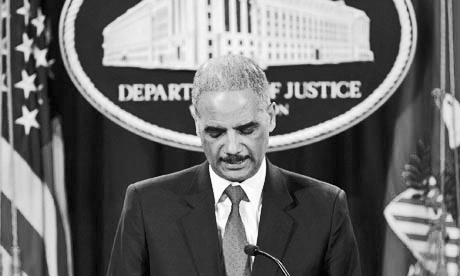

US attorney general Eric Holder defends AP seizure

US attorney general Eric Holder defends AP seizure

“What makes the DOJ’s actions so stunning here is its breadth. It’s the opposite of a narrowly tailored and limited scope. It’s a massive, sweeping, boundless invasion which enables the US government to learn the identity of every person whom multiple AP journalists and editors have called for a two-month period. Some of the AP journalists involved in the Yemen/CIA story and whose phone records were presumably obtained – including Adam Goldman and Matt Apuzzo – are among the nation’s best and most serious investigative journalists; those two won the Pulitzer Prize last year for their superb work exposing the NYPD’s surveillance program aimed at American Muslim communities. For the DOJ to obtain all of their phone records and those of their editors for a period of two months is just staggering. It’s the very opposite of what the DOJ has long claimed its guidelines protect. EFF details how the DOJ’s actions “violated its own regulations for subpoenas to the news media.”

The key point is that all of this takes place in the ongoing War on Whistleblowers waged by the Obama administration. If you talk to any real investigative journalist, they will tell you that an unprecedented climate of fear has emerged in which their sources are petrified to talk to them. That the Obama administration has prosecuted double the number of whistleblowers under espionage statutes as all previous administrations combined has already severely chilled the news gathering process. Imagine what message this latest behavior sends to journalists and their sources: that at any moment, the phone records of even the nation’s most establishment journalists can be secretly obtained by the DOJ, which has no compunction about doing so even in the most extreme and invasive manner.”

The above comes from a new article by Glenn Greenwald, published yesterday morning on The Guardian’s website. Greenwald is discussing Monday’s revelation that the Department of Justice had legally and transparently obtained two months of telephone records of terrorists who worked for the Associated Press.

Oh, wait—sorry: the Department of Justice had secretly obtained two months of telephone records of journalists and editors who worked for the Associated Press. According to the AP itself (which, fittingly, broke the story): “In all, the government seized the records for more than 20 separate telephone lines assigned to AP and its journalists in April and May of 2012. The exact number of journalists who used the phone lines during that period is unknown, but more than 100 journalists work in the offices where phone records were targeted, on a wide array of stories about government and other matters.”

Three things, (as) quickly (as possible): first off, Glenn Greenwald is a fantastic journalist. Since the Bush years (when he blogged over at Salon—he now has a kind-of-daily column at the Guardian), he has been among the most dogged and committed chroniclers of the protracted, preventable, ongoing, and utterly tragic erosion of our basic civil liberties in the name of homeland “security”—begun under Bush and continued, effortlessly, brazenly, without missing a beat, by the Obama DOJ and CIA. Greenwald’s a swift, careful, punishingly logical thinker, and it’s a considerable pleasure—if not a minor revelation in its own right—to watch his rare appearances on cable news.

Secondly, he’s often the only comfortably “mainstream” journalist to pen stories on instances of collusion between journalists and governments or corporate interests. For some good recent ones, check out here his piece on a ‘secret’ email correspondence between NY Times editor Mark Mazzetti and a CIA spokeswoman, discussing a potentially negative portrayal of the agency in a forthcoming Maureen Dowd editorial (“Going to see a version before it gets filed,” Mazzetti assures the spokeswoman. “[T]his didn’t come from me…please delete after you read”). Or, you could also go here, for a piece on CNN-journalist-turned-whistleblower Amber Lyon, and how CNN was straight-up whoring itself out to repressive regimes in foreign states, taking money to produce advertorials (which it presented to its viewers as news) that painted their client’s countries, economies and governments in a flattering light.

Finally, the point Greenwald makes in the second paragraph above—about fear among journalists in the face of the Obama DOJ’s Sherman’s Marching all over whistleblowers (while simultaneously hemorrhaging classified information to, e.g., Hollywood producers)—should give one considerable pause. In fact, Lyon also alleged that CNN editors encouraged its reporters to shy away from material that was overly critical of the Obama administration, for exactly the reasons Greenwald outlines in his article.

—Jac Mullen

“Prose invents—poetry discloses.

A mad man is talking to himself in the room next to mine. He speaks in prose. Presently I shall go to a bar and there one or two poets will speak to me and I to them and we will try to destroy each other or attract each other or even listen to each other and nothing will happen because we will be speaking in prose. I will go home, drunken and dissatisfied, and sleep—and my dreams will be prose. Even the subconscious is not patient enough for poetry.”

I’ve been thoroughly enjoying Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, in which the American poet passionately describes his struggles with language in a series of letters to the Spanish poet Federico García-Lorca. One gets the sense that in spite of his substantial doubt with regard to the power of language to faithfully communicate anything, he desperately yearns for the creation of meaning derived through language. Though overwhelmed by the inadequacies of language, he still wants to create the perfect poem: “I would like to point to the real, disclose it, to make a poem that has no sound in it but the pointing of a finger.” I love the idea that poetry gives Spicer a hope that prose had long ago obliterated.

—Elianna Kan

“Rather than asking for my passport, she simply handed me the register, and I entered my name as Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer, historian, of Landeck, Tyrol.”

I recently recommended (insisted vehemently, actually) that a friend read W. G. Sebald, at once! However, flipping through my own copies, I was reminded of my own struggles reading it—Sebald’s dense, referential, allusive novels need to be annotated.

The above quote is a prime example of this: In Vertigo, Sebald-as-narrator signs seemingly random name in a hotel registry and the plot moves on without comment. However, Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer is hardly an innocuous alias. Fallmerayer was a 19th-century historian who claimed that then-contemporary Greeks were not descended from the “true” ancient Hellenes, but from Slavic migrators; his theories were likely a politically motivated attempt to discredit the legitimacy of the then-emerging Greek nation, and were later used by the Nazis to defend their atrocities during their occupation of Greece during World War II.

I don’t know about you, erudite Reader, but I definitely had to Google that. This is a truly strange moment in the text. Why, in a passing remark, assume the guise of a historian and traveler whose writings were used to justify horrific acts? Shortly, before the narrator assumes the name of Fallmerayer, he is issued a replacement German passport (this, despite having lived in England for decades) and subsequently suffers an intense affliction of the titular disease. Although World War II and its atrocities are only obliquely referred to in Vertigo (and only in Austerlitz does Sebald write about the concentration camps of WWII in a scathing rebuke of the complicity of many Germans in their systematic forgetting of the atrocities committed), I think that Sebald-as-narrator, an exile on his way to a return, is subtly telling the reader that perhaps, he is negotiating his own misgivings about his national heritage and the baggage that comes alongside.

Questions of memory, guilt, nationalism, identity, history, dislocation, and disorientation—all in one seemingly tossed-in detail, easily glossed over. This is one of the reasons I love Sebald, but also returns me to my original point: Publishers, translators, scholars—somebody annotate these novels! I need footnotes, people.

—Lauren Leigh

“The supposedly cuddly quality of cetaceans I just don’t get. Between barnacles and sea lice the few whales I’ve seen up close were hideously, hoarily disfigured or at least blemished and tactiley repellent the way certain so-called—not by me—pizza-faced teenagers are. I’ve seen stray grays in the Sound, come to shore to scratch their backs in Saratoga Passage, and they’ve all had a mottled gray pocked aspect, like poured cement. Their souls may be infinitely sweet and poetic, possessed of an earnestness and bonhomie I can only envy, but their bodies, in terms of color and surface texture, resemble bridge abutments.”

What a thing to say! “Whaling,” which can be found in Charles D’Ambrosio’s 2004 essay collection Orphans, belongs right up there with J.M. Coetzee’s Elisabeth Costello and David Foster Wallace’s “Consider the Lobster” as one of the great recent attempts to write about empathy for animals. The passage makes me a little uncomfortable, though. I’ve always operated under the hazy premise that increased emotional sensitivity (whatever that means) was the unspoken goal of all writing, and that good prose should always broaden, and never limit, the scope of our feelings. It’s unsettling to see a writer as sensitive and as morally discerning as Charles D’Ambrosio deriding whales so casually.

It’s hard to argue with that language, though. D’Ambrosio’s nearly pathological honesty is probably a big part of the reason he hasn’t gotten as much attention as he deserves, and there’s something to be said for periodically questioning the sincerity of the so-called righteous. He goes on to point out that certain activists who preach that “cuddly quality of cetaceans” also promote a naive, racially condescending understanding of the Native American Makah people, whose recent quest for permission to hunt a gray whale has attracted the wrath of animal rights crusaders. “Abstract love is the nosy neighbor of abstract hate,” he writes later on, “they see right into each other’s windows and they always agree on everything.” Maybe, in the interest of keeping it real, there’s some room in literature for the temperance of feelings.

—Russell Jacobs