One fine morning, I awoke to discover that, during the night, I had learned to understand the language of birds. I have listened to them ever since. They say: “Look at me!” or: “Get out of here!” or: “Let’s Fuck!” or: “Help!” or: “Hurrah!” or: “I found a worm!” and that’s all they say. And that, when you boil it down, is all we say.

—Hollis Frampton, A Pentagram for Conjuring the Narrative

(During this thirty-eight–minute interview, Frampton smokes twelve cigarettes. If he is awake for sixteen hours a day and smokes at a similar rate, by the end of the day he’ll have smoked just over three hundred.)

If you didn’t know Hollis Frampton was at once an artist, writer, filmmaker, philosopher, scientist, photographer, and historian, you might mistake him for a drifter. In his early twenties, between developing mathematical algorithms to determine the precise amount of suffering suffered by each person, producing films comprising entirely of single point perspective shots of lemons, and making abstract expressionist paintings, Frampton studied under Ezra Pound during the modern master’s confinement at St. Elizabeth’s. Later in life he attempted a massive meta-historical film about the circumnavigation of the globe, successfully and accurately predicted the widespread use and proliferation of digital imaging technology as a means of global communication, and developed an early programming language for voice synthesizer software. He was, by all accounts, an astounding polymath of a man. And yet I can easily picture him living in a barrel.

But then again, there’s an uncanny kind of intellectual sincerity that looking more or less homeless can provide. Frampton, somewhat predictably, died of lung cancer in 1984.

—J.D. Mersault

Was it a bad mood that brought me to Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against the Grain? Certainly no contemporary critic encouraged me to read the novel, which is as against the grain now as it was in 1884, when it scandalized critics and even scared and tantalized Oscar Wilde. The prologue describes the prehistory that led to the book’s antihero, Des Esseintes, to self-exile in an obsessively (and hilariously) manicured Parisian apartment:

His nerves were on edge, he was ill at ease; disgusted at the

triviality of the ideas exchanged and received, he was growing

to be like the men Nicole speaks of, who are unhappy everywhere;

he was continually being chafed almost beyond endurance by the

patriotic and social exaggerations he read every morning in the

papers, overrating the importance of the triumphs which an all-

powerful public reserves always and under all circumstances for

works equally devoid of ideas and of style.

Already he was dreaming of a refined Thebaïd, a desert hermitage

combined with modern comfort, an ark on dry land and nicely

warmed, whither he could fly for refuge from the incessant deluge

of human folly.

From start to finish, the whole book is imbued with the state of being pissed off or insulted by the intellectual lassitude of the literary establishment. Osip Mandelstam, writing about the novel, was right as usual:

Its primary theme is the clash between the defenseless but refined

external organs of perception and insulted reality. Paris is hell …

Huysmans’s boldness and innovation stem from the fact that he

managed to remain a confirmed hedonist under the worst possible

conditions… The decadents did not like reality, but they did know

reality, and that is what distinguishes them from the romantics.

Insulted Realism. How else to describe Against the Grain? And although certain contemporary writers do seem to proceed from insult—William Gass and Alexander Theroux both come to mind—we still do not have our Against the Grain. Who will be insulted enough?

—Jonathon Kyle Sturgeon

I know it’s sentimental, but I’m pretty emo right now.

By the time this pick goes up, the gates at Max Fish, the legendary Lower East Side bar, will have shuttered at 178 Ludlow for the last time. I realize how weird (and borderline alcoholic) this will sound to many, but my heart is breaking a little bit right now. There has been a lot of talk of Max Fish as the one of the last holdouts of the old creative, artistic, and fast-disappearing Lower East Side (which is true) and how it’s still gritty and a little dangerous (barely, unless you’re really afraid of tripping over skateboards or a complete idiot). Over the past few weeks, I’ve been trying to figure out how to say goodbye. Daniel Savage has a great photo series in honor of this bar’s final night here that captures a lot of what I’ve been trying to articulate to myself. The strangely brightly-lit bar, the Tom Otterness mustachioed rat policeman statue, the best bartenders behind the bar, and amazing people often sitting on the other side: I’ll miss it all dearly.

The owner, the staff, the regulars, new and old—I’m so grateful to know them and count them among my friends. Some of my best friends have been going there for the past twenty-odd years; I haven’t been that lucky. But this place was a home for many, including myself, and when it reopens in Williamsburg this fall, I know it won’t be exactly the same, but I’ll be there.

—Lauren Leigh

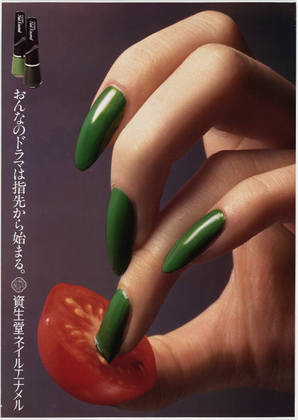

Hand Signals: Digits, Fists, and Talons, on view at MoMA until September 8, features a selection of strikingly beautiful prints and an unsettling sense of impersonality. It’s especially noticeable in an ad for the Engelberg Trübsee resort: a gloved hand in the foreground obscures half a woman’s face, and while the hand surely belongs to her, framing and foreshortening make it seem like a separate entity. In a poster for Luis Buñuel’s film Ensayo de un crimen, a man’s photorealistic hand reaches through the paper to strangle a faintly outlined woman. In a Soviet poster urging voters to “fulfill the plan of great works,” I didn’t at first notice the collage of faces; the hands that surround and envelop them are too overwhelming. Then there’s the reptilian fist of a German ad for war loans, the dangerous beauty of the fingernails in a Japanese nail polish ad. These hands, disembodied and stylized, cease to be human; they might carry a message of empowerment, but their power is so dissociated from the bodies they represent that it threatens to suppress the individual self.

Hand Signals: Digits, Fists, and Talons, on view at MoMA until September 8, features a selection of strikingly beautiful prints and an unsettling sense of impersonality. It’s especially noticeable in an ad for the Engelberg Trübsee resort: a gloved hand in the foreground obscures half a woman’s face, and while the hand surely belongs to her, framing and foreshortening make it seem like a separate entity. In a poster for Luis Buñuel’s film Ensayo de un crimen, a man’s photorealistic hand reaches through the paper to strangle a faintly outlined woman. In a Soviet poster urging voters to “fulfill the plan of great works,” I didn’t at first notice the collage of faces; the hands that surround and envelop them are too overwhelming. Then there’s the reptilian fist of a German ad for war loans, the dangerous beauty of the fingernails in a Japanese nail polish ad. These hands, disembodied and stylized, cease to be human; they might carry a message of empowerment, but their power is so dissociated from the bodies they represent that it threatens to suppress the individual self.

Then again, if faces seem to be an afterthought, it could be because they’re unnecessary. Nietzsche, after all, would say identity lies in action. If so, what’s a hand but identity encapsulated—the shaping grasping feeling enactor of every human impulse worth caring about? I’ll quote Shiseido Nail Enamel: “The drama of a woman begins at the fingertips.” And that’s an even more unsettling thought.

—Rosa Inocencio Smith

“I once told a story about myself and I didn’t recognize myself.”

Thus ends Daniel Kitson’s hilarious and unapologetically honest one-man show, After the Beginning. Before the End, which just had a sold-out one-week run at The Barrow Street Theatre here in New York. This line encapsulates much of what’s at the heart of Kitson’s show, which incorporates elements of a stand-up comedy routine into a tightly scripted philosophical monologue exploring, among other things, the fragile nature of memory, alienation in the digital age, and our desperate reliance on linear narrative for self-affirmation. While these tend to be common thematic tropes of contemporary cultural discourse, Kitson tackles these matters with a rare combination of wry, incisive humor and earnest sentimentality that nearly undercut one another at every turn of his performance. Even as the show seems to come to a comfortable, feel-good conclusion in the form of a number of tightly worded aphorisms, Kitson reminds us, in this last line, of the evasiveness of truth with a capital T, of the inevitable disappointments of narrative, which can never quite capture precisely who we are at any given moment, and thus makes empathy, knowledge of the other, an inherently partial enterprise. And yet we continue telling stories, sometimes in the form of one-man comedy shows…

—Elianna Kan

Lately I’ve been considering the medium in which an artist resides and acts. In Swisher, the new album by Blondes, I was struck pretty immediately by how intelligent this album felt—how it undulates and moves from passage to passage like an ephemeral imagist poem, something akin to Alain Renais’ memory-delving films. The idea of the impressions of motion—within the music and the artist themselves when physically crafting it—is important here. When listening to it, the sun gleaming overhead, people shuffling by, I feel arrested—forced to consider my surroundings. Swisher moves fluidly in a way that reminds me of Erik Satie’s ideas of furniture music, where the repetitive motifs sleekly bore into your sensible environment without giving much notice. In “Bora Bora,” a low and circuitous kick propels the track forward; scraping sounds, cymbals, and rim shots are scattered throughout the mix; and in that moment I feel a tinge of anxiety, or awareness. The album is a thinking thing, thinking about its own form, thinking about me listening. There is a moment in the track “Poland” where the song appears to freeze in place—phasing, reverberating claps being the only marker of time—as the melody ascends and angles, the particulars of it colliding. A high-frequency cacophony emerges. After the entrance of a shaker, the kick slightly shifts the axis and thus the perspective weight of the harmonic development, lurching the track by a third of a beat; out of this, the track unfurls into a newfound warmth. Later, a vocal sample worms its way through, curling inward as it snarls: stasis.

These tracks are sentimentalist pieces, fluidly tectonic, a showcase of scraps from their artists’ various influences. Call it a musical superbug, if you will: By cross-pollination and mutation, Swisher has progressed beyond the structural bindings of its form, and this is what makes it good art. This is true community, dance music for the uninitiated, for those who like to revel in the crystalline and geodetic. Swisher is the experience of musicians thinking about their form and their placement therein, thus producing epistemological house music.

—DeForrest Brown