obedience and self-ignorance.

This year’s Oscars, as usual, will have nothing to tell us about artistry. But they appear a particularly lucid reflection of the stake Hollywood’s owners have in the global power structure. When it comes to such issues, the Oscars are anything but irrelevant.

✖

[1] Unforgiven, Schindler’s List, Lord of the Rings: Return of the King, Million Dollar Baby, The Departed, No Country for Old Men, Hurt Locker. Some of these are much better than others.

[2] Forrest Gump, Braveheart, Titanic, Shakespeare in Love, American Beauty, Gladiator, A Beautiful Mind, Crash, Slumdog Millionaire. (I never saw The English Patient or The King’s Speech, but by many accounts they could be on this list.)

[3] The pastor who officiated at Lincoln’s funeral reported, long after the fact, that Mary-Todd Lincoln told him the president’s final words were about visiting Jerusalem: this is a very popular tale on the Christian Right. But the account is not considered credible. Why should Kushner choose to put these apocryphal words in Lincoln’s mouth? A few reasons suggest themselves…