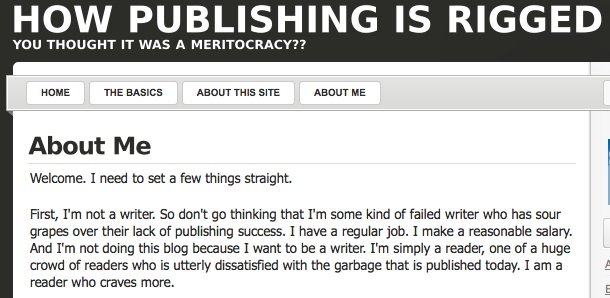

How Publishing is Rigged is a now-defunct blog, penned by a literary industry outsider. Its goal:

“Once you get familiar with what’s available at How Publishing Is Rigged, you’ll witness that publishing is controlled by a handful of individuals and their attendant cliques, and you’ll see that these people are the worst arbiters of quality. …The poor quality of the work has readers abandoning literature in droves. It’s no wonder that the publishing industry is in shambles—nobody wants to read what’s being published today.”

The blogger is driven by what appears to be a pure motive: to demand integrity from an industry that has lost its way. And so even when I disagree with a specific point he/she makes, I am in constant agreement with the project animating its delivery. This is not to say I find myself disagreeing very often; on the contrary, I am routinely impressed and surprised by this blogger’s ability to so clearly, and times even brilliantly, read the industry and its artifacts from his/her remove. If only it were still being updated, I might be able to look forward to HPR’s withering and potentially enlightening take on the Reader’s endeavor…

—Uzoamaka Maduka

“123. Whenever I speak of faith, I am not speaking of faith in God. Likewise, when I speak of doubt, I am not talking about doubting God’s existence, or the truth of any gospel. Such terms have never meant very much to me. To contemplate them reminds me of playing Pin the Tail on the Donkey: you get spun around until you wander off, disoriented and blindfolded, walking gingerly with a hand stretched out in front of you, until you either run into a wall (laughter), or a friend gently pushes you back toward the game.

…

125. Of course, you could also just take off the blindfold and say, I think this game is stupid, and I’m not playing it anymore. And it must also be admitted that hitting the wall or wandering off in the wrong direction or tearing off the blindfold is as much a part of the game as is pinning the tail on the donkey.”

I’ve been losing myself in Maggie Nelson’s little aphoristic book Bluets, her homage to her love affair with the color blue. It takes me to strange corners of my mind, but this last passage really stayed with me. More specifically, I was struck by the power in the simple gesture of removing the blindfold, choosing not to play the game and yet simultaneously acknowledging that even that gesture is merely an illusion, seemingly self-empowering and yet a part of the game all the same….

—Elianna Kan

The insomniac and physically ill Count Kaiserling visited Bach with his personal musician, Goldberg, whose job it was to play in the antechamber of the Count’s bedroom when he couldn’t sleep. The Count asked for music “of such a smooth and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights.” Pianist Glenn Gould, the widely acknowledged master of Bach’s exquisite variations, was also plagued by depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and a hypochondria that would eventually justify itself when he suffered a stroke paralyzing the left side of his body. I’ve always accepted that the heavy-hearted way Gould played was true to the piece, that Bach had ignored the Count’s request for soothing music, not bothering himself too much with the Count’s the instructions. Gould’s rendition is an anatomy of insomnia: the anxiously beating heart, shallow breaths, and the improbably prolonged stillness that an unhappy mind can inflict on the body. The livelier sections are trips to the living room, to the freezer, the fruitless search for a distracting book, any distraction, any diversion.

It wasn’t until I heard the variations played by John Kamitsuka that I felt that Bach might have actually done Count Kaiserling a kindness and humored his patron—that there is a subtle infusion of hopefulness in the piece. Kamitsuka plays for the morning, with a faith that there will be a morning, that you will be restored and distracted again by the day, by other people who are also awake, and that a deep and unwelcome wakefulness is, like all plagues—and also like all blessings—only a visitation.

—Alma Vescovi

“To Julia de Burgos”

“Already the people murmur that I am your enemy

because they say that in verse I give the world your me.

They lie, Julia de Burgos. They lie, Julia de Burgos.

Who rises in my verses is not your voice. It is my voice

because you are the dressing and the essence is me;

and the most profound abyss is spread between us…”

These are the opening stanzas of “To Julia de Burgos” by Puerto Rican writer Julia de Burgos (1914-1953). In 1997, a poet named Jack Agüeros translated the entirety of her works into English, and it was this translation that made its way to me almost a year ago. She came to mind earlier this week, when I was walking over to the Reader’s offices in Washington Heights—at the age of 39, she collapsed and died on a street not far from here, and her unidentified body was buried in a common plot in New York’s Potter’s Field.

The poem is hard to parse, and not merely because “Julia de Burgos” was her pen name only (she was born Julia Constanza Burgos García). A line towards the poem’s conclusion has been with me all morning: “You in you have everything and you owe it to everyone, / while me, my nothing I owe to nobody.”

—Alyssa Loh