Part I of this article, written before Sunday’s show, can be found here.

✖

Last night’s Oscars, beyond being the excruciatingly boring spectacle everyone knew they would be, had the added drawback of Seth MacFarlane’s despicable hosting. He came out in full force, referring to Django Unchained in his opening monologue as the “story of a man fighting to get back his woman subjected to unthinkable violence—or as Chris Brown and Rihanna call it, a date movie.” This year’s de rigeur parody song was “We Saw Your Boobs,” in which MacFarlane literally just listed actresses and the movies in which they appear topless or nude. Later in the night, Ted, the animated bear from MacFarlane’s hit film of the same name, threw out a series of anti-Semitic “jabs” at the Academy. There was a weird sexual insinuation about the nine-year-old Quvenzhané Wallis, a series of derogatory uses of the word “gay,” and boatloads of misogyny.

But it doesn’t take a three-and-a-half hour long Oscar ceremony to know that MacFarlane is a douchebag. As I argued here on Friday, what would be truly interesting about this year’s awards would be the relationship they revealed between the state and Hollywood cinema. This year’s crop of films, I argued, demonstrate a shift in the Academy’s celebrations of (usually mediocre) film-art toward an embrace of the utility of cinema as an ideological weapon. Hollywood films have been used as tools of the state almost since Hollywood’s birth, of course, but this year’s contenders—in particular Lincoln, Argo, Django Unchained and Zero Dark Thirty—were especially blatant.

Sunday afternoon, six hours before the start of the ceremony, this argument began to bear fruit. The official state department twitter account, @StateDept, tweeted out: “Good luck @BenAffleck and #Argo at the Oscars. Nice seeing @StateDept & our Foreign Service on the big screen.-JK” ‘JK’? That would be John Kerry.

After spending a week writing and thinking about the Oscars, I had little desire to actually watch the ceremony, so after a couple hours with it on in the background, I decided to shut it off and put my attention toward something, anything else. This turned out to be a mistake. I had to learn on Twitter, rather than seeing it live (and probably having an aneurysm), that Michelle Obama, via satellite from the White House, had appeared to give out the Best Picture award—to Argo.

Luckily, it was easy enough to find a video on the internet.

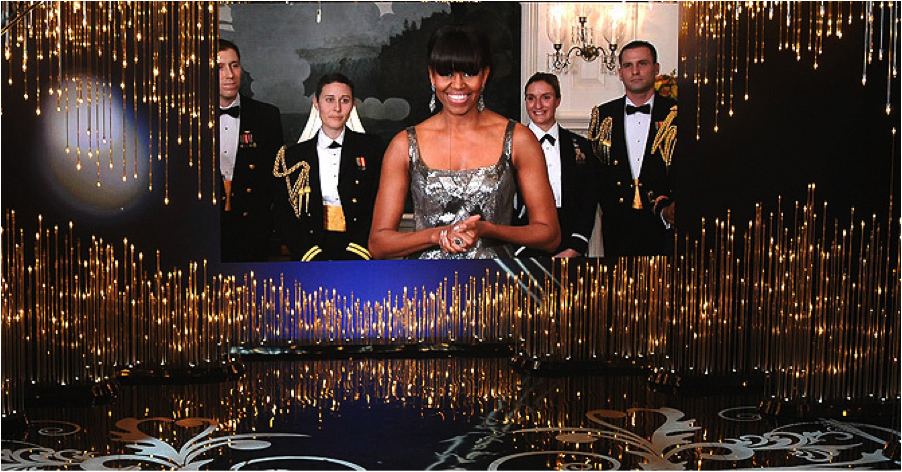

What a shimmering dystopian vision. High above the stage where America’s most famous and powerful entertainers are gathered, a huge screen appears, maybe 200 square feet in size, and on it, in a lovely evening gown, appears the President’s wife, flanked by a dozen or so soldiers in formal military dress. “Welcome to the White House everyone,” she begins. The banality of the statement that followed—about films that “lift our spirits, broaden our minds and transport us to places we can never imagine,” films that “made us laugh, made us weep and made us grip our armrests,” that “taught us that love can endure against all odds”—couldn’t obscure the presence of those soldiers behind her. Why were they there? What do she and her soldiers have to do with this awards ceremony, this trifle, this broadly acknowledged irrelevancy?

Michelle Obama is not the first White House resident to make an appearance at the Oscars. In 1941 FDR, by radio, delivered an address to the Awards. In it, he praised the film industry’s utility in spreading American values of freedom and democracy to the citizens of the totalitarian states of the Axis. Ronald Reagan addressed the 54th Academy Awards in 1981 in a pre-taped segment which, like Obama’s, was displayed via a huge screen. But Reagan was a former star and president of the Screen Actor’s Guild: he could, at least, make a claim to relevance for the ceremony.

More importantly, both Reagan and FDR’s appearances were direct manifestations of their presidential power. Though they paid tribute to the awards and to cinema, they appeared as presidents addressing the nation through the medium of the Oscars: They remained separate, above the proceedings. Michelle Obama’s role, however, was subordinate to the ceremony. She took part in it as a presenter like any other, an interchangeable (if particularly honored) part of the awards.

If Reagan and FDR openly discussed the part that film played in achieving state objectives, Obama spoke in boring, clichéd phrases about the artistry of film, eliding her purpose there as anything but a celebrant. By doing so, she (and what she represents, namely, the White House) achieved an equivalency between herself and the other Hollywood stars, who spoke in equally empty phrases toward the bland reification of cinema. Consequently, her rather frivolous appearance did much more to emphasize Hollywood’s political force than either of her predecessors’. Her role as “just one more member of the ceremony” reduced any difference between herself and Jack Nicholson or Mark Wahlberg to simply degree of celebrity, placing Hollywood and Washington into a symbolically horizontal continuum of power that includes but does not necessarily prioritize the state.

Thus the necessity of the soldiers behind her: while she may just be a part of the Oscars—in terms of spectacle, the Executive defers to Hollywood—the soldiers reassert the ultimate dominance of the White House. A deceptive deferral to the cultural sphere combined with a naked display of violent power: the stuff of tyrants.

Twitter is full of speculation that Michelle’s appearance, and her giving the award to Argo, hints toward administration intentions in Iran. We shall see. But I believe that evocations of Hollywood-Washington mutuality tend not to indicate direct corollaries between particular films and policy proscriptions, so much as generalized movements toward broader ideological goals. Argo is not about Iran so much as it is about lionizing the CIA, Lincoln is about presidential wisdom and decentering black history and struggle more than the 13th Amendment or Abraham Lincoln, etc. Not that all of these things aren’t present, of course, but the long production processes of films, not to mention the vagaries of the marketplace and public reaction, make them unreliable allies at best on individual issues. For example, it seems likely that Lincoln, among other things, was designed with Obama’s reelection in mind. Similarly, the Obama administration’s eager cooperation with the filmmakers behind Zero Dark Thirty reveals probable electoral intent. But both films were released after the election was over.

Therefore, in any analysis of a cultural product, it is that product’s deployment, more than any intention of its creators, that is most valuable. The huge public debate around Zero Dark Thirty, which foregrounded its propagandistic nature, effectively killed ZDT’s Best Picture chances (which, before the brouhaha, were seen as quite high) and also made it less functional as propaganda. Zero Dark Thirty is more nakedly ideological than Argo, but, as a result of the debate, people watching it are more likely to be wary of its implications. Of the two films celebrating the heroism of the CIA, then, Argo ends up the better tool.

✖

Argo is officially the Best Picture of 2012. For a more indepth analysis of the ideological processes inherent in Argo, I refer you to Nima Shirazi’s excellent take down of the film (http://www.wideasleepinamerica.com/2013/02/oscar-prints-the-legend-argo.html). Suffice it to say, it’s another mediocre Best Picture that will be all but forgotten in five years, celebrated in yet another impossibly boring ceremony. But what the 85th Oscars proved, beyond even my perverse expectations, is that the industry sees its greatest value to society as an advocate for the American state, a weapon in the fight for flagging American hegemony. The vulgar racism, sexism and homophobia of MacFarlane’s hosting were in fact the perfect complement to a year where manifestations of ideological domination were tantamount.

If there was any question of the role Hollywood plays in American power projection, it was crushed beneath the gaze of those soldiers. Standing silently in their formal wear behind their First Lady, honored, no doubt, to be a part of movie history, finding themselves in a place they couldn’t possibly have imagined when they enlisted, the soldiers smiled for the camera. They smiled and smiled and smiled.