This essay introduced an excerpt from Jacques Rancière’s Aisthesis in the May/June issue of the American Reader, available here.

✖

By most accounts, the life of the reader has become vita passiva. These days the reader is projected as a sufferer, of markets and technology, of the image and its future. At best willing only to consume, to rifle through trash on her Kindle, ready to relinquish her final moments of quietude to the noise of visual culture, the reader is whispered about as an aphasic oldster awaiting euthanasia. If only she were willing to die, her avatar might be freed to roam the galleries and actually do something relational, participatory, communicative.

The reader is now told more than ever that she is hopelessly inundated by spectacle, that reading itself, like moviegoing, is passiveness masquerading as a pastime. The novel is posed as an antiquated technology. At best, as a form, it never achieved much; at worst it is politically useless. Adventurous writing gives way to the speed of the page-turner or to television. The Wire is like Dickens but faster and more up-to-date. Meanwhile, tenured humanities professors, those élite readers, are mocked and defunded for contributing nothing to the gross national product; in turn, massive online repositories of free books are dismantled in the name of university presses. The wheels of resentment churn; then one of the highest earning literary novelists of the moment declares that the reader is hopelessly torn between markets. The choice, he explains, is between MFA sentimentalists or NYC realists; it is one fist or the other, and soon enough the reader will be sucker punched by literary gentrification.

The reader has been subtracted from Internet culture, too, by those like Lee Siegel who demand that it is a place where everyone writes or posts images, but where no one seriously reads. Or rather, Siegel warns that readers of blogs and web articles will metamorphose into the “mob” that true intellectual culture seeks to destroy. IRL, in NYC, the mob of do-nothing readers is not even allowed to gather. I’m thinking now of those who browsed and borrowed from the 5,000 volumes of free and donated books comprising the bulk of The People’s Library at Zuccotti Park, which was ransacked and destroyed by the New York Police Department on November 15, 2011; or Anthony Marx’s Central Library Plan for the NYPL, which ensures that clusters of autodidacts will fail to achieve intellectual communion by removing the possibility of reading certain things at all.

Yet the officers who destroy books, the politicians who demolish libraries, and the pollsters and technocrats who announce that no one reads are all animated by the same fear: They know that at the heart of reading is the unmastered work of vita activa—the work of one who is comparing, contrasting, translating, and learning, of one who is already relating, participating, and communicating. These guardians know too that, if the reader is enclosed and controlled at the level of the symbol, then those specific readers who might voice a complaint, who might translate their way into visibility within the community, may be thwarted a priori. Words, however slowly and passively read, are faster and more liquid than any currency. This is precisely why words became text, information, data: things allocated by an élite, objects supervised by a police order that is as much a logic as it is a shifting coterie of policemen, politicians, pollsters.

The logic that polices the spectator and reader of art and literature—and therefore art and literature themselves—is wielded as much by artists, novelists, critics, and poets as anyone else; it more often than not manifests in some form of rage or criticism or admonishment directed at the reader en masse. But the policing of art and literature can just as often emerge as a theory, or even an entire strain or school of thought or practice. Contemporary literature’s predilection for harmless social realism, I would argue, is just as much the result of a police logic as mandated Socialist Realism was for the Soviet writer.

Critical theory and philosophy have assimilated this police logic. One way we can tell: aesthetic philosophy has been mostly eliminated from literary discourse. (What is worse, few literary critics seemed to have noticed.) If we take aesthetics to mean the study (or training) of the gaze of the spectator or reader, then the ramifications of this erasure are clear: By removing aesthetics from the equation, the critic or theorist can likewise subtract the reader. More often than not, literary discourse is now pitched as a subset of media theory. There is of course very little place for the reader in media theory, and when she is mentioned at all, it is again as a passive receiver of the “message” of the medium.

✖

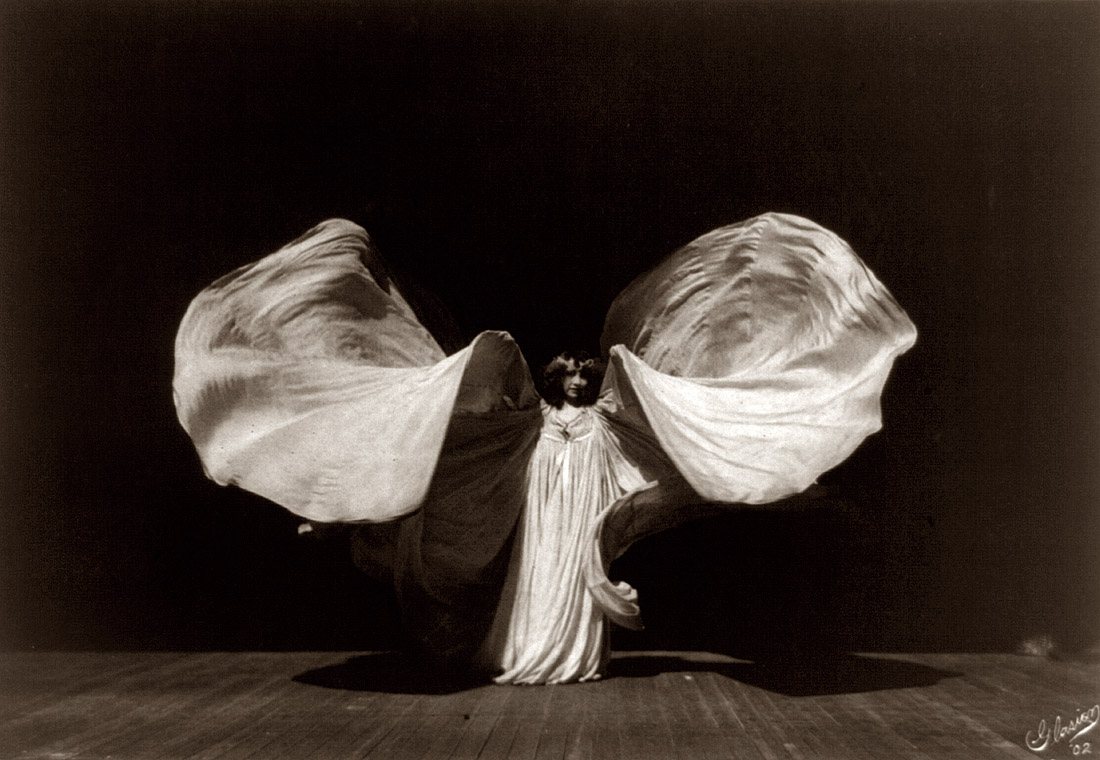

Jacques Rancière’s Aisthesis, the final chapter of which follows this essay, is a work that seeks to return literary discourse to the aesthetic, and more crucially, to return aesthetic discourse to the history of art. Modeled after what is arguably the most important work of literary criticism of the last century, Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis, Rancière’s Aisthesis is no less ambitious: in the fourteen “scenes” that constitute the book, the author not only upends the accepted narratives of the historical development of art, he manages, in the process, to redistribute the role of aesthetics within philosophy and politics.

In Rancière’s historical narrative, the “aesthetic regime of art,” or modern art as we know it, is distinguished from the “representative regime of art,” which predated and at times mixed with the aesthetic regime. The representative regime of art was built upon a hierarchy of societal roles that predetermined who could sensibly be depicted doing what. Aisthesis works to show how the collapse of this hierarchy and the emergence of modern art went hand-in-hand:

Fine arts were the progeny of the so-called liberal arts. The latter were distin-

guished from the mechanical arts because they were the pastime of free men,

men of leisure whose very quality was meant to deter them from seeking too

much perfection in material performances that an artisan or a slave could ac-

complish. Art as such began to exist in the West when this hierarchy of forms

of life began to vacillate. The conditions of this emergence cannot be deduced

from a general concept of art or beauty founded on a global theory of man or

the world, of the subject or being. Such concepts themselves depend upon a

transformation of the forms of sensible experience, of ways of perceiving and

being affected. They formulate a mode of intelligibility out of these reconfig-

urations of experience.

Rancière’s preferred way of showing the historical development of the aesthetic regime of art is the “scene.” As Rancière describes it in his prelude, the scene is a “little optical machine” that weaves together perceptions, affects, names and ideas, constituting the sensible community that these links create, and the intellectual community that makes such weaving thinkable. The scene captures concepts at work, in their relation to the new objects they seek to appropriate, old objects that they try to reconsider, and the patterns they build or transform to this end.

This scene as defined here is a crystallization of Rancière’s broader philosophy. In Aisthesis, as in the rest of Rancière’s work, the “thinkable” or “perceptible” or “sensible” is what determines all political and social possibility. Thus, the artistic process of shifting what can be said, seen, or heard is literally the same as changing what is politically possible; politics and aesthetics are inextricably and materially linked.

Yet the development of art (and politics) is not “aesthetic” because the reader or spectator passively receives the work. Rather, the reader’s material experience contributes to the “sensible fabric” that makes the artist’s “words, shapes, movements and rhythms to be felt and thought as art.” Or as Rancière puts it to the critical theorists and philosophers who would privilege the active artist over the do-nothing reader:

No matter how emphatically some may oppose the event of art and the creative work of artists to this fabric of institutions, practices, affective modes and thought patterns, the latter allow for a form, a burst of colour, an acceleration of rhythm, a pause between words, a movement, or a glimmering surface to be experienced as events and associated with the idea of artistic creation.

The Rancièrean scene is an important formal development, an elaboration and even an improvement on Auerbach’s original. To begin with, each scene—whether it covers film, painting, drama, poetry, or reportage—begins with a critical commentary of an artwork, known or virtually unknown, that manages to split the critic between his double role as reader and writer. As a result, every scene is posed from the outset as a swirl of affective and material modes. When these “optical machines” are taken as a collective unit, it is clear that Rancière’s Aisthesis, like Walter Benjamin’s One-Way Street, is a montage, a string of scenes in succession. In this way, the book itself redistributes the boundaries between forms—in this case, those dividing cinema and literature (although Rancière reminds us that montage actually began with the French novel). This is part of the point for Rancière, for the establishment of artistic modes in the aesthetic age came about as the result of each art “merging its own reasons” with other arts. The specific ways in which artistic forms come up against each other, the way they break down and reform, the redistribution of sensible experience: This is the stuff of the Rancièrean scene.

And so in the chapter that follows, you will find references to photography, modernist and classical literature, little journals, magazine and newspaper reportage, and Romantic poetry. You will also find a philosopher working primarily as a caring reader, not as a passive recipient of a text. In fact, Rancière’s care as a reader often leads him to meticulously rehearse (never paraphrase) the arguments of those he disagrees with, a move that sometimes means that he renders his opponent’s argument more persuasively than they did originally. This form of critique often causes confusion for Rancière’s interlocutors, who are forced to read him as carefully as he has read them.

This is not easily done. Rancière reads so closely because he seeks to consecrate the act of reading, because he wants to show that the reader, like the spectator, can emancipate herself. All writers are first and foremost readers, and it is the right of the reader to assert her equality of intelligence, her capacity to act, upon which all of literature, art, and politics depend. Or as Rancière tells us, by way of his reading of James Agee:

Beyond science and art, beyond the imagined and the revisive, the full state

of consciousness that perceives the “cruel radiance of what is” must still pass

through words.

✖