Somehow, beyond noting that “In many ways, Mr. Rhodes is an improbable choice for a job at the heart of the national security apparatus,” the Times is not sufficiently curious about any of this to probe further. Instead, it provides a clutch of clichés. We learn that the Rhodes family is fiercely divided between Yankees fans and Mets fans. We learn the father is a conservative-leaning Episcopalian from Texas, the mother a liberal Jew from New York.

Though the Times never underlines this, the careful reader comes to realize that Rhodes’s guiding philosophy is as hard to discern as the precise reasons that he has the president’s ear. In 1997, he briefly worked on the re-election campaign of New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, a Republican. Shortly after 9/11, the aspiring novelist suddenly decided to do his part for society, moving in 2002 from Queens to Washington, and quickly found himself “helping draft the 9/11 Commission report as well as the Iraq Study Group report.”

The Times, of course, does not think it is worth pointing out how strange this is. It is almost as if all 24-year-olds with no apparent credentials of any kind go directly to explaining the most massively controversial and complex set of circumstances to the American people. […]

The above is taken from Russ Baker’s semi-recent article (it was published roughly a month ago) on the New York Times’ properly beguiling profile of Obama’s deputy national security advisor and speechwriter, Benjamin Rhodes. I call it “beguiling” because, as Mr. Baker’s article plainly illustrates, it contains no actual thinking at all. How the article’s author, Mark Landler (who, horrifically, is the Times’ White House correspondent), could devote full paragraphs to the folksy idyll of the Rhodes family home and give only half a sentence to the fact that, e.g., Rhodes’ brother is the president of CBS News (“‘No one in that house agreed on anything,’ said David Rhodes, who is now president of CBS News”), simply beggars belief. The article is so stupid as to make its publication dishonest.

I bring this up now for two reasons. First, to draw more attention to the work of Mr. Baker, who is surely one of the very best “investigative” (read: actual) journalists working today. His website, whowhatwhy.com, features some great demonstrations of actual journalistic thinking, while his 600-page book on the Bushes, Family of Secrets, is extremely important (I just realized I’m parroting Gore Vidal here: he called it “one of the most important books of the past ten years”), and contributes a lot to helping one make sense of where the country is and where the country’s heading.

Because—and this is the second reason—we do need to make sense of it, because we have a news media that writes pieces like the profile of Rhodes. We have a news media that, principally, has no instincts and asks no relevant questions—and is failing, spectacularly, to write the first draft of history.

—Jac Mullen

“My blood was in a ferment within me, my heart was full of longing, sweetly and foolishly; I was all expectancy and wonder; I was tremulous and waiting; my fancy fluttered and circled about the same images like martins around a bell-tower at dawn; I dreamed and was sad and sometimes cried. But through the tears and the melancholy, inspired by the music of the verse or the beauty of the evening, there always rose upward, like the grasses of early spring, shoots of happy feeling, young and surging life.”

—Ivan Turgenev, Translated by Isaiah Berlin

This passage from the beginning of Ivan Turgenev’s First Love demonstrates the manner in which the novel treats its narrator Vladimir’s youth. Vladimir describes his innocent, lustful idealism with a nostalgia that avoids condescension, instead celebrating its transient power and beauty. He begins and ends this passage with the latent violence of “ferment” and “surging,” framing the delicacy of his “flutter[ing]” and everything he “dreamed” within powerful motion.

He grounds this motion in its own repetition, as it “circle[s] about the same images,” and in the inevitability of nature, of “martins” and of “spring”; there is cyclical meaning in its fragile impermanence. As the cherry blossoms finally burst open, Turgenev’s effusive, thoughtful appreciation for the power of ephemeral beauty feels relevant and comfortingly right. My Russian lit teacher told me that First Love should only be read before eighteen or after thirty; I think it should be read in the spring. Turgenev is so simultaneously thoughtful and engaging that a close reader of any age can appreciate his portrait of youth, idealism, and obsession; but, as in this passage, these things are closely associated with all the rising “upward” of spring. Take First Love to Central Park and read it lying in the grass, before the season turns.

—Nora Battelle

“Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.”

Marcel Proust’s famous opening line (translated by Lydia Davis as “For a long time, I went to bed early”) is a seemingly simple sentence for a writer famous for his verbosity. However, as I discovered in the exhibit “Marcel Proust and Swann’s Way: 100th Anniversary” at the Morgan Library, Proust waffled on his final choice until very late in the publishing process. Scribbled in the margins of the typescript of Swann’s Way, he composed a different first sentence:

“At the time of that morning, whose memory I would like to fix, I was already ill; I would be up all night and went to bed only during the day. However, the time when I would go to bed early and, with a few short interruptions, would sleep until morning, was not that far in the past, and I was still hoping that it could return.”

This alternate sentence reveals more explicitly Proust’s focus on temporality and memory. I would, however, argue that in its very simplicity, Proust achieves far more with his final choice of opening line; playing with literary convention and temporality, he deftly achieves a layered complexity in eight words. Written in passé composé instead of the literary passé simple tense, Proust chose a verb tense that is generally reserved for spoken conversation. Additionally, although the imperfect tense would normally have been used for the repeated action of going to bed, his use of “longtemps” allows him to choose the passé composé instead. This opener already plays with time, extending and dilating an event that, according to its verb tense, would only occur once, and setting the stage for themes that reappear continuously throughout In Search of Lost Time.

The Proust exhibit is a fun and revealing look at the author’s writing and editing process—and it’s only open for another week. For those Readers not in New York, the Bibliothèque nationale de France has created an accompanying audio slideshow of some hand-corrected galley sheets of Swann’s Way.

—Lauren Leigh

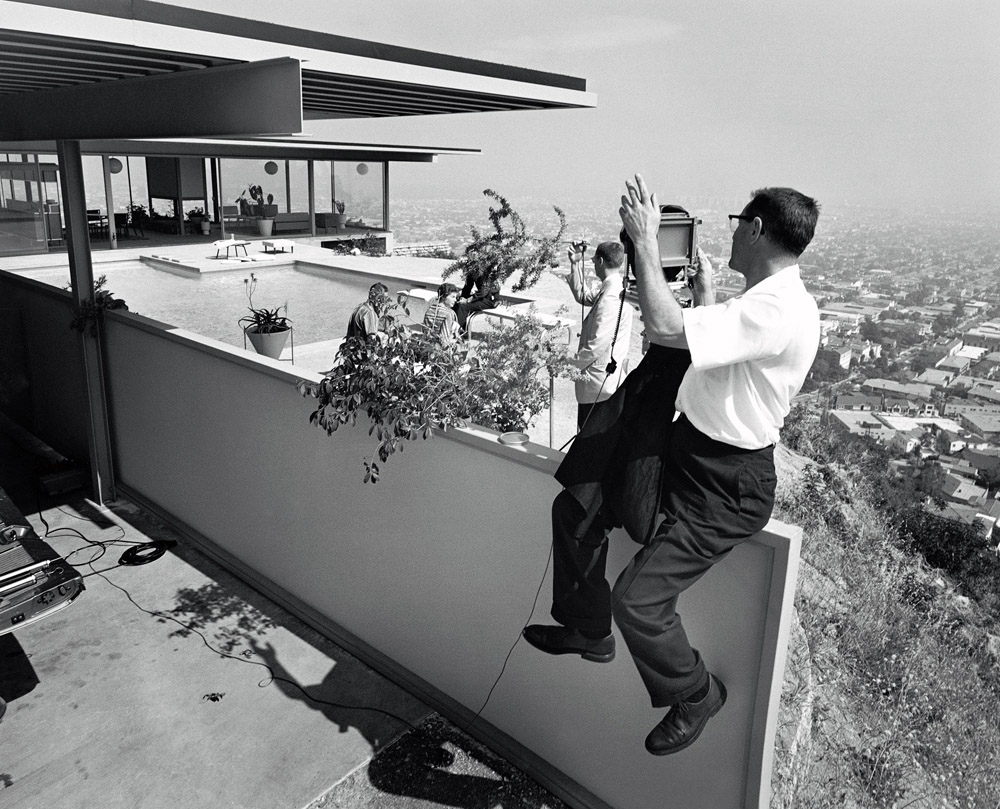

The other day I stumbled across this rare photo of Julius Shulman setting up to take one of his many acclaimed photos of a piece of modern, prefab architecture in Los Angeles. This photo strikes me more than Shulman’s actual work for several reasons. Shulman appears to be at such a distance from the house, yet his chord disappears into the shadows of this almost sublime structure towering over the California landscape. There is a dual tension created by the house perched on the cliff, and the photographer perched on the house. The photo seems to have three different conflicts going on: between man, the fabricated, and nature, and it is impossible to tell what is dominant. It enforces an air of precariousness in the picture, that I think accurately portrays the tension of the Cold War era.

The other day I stumbled across this rare photo of Julius Shulman setting up to take one of his many acclaimed photos of a piece of modern, prefab architecture in Los Angeles. This photo strikes me more than Shulman’s actual work for several reasons. Shulman appears to be at such a distance from the house, yet his chord disappears into the shadows of this almost sublime structure towering over the California landscape. There is a dual tension created by the house perched on the cliff, and the photographer perched on the house. The photo seems to have three different conflicts going on: between man, the fabricated, and nature, and it is impossible to tell what is dominant. It enforces an air of precariousness in the picture, that I think accurately portrays the tension of the Cold War era.

—Sarah Goldfarb

VIDEO: Poetry (No Venue Necessary)

Though I have mixed feelings about spoken word poetry—the bad imitations are really bad—I love what this group, Poets in Unexpected Places, is trying to do. If I can be held captive by a tone-deaf teenager who thinks he’s Usher, why not also hear a little poetry on the morning commute? I love this idea of taking poetry down from its seemingly lofty tower and placing it in the most banal and unexpected of settings.

—Elianna Kan