The Nigerian National Identity Management Commission (NIMC) and MasterCard today announced at the World Economic Forum on Africa the roll-out of 13 million MasterCard-branded National Identity Smart Cards with electronic payment capability as a pilot program. The National Identity Smart Card is the Card Scheme under the recently deployed National Identity Management System (NIMS). This program is the largest roll-out of a formal electronic payment solution in the country and the broadest financial inclusion initiative of its kind on the African continent.

As part of the program, in its first phase, Nigerians 16 years and older, and all residents in the country for more than two years, will get the new multipurpose identity card which has 13 applications including MasterCard’s prepaid payment technology that will provide cardholders with the safety, convenience and reliability of electronic payments. This will have a significant and positive impact on the lives of these Nigerians who have not previously had access to financial services. […]

The new National Identity Smart Card will incorporate the unique National Identification Numbers (NIN) of duly registered persons in the country. The enrollment process involves the recording of an individual’s demographic data and biometric data (capture of 10 fingerprints, facial picture and digital signature) that are used to authenticate the cardholder and eliminate fraud and embezzlement. The resultant National Identity Database will provide the platform for several other value propositions of the NIMC including identity authentication and verification.

Thanks to the unique and unambiguous identification of individuals under the NIMS, other identification card schemes like the Driver’s License, Voters Registration, Health Insurance, Tax, SIM and the National Pension Commission (PENCOM) will benefit and can all be integrated, using the NIN, into the multi-function Card Scheme of the NIMS. When fully utilizing the card as a prepaid payment tool, the cardholder can deposit funds on the card, receive social benefits, pay for goods and services at any of the 35 million MasterCard acceptance locations globally, withdraw cash from all ATMs that accept MasterCard, or engage in many other financial transactions that are facilitated by electronic payments. All in a secure and convenient environment enabled by the EMV Chip and Pin standard.

So, Nigeria is becoming a cashless society. The above paragraphs are drawn from a press release issued by MasterCard earlier this month, and honestly the whole thing is worth a careful read. I don’t usually splash about in these particular waters, so the spittle-gush of financial-cum-humanitarian newspeak caught me totally off guard: philanthropists and technocrats sweat to implement beneficent “financial inclusion initiatives,” which include “bringing bank access” to “unbanked” areas of the world (did you know that 80% of sub-Saharan Africa is “unbanked”?), while also innovating new “identity technologies” that allow more people to “assert their identities.” (That last phrase is downright philosophical, isn’t it?)

The offered rationale for the plan is a Gordian knot of stupid, and is worth lingering on for a minute. As the CEO of Access Bank (a major, publicly traded, internationally entangled Nigerian bank) puts it: “The new identity card will revolutionize the Nigerian economic landscape, breaking down one of the most significant barriers to financial inclusion—proof of identity, while simultaneously providing Nigerians with a world class payment solution.”

It’s true that, in a lot of cases, lack of a valid ID can lead to one’s being “financially excluded”—from holding a bank account, say, or having a credit card. In fact, the only form of “economic participation” that doesn’t require a valid ID is—yep—cash. This plan will actually severely decrease “financial inclusion,” because all those without these comically dystopian credit-card IDs—or all those who don’t want them—will have no way of participating in the economy.

Needless to say, the potential for government (or corporate! or foreign government!) abuse here is potentially limitless. As Timothy Alexander Guzman put it in a good article on the rollout of this plan: “The problem with a cashless society is that the state can terminate your electronic financial lifeline if anything were to happen within the country, for example any form of protests, economic downturns, a war or if a financial institution such as MasterCard were to go bankrupt.”

—Jac Mullen

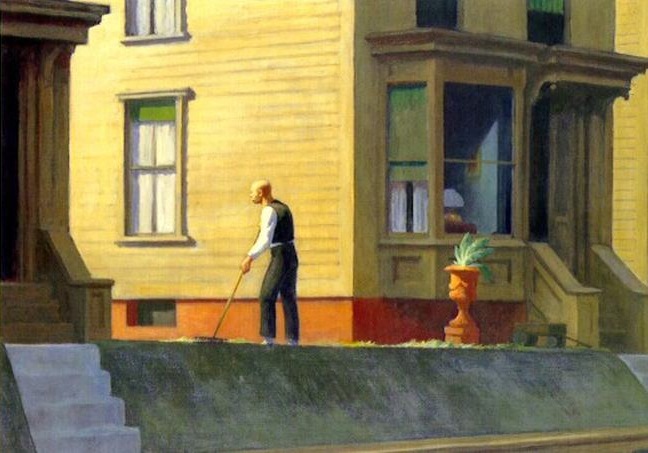

The moment of his looking up seems more than one of distraction. It has the feel of transcendence, as if some revelation were at hand, as if some transforming evidence were encoded in the light. … It is like an annunciation. The air is stricken with purity. And we are involved in a vision whose source is beyond us, and whose effect is difficult to embrace. After all, we view the scene from the shade. And all we can do from where we stand is meditate on the unspoken barriers between us.

In my first week in my first Queens apartment of my first summer in New York, I’ve been seeing Edward Hopper paintings everywhere. In an orange shirt an old woman smokes by a turquoise railing; a girl pauses in a crosswalk with her skirt catching sunlight and air; green weeds shock a vacant lot under a train trestle. All things seem as I pass to grow luminous and solidify, acquiring a kind of indefinable importance—each sight a revelation, but also a revelation of how much I do not yet understand. I see Hopper, I think, because I see as a newcomer, fascinated by the ordinary as if, or because, it is part of a separate world.

Such themes of uncertainty and alienation are prominent in the poet Mark Strand’s 2011 book Hopper. Here, painting by painting, Strand deconstructs the formal elements of Hopper’s work to reveal what could be read as a philosophy of privacy, analyzing what is revealed and what is left mysterious between the subjects and viewers of the paintings. Stylistically the criticism, much like the paintings, restrains itself; simple sentences and concise comments come together like the flat planes of color that structure Hopper’s enigmatic world. While acknowledging the narrative quality of the images he writes about, Strand resists the temptation to speculate on stories, commenting mainly on concrete details of the paintings (such as the position of the figures or the lines leading the eye) to give his own observations the solidity and depth that Hopper achieves through his treatment of shadow and light.

When he does venture into narration, however, as in the above passage on Pennsylvania Coal Town (1947), Strand’s commentary is at its most compelling and most haunting—not because he has finally chosen to give an explanation for what happens in the painting, but because he has made clear the impossibility of explaining it. What I love about Hopper is that it illuminates obscurity, not in the sense of clearing up the mystery, but of celebrating the mystery itself.

—Rosa Inocencio Smith

The by turns fascinating and frustrating debate surrounding International Art English (IAE) began last year with a Triple Canopy piece by Alix Rule and David Levine. In the piece, titled “International Art English,” Rule and Levine ram a bunch of art world texts—namely, art world institutional announcements from the organization e-flux—into a word-policing “engine” and pretend that the yield is something like critical thought. Namely, Rule and Levine believe that they have identified IAE, a kind of variant on standard English, as the lingua franca of the art world.

I have major issues with the original piece, especially the way it reproduces the police logic of big data and sociology, but thankfully, both Triple Canopy and e-flux have kept the debate alive with a series of new essays and responses, linked below.

The original essay, “International Art English”:

“IAE, like all languages, has a community of users that it both sorts

and unifies. That community is the art world, by which we mean the

network of people who collaborate professionally to make the objects

and nonobjects that go public as contemporary art: not just artists and

curators, but gallery owners and directors, bloggers, magazine editors

and writers, publicists, collectors, advisers, interns, art-history

professors, and so on.”

Two responses in the new issue of e-flux Journal:

Hito Steyerl’s “International Disco Latin”

“According to Rule and Levine, IAE is, or might be, spoken by an

anonymous art student in Skopje, at the Proyecto de Arte

Contemporáneo Murcia in Spain, by Tania Bruguera, and by interns

at the Chinese Ministry of Culture. At this point I cannot help but ask:

Why should an art student in Skopje—or anyone else for that matter—

conform to the British National Corpus? Why should anyone use

English words with the same frequency and statistical distribution

as the BNC? The only possible reason is that the authors assume that

the BNC is the unspoken measure of what English is supposed to be: it

is standard English, the norm. And this norm is to be staunchly

defended around the world.”

Martha Rosler’s “English and All That”

“In light of the movement toward other forms of quantification, the

relatively simple statistical methods employed by Rule and Levine

look somewhat benign, though no less antihumanist.”

Mariam Ghani responds at Triple Canopy, “The Islands of Evasion: Notes on International Art English”:

“Like the Chinese activists and their coded language, the more

deliberate users of IAE may, in fact, be exploiting its ambiguities to

conceal something, or to conceal some lack, for good reasons or bad.

Or they may simply be flashing their credentials: I know the

passwords, I speak your language, now will you please open the

door?”

—Jonathon Kyle Sturgeon

Having a Coke with You

is even more fun than going to San Sebastian, Irún, Hendaye, Biarritz, Bayonne

or being sick to my stomach on the Travesera de Gracia in Barcelona

partly because in your orange shirt you look like a better happier St. Sebastian

partly because of my love for you, partly because of your love for yoghurt

partly because of the fluorescent orange tulips around the birches

partly because of the secrecy our smiles take on before people and statuary

it is hard to believe when I’m with you that there can be anything as still

as solemn as unpleasantly definitive as statuary when right in front of it

in the warm New York 4 o’clock light we are drifting back and forth

between each other like a tree breathing through its spectacles…

Our upcoming issue features the lovely poem “Candor” by Jacqueline Waters. In her meditation on the uncertainties of relationships new and old, she mentions the Frank O’Hara poem, “Having a Coke with You.” I’m not much one for poetry, but both of these poems struck a nerve.

O’Hara’s poem lists all the things that are not better than “Having a Coke with You”: exotic vacation locales, paintings by the old Masters, “all the portraits in the world” (well, not the Polish Rider at the Frick, but they can go look at it together sometime), Futurism, statuary. It is a poem about the headiness of falling in love, where simply being with a person is better than everything beautiful and important that used to matter. I realize how saccharine it sounds— How do I love thee? / Let me count the ways—but the poem saves itself with a stream-of-consciousness narration that conveys the giddiness of those early electrifying moments in a relationship and with the—dare I say—brave declaration of love:

it seems they were all cheated of some marvelous experience

which is not going to go wasted on me which is why I am telling you about it

—Lauren Leigh