A dark, alarming Futurism lurks behind the logic of drone strikes, big data, and the Austerity Sequester, one that eliminates minority dissent in favor of the predictive and precisive tools of technocracy. Soon enough (I hope) we’ll see contemporary fiction’s response to this turn of events; in the meantime, we have the films and commentaries of Thom Andersen. It’s not so much that Andersen takes any of these issues head on, but rather that he gives voice to what he calls a “militant nostalgia.” In Los Angeles Plays Itself, his masterpiece and “city symphony in reverse,” Andersen manages to redescribe Los Angeles, the most photographed city in the world, via an amazing parataxis of word and image, giving it back a history that has been systematically destroyed by technocratic Hollywood.

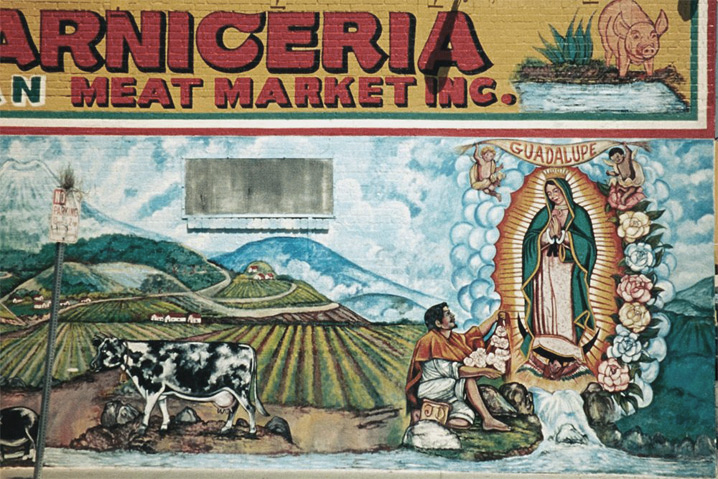

In Get Out of the Car, Andersen composes a different kind of city symphony through the material history of the city’s billboards and murals; in the process, he courts conservatism but ultimately rejects it. It turns out when you’re battling the destructive capacities of an accelerating Futurism, you have two options: either defend the past for what it was or change it into what it should have been. Andersen explains “militant nostalgia” below:

“Get Out of the Car could be characterized as a nostalgic film. It is a

celebration of artisanal culture and termite art (in Manny Farber’s

sense, but more precisely in the sense Dave Marsh gives the phrase in

his book Louie Louie). But I would claim it’s not a useless and reactionary

feeling of nostalgia, but rather a militant nostalgia. Change the past, it

needs it. Remember the words of Walter Benjamin I quote in the film:

even the dead will not be safe. Restore what can be restored, like the Watts

Towers. Rebuild what must be rebuilt. Re-abolish capital punishment.

Remember the injustices done to Chinese, Japanese, blacks, gays, Mexicans,

Chicanos, and make it right. Put Richard Berry, Maxwell Davis, Hunter

Hancock, Art Laboe, and Big Jay McNeely in the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame.

Bring back South Central Farm. Only when these struggles are fought and

won can we begin tocreate the future.”

—J. Kyle Sturgeon

“Surrounded by all these demented individuals, [Hakim] alone maintained command of his rational powers as he stood there silently, absorbed in his own world of memories. Perhaps it was the austerity of his demeanor, but strangely enough the lunatics seemed to stand in awe of him. Not a single one of them dared lift his eyes to gaze upon him, and yet something impelled them to gather around him—like plants in the final hours of the night, already turning towards the light that is still nowhere in sight…”

—“The Tale of the Caliph Hakim,” from Gerard

de Nerval’s The Women of Cairo

Gerard de Nerval is known best, if he is known at all, for his pet lobster Thibault, whom he would lead by a blue satin leash on long evening strolls through the gardens of the Palais-Royal. As an author, Nerval is treated not so much as a point but a vector, someone whose chief import derives from the work he inspired rather than the work he produced. In Ezra Pound’s (slightly dubious) taxonomy of writer-types, Nerval would likely be sorted somewhere between an “inventor” and “starter of crazes”: reliably cited as a forerunner of—and catalyst for—French Symbolism (Proust called Nerval’s Sylvie “a masterpiece”) and Surrealism. Today, Nerval’s work is read far, far less than the work of those he influenced.

—And this is a huge shame, because it’s head-and-shoulders better than nearly anything that came out of, e.g., Breton’s (campy, hieratic) workshop, and also ensures—due to the supposed disinterest of the reading public—that vast swathes of his work remain un-translated, and so unavailable to English readers.

The above passage is drawn from Voyage en Orient, Nerval’s playful, labyrinthine, parafictional account of his travels in Egypt. The only unabridged translation of the work (titled, inexplicably, The Women of Cairo) is long out of print, although a paperback version from one of those awful, out-of-mom’s-garage publishing houses that peddle public domain works for considerable profit, can be purchased here. However, the passage—as well as the rest of “The Tale of the Caliph Hakim”—can be found in the Penguin Classics’ anthology of Nerval’s work, Selected Writings. As a recounting of the life of Abu Ali Mansur Tāriqu l-Ḥākim, the central figure of Druze theology, “Caliph Hakim” is an ideal introduction to Nerval, to his stylistic tendencies (mock-academic or journalistic patios; parafictive “personal” narrative) and thematic preoccupations (altered states of consciousness; the ‘Orient,’ as refracted through Western esoteric traditions; manuscripts, archives, codices).

One last point, which I’ll leave a bit gnomic: in rereading “Caliph Hakim” last week, I became nearly convinced that this very story gave Borges the idea for “Herbert Quain”—specifically, Quain’s last book of stories: “Each of [these stories] prefigures, or promises, a good plot,” explains Borges’ narrator, “which is then intentionally frustrated by the author. One of the stories (not the best) hints at two plots; the reader, blinded by vanity, believes that he himself has come up with them.”

In fact, for someone who is so often treated as merely ‘important,’ it’s terrifically strange that Nerval’s most obvious and significant—or, better, significative—literary-son, Borges, is rarely (if ever) mentioned in relation to him. And yet, the above tally of stylistic and thematic tendencies also describes, as it does no one else, Borges.

Okay. Is all. Read Nerval.

—Jac Mullen

“But the future sometimes dwells in us without knowing it, and the words thought to be untruthful describe an imminent reality.”

—”What are you reading lately?”

—”Proust?”

This has been my general answer to that question for the past several years, often mumbled embarrassedly for fear of seeming pretentious. However, a friend recently made the observation that if I were to read one book for the rest of my life, In Search of Lost Time would be a good pick, maybe the best. Perhaps no other novel so accurately describes the exhilarating and banal, the dizzying and the plebian as well as In Search of Lost Time. The entirety of human experience depicted––and it’s funny, too.

The quote from Sodom and Gomorrah, the fourth volume of Proust’s epic novel, touches upon the themes of memory and time for which the book is so famous. What I find so moving is the thought that our lives do not stretch out ahead and behind us linearly, but instead we exist as a sort of palimpsest in which our future desires and past actions, although subconscious and unrealized or as of yet unknown, will unfold and reveal themselves. Our subjective truths and untruths may at some purportedly objective point in the future reveal their true motives and intentions to us.

Since my answer to everything is always Proust, I should also recommend the centennial celebration of Swann’s Way at the Morgan Library & Museum to our New York readers. “Marcel Proust and Swann’s Way: 100th Anniversary” is a collection of letters, notebooks, and other documents relating to Proust and the publication of his masterpiece. Running until April 28, 2013 and with the first day of spring soon upon us, I can’t think of a better way to spend a spring Sunday.

—Lauren Leigh