It’s now a truism that “street style” photography is no longer a record of the spontaneous grace and/or preternatural weirdness of its subjects, but rather a sort of running advertorial for metropolitan belle-egoistes with disposable income and, apparently, disposable time. It takes a particularly skilled prey-cum-huntress/hunter to know how to be sought out in ordinary time. As fashion week begins, the playing field is leveled. Come the camera-seekers to the seedy outskirts of Milk Studios and Lincoln Center…come the idea-starved editorial assistants/freelancers/paid consultants to shoot them, skin them, and plate them—farm to table. Well, I rather liked this photograph on notvogue.com. What a marvelously succinct articulation of this bizarre seasonal hunt: prey meets prey, hunter meets hunter…but who will be eaten? Rarely is high drama so frighteningly banal.

—Uzoamaka Maduka

“…Speakers, in their panegyrics of the emperor, made this a leading theme: ‘Earth,’ they said, ‘is now producing not only her accustomed crops, not only gold mixed with other substances—she is teeming with a new kind of fertility! Wealth unsought by the gods!’ —and every other invention which eloquent sycophants could devise. They were confident of their imperial listener’s credulity.”

“Clown and natural peoples: negation of inner impulses and the body’s core. A new integration of clothing, tattoo and body…Following this logic, the discovery of a potential for profound expressiveness: the man sitting in a chair remains seated after the chair is pulled away.”

—Walter Benjamin, Fragment on Negative Expressionism

Walter Benjamin’s fragment on negative expressionism, filtered through Devin Fore’s book from last year, Realism After Modernism, left a mark on me this week. And that would be the right way to put it, after all, since the idea of negative expressionism suggests not the subjective vantage point of Expressionism but its inverse: the thoughts and emotions of material history marking the body. This is second nature to us now. Think about how we don’t think about tattoos.

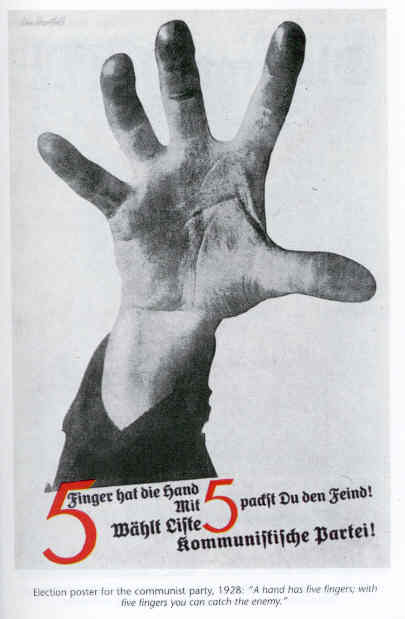

Fore’s book stops short of establishing a dialectic between disintegration (the subject overwhelmed by material history) and the realist reconstitution of the human figure. Instead, Fore demonstrates—through the work of Moholy-Nagy, Brecht, Jünger, and, my personal favorite, John Heartfield—how interwar realism was undergirded by the de-centering of human perception achieved by the avant-garde. The above artists and writers were aware that realism was already infected by vanguardism, and that’s what set them apart.

While reading Benjamin’s fragment, and Fore’s book, I was struck by a series of questions: How aware is the contemporary novel of its repressed vanguardism? How truly confident is the contemporary novel in the robust, upright human figure gliding through history? Is the American reader ready for a return of the repressed, of novels where history moves through its characters, sometimes obliterating them?

—J. Kyle Sturgeon