I found myself in Vegas earlier this month, and in the wee hours of my last morning there, I laid myself out on a carpet made to look like grass. I had crashed R. and D.’s hotel room, and D. was now introducing me to the music of Joey Bada$$ and Pro Era. It’s kind of shameful that I didn’t know their music until then, but in my defense I’ve fled rap music because (like “country music,” which, in the popular imagination, now seems to be a reasonably cute girl singing pop tunes shot through with half-baked twang) the stuff that gets to travel under the name “rap” is generally low-grade pop nonsense, occasionally catchy, featuring anemic wordplay and tinny, shallow audio. The aural, playground-lush of ’90s beats has been more or less abandoned, and the rhymes seem to need…a helping hand. This song, though, and the entire album “1999,” has delivered me back to the grand hip-hop of my youth: that music that could set the scene, set the mood, invite contemplation, provoke action. It is innocence, it is wisdom, it is youth in revolt—a welcome soundtrack for summer or any time, especially now, as our government gets increasingly punch-drunk on itself and its excesses. It’s also a nice response to the public shanking the other youth-in-revolt music movement—punk—got at the Met Ball earlier this season.

—Uzoamaka Maduka

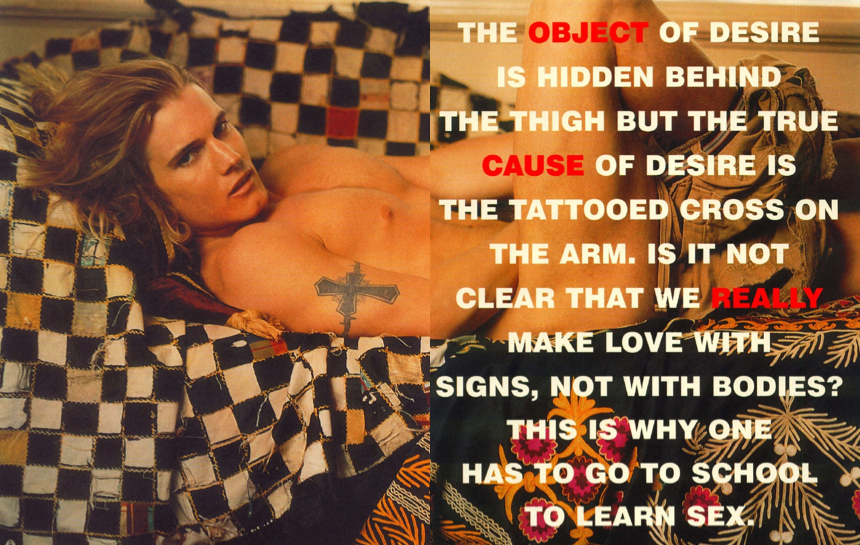

By now, the world is used to Slavoj Zizek’s bloated, frenetic, rollercoaster genius. But in 2003, right off the publication of an esoteric book attacking the consequences of the “radical chic” of Deleuzian philosophy in a digital age (one wonders now if the same radical chic has not turned on Zizek himself), Zizek decided to shock the worldwide academic philosophy community (an easier task couldn’t be imagined) and write advertisement copy for a slightly pornographic Abercrombie & Fitch catalogue.

The full catalogue has recently resurfaced on the Internet in a downloadable (although somewhat cumbersome at 100+ pages) PDF format, and now, ten years on, a certain harmony seems to be emerging between Zizek’s typography and the resplendent and nubile backsides of the A&F models. Now that Zizek no longer has to defend himself against over-intellectualized accusations of being a “sellout” by writing copy for a clothing company, we can see the work for what it actually is: amazing text art.

Who wouldn’t want a wall-sized matte print of this text, masking bushing, partially nude cowboy twins?

there can be no friendship between twins: they

are too close, so the only way for each of them to

maintain his identity is to liquidate the other. a

friend has to be outside my reach, beyond my grasp.

and there can be no friendship with someone whom

i am not ready to betray: a friend is someone i can

betray with love.

In my strangest dreams I imagine this catalogue beginning a new trend in analytic philosophy or critical theory, or at least several interesting tumblr accounts. (I fantasize of John Searle’s prose in a smart typeface over the alabastrine curvatures of Marc Jacobs lingerie models.)

We all know that sex can sell anything, even philosophy, but here, Zizek asks the question: Can philosophy sell sex?

—J. D. Mersault

“There are only two mopeds still parked on the sidewalk in front of the cafe now: I didn’t see the third one leave it was a velosolex) (Obvious limits to such an undertaking: even when my only goal is just to observe, I don’t see what takes place a few meters from me: I don’t notice for example, that cars are parking)

A man passes by: he is pulling a handcart, red.

A 70 passes by.”

—Georges Perec, An Attempt At Exhausting A Place In Paris

“An idealised scene. Space as reassurance.”

—Georges Perec, The Page

Having just moved to New York from Alabama, I can say with certainty that these quotes carry a heavy, edifying weight for me. I have always had a fondness for being “caged in.” By that, I mean the idea of being bound to my limitations, of being forced to revel in the distances between my subjective ideals and the phenomena that wash over me, has always held appeal.

Perec writes confidently about the depth of, and our participation with, space, speaking confidently to the principles of Euclidean space-time relations. Perec even catches himself (in the above quote), calling himself out on his limitedness: knowledge of his own teleology.

New York is fast. Nothing that I did not see coming, especially after experiencing Perec’s strikingly factual prose. But of course, that does not assuage the rush of contextual, significant properties that come along with living in a city as large as this one. Am I frightened by this shift? No. This is merely observational, participatory.

—DeForrest Brown

Trapped in gridlocked traffic from New York to Boston, in the middle of a torrential downpour, I had the opportunity—the time, rather—to become thoroughly reacquainted with one of my favorite jazz albums, Keith Jarrett’s Köln Concert. The album still has a disarming Proustian effect on me, sending me back to a particular dorm room, with a particular person, during the spring of my sophomore year of college.

Maybe it was the way the crescendos and decrescendos mimicked the rhythm of the rain falling on the car window, or my exhaustion after having listened to the first hour of the concert without having moved more than ten miles, or simply my finally being shaken from my nostalgic stupor, but I became completely unhinged by the last five minutes of Part II b (Track 3) of the concert.

Somewhere around minute twelve, Jarrett begins vamping over the theme that will become the through-line to the section. The ritard around 13:10 is stunning, and the light flourishes until the complete shift in dynamic from forte to piano through minutes thirteen to fourteen made me gasp out loud. There’s something so soothing about the vamp and the steady repetition of only a few chords in minute fourteen, leading up to the scales and final trills of this section, in which we hear occasional echoes of the piece’s earlier intensity emerging before the final fade out, before the pristine calm following the storm.

—Elianna Kan