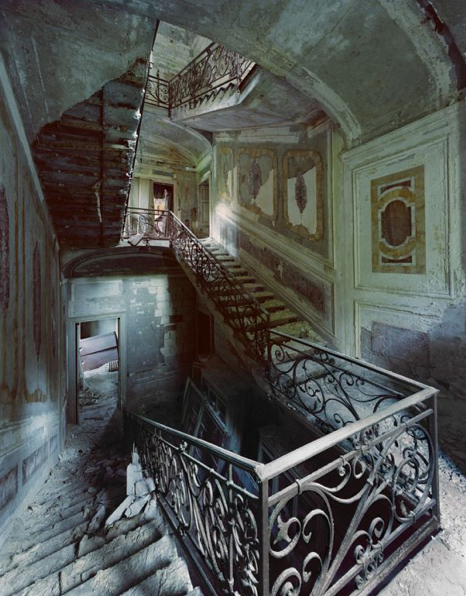

When I stumbled upon Thomas Jorion’s photographs of abandoned palaces (taken while traversing the Northern Italian countryside), I could not shake the images of decaying palaces and villas. Their crumbling vicissitudes were beautiful and poignant in their decline, but mostly they conjured up the spare, quiet lyricism of the setting for Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient.

“From outside, the place seemed devastated. An outdoor staircase disappeared in midair, its railing hanging off. The life was foraging and tentative safety. […] They were protected by the simple fact that the villa seemed a ruin. But she felt safe here, half adult and half child. […] Within the villa she would step from rubble to a candlelit alcove where there was her neatly packed suitcase, which held little besides some letters, a few rolled-up clothes, a metal box of medical supplies. She had cleared just small sections of the villa, and all this she could burn down if she wished.”

I’ll admit to never having seen the movie (I’ll take Elaine Benes’s word for it), but Jorion’s photos clearly revealed the The English Patient that had existed in my imagination–the faded, but still beautiful colors; the feeling of holding one’s breath to not disturb the silence that pervades the novel; the loneliness of abandonment. So for my staff pick, take a look at Thomas Jorion’s photography series, Forgotten Palaces, and then read The English Patient, because it is a book that I have picked up time and time again, especially during this time of year when the earth seems to be holding its breath for the first green shoot to appear.

—Lauren Leigh

forsticulate: (v.) to interrupt others’ sentences, erroneously believing you know what they were going to say

blargant: (adj.) disgusting

mugasm: (n.) the feeling of ecstasy prompted by music

I recently went to workshop on language, part of monthly series in Brooklyn called Ways of Being Together, an experiment in making the word ‘seminar’ inspire less dread. This workshop was run by linguist and writer Ross Perlin, who lead us all in a surprisingly merry discussion of what it means to makes noises other people recognize. In addition to having us make up words, Perlin also introduced us to the concept of evidentials. Completely lacking in English outside of the formalized academic bibliography, evidentials is the practice of citing your sources, no matter how casual the conversation. It asks you to be more specific about how you know what you know, allowing and compelling an explanation of the origin of your statements. The Tibetan language gives us’dug’ indicating direct sensory perception, yod sa red, indicating inference, yod kyi red, indicating hearsay and general knowledge, and finally, rod red, indicating a neutral or private source.

A conversation with my friend Julia using these phrases, in spite of the need to constantly refer to the projection of these phrases on the wall, made me feel this was an inspired directive. Believe me when I tell you that this requirement will make you think very carefully about what you want to say, and that I would be far more ashamed to tell a lie in Tibetan, and probably more likely to be caught. If evidentiality is anything, it is considerate, in every sense of the word, both compelling consideration and demonstrating a mindfulness of your conversational partner. I reflected on what I was saying more deeply to give my statement weight and detail, using four phrases that appear to have dealt with the entire epistemological spectrum, from Empericism to Contructivism. When I saw Julia straining her neck looking at the board to make sure I understood that her account was inspired by general knowledge and not inferred, I felt more considered, that she thought my understanding and opinion were valuable enough to warrant a ‘yod kyi red.’

—Alma Vescovi

“To be an actor you have to love to suffer, and I only like to suffer.”

Abby (played by a wonderful Maria Dizzia) says these words early on in Amy Herzog’s play “Belleville,” which is currently running at New York Theater Workshop. Sadly, Abby does little else but suffer over the course of the play. In ninety minutes—about twenty-four hours for the characters—Abby and her husband Zack (played by an equally remarkable Greg Keller) unravel in such a slow, devastating way that I left the theater feeling that the play should have come with an advisory. “Warning: ‘Belleville’ may cause self-loathing and depression” would have been sufficient.

It might be valuable to look at “Belleville” as a sort of analog to Richard Yates’s 1961 novel Revolutionary Road, an equally disquieting work whose main characters, Frank and April Wheeler, suffer from many of the same anxieties that haunt Abby and Zack. Like Abby, April is a failed actress and a depressive alcoholic. Frank and Zack both have their share of emasculating moments. If you put down Revolutionary Road feeling like the Wheelers might have been saved by their planned expatiation to France, however, “Belleville” is here to shit on your parade. In one of the play’s funnier moments, after everything seems to have fallen apart (it hasn’t—yet), Zack tells Abby that they moved because she had expressed a wish to come to Paris. “I meant for a weekend!” she shrieks. The play might be as brilliant as it is terrible, but be advised: you will not enjoy “Belleville” if you don’t, at the very least, “like to suffer.”

—Russell Jacobs

I recently paid a visit to the Neue Galerie, arguably my favorite art museum in New York—the current exhibition of German Expressionism is well worth seeing. Each time I come back to the Neue, I begin my visit in front of Schiele’s Lovers (Man and Woman I). I’d say it’s my favorite painting, if only favorite didn’t seem to have such a positive connotation. This is a disturbing painting, to be sure, but it’s the one that has stayed with me longer than all the others. The curvature of the man’s disproportionately long arms, the woman’s arched back and head, hung down between her arms—in despair? Defeat? Shame? Pleasure? And those menacing eyes! Somehow they seem somewhat inviting to me, like I’ve been tentatively granted permission to partake in the intimacy—at least at my own risk. Depending on my mood, I find myself creating a different narrative for what might have transpired between these two people and I’m always grateful for their constancy. My own bizarre version of the portrait of Dorian Gray…

—Elianna Kan