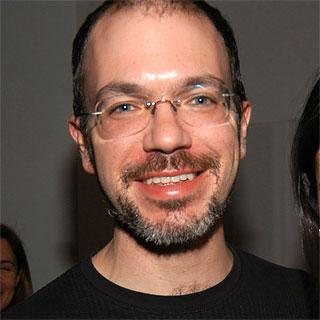

Sasha Frere-Jones, the New Yorker’s pop music critic, often sounds like a guide taking the reader on a tour of some foreign, distant land.

“You could argue that Dr. Dre and Snoop were the most important pop musicians since Bob Dylan and the Beatles,” Frere-Jones once wrote. You could argue that—if Bob Dylan had been a pop musician to begin with, or if Dr. Dre had released more than a single groundbreaking album during his entire career.

It’s almost as though Frere-Jones doesn’t actually expect New Yorker readers to listen to the contemporary music Frere-Jones is writing about. Here’s the critic’s translation of “cocaine rap”: “In these songs, bricks, squares, pies, stones, and yams are coke, and the cooking, mixing, and weighing required to prepare the drug for clients becomes the inspiration for often inscrutable wordplay.” Say what you will about the beats and rhymes, it’s important that the New Yorker’s readership knows that bricks and squares and pies and stones and yams are synonyms for cocaine.

For years, I gave Frere-Jones the benefit of the doubt. I couldn’t argue with that last name, the impeccable pedigree that summoned up the glorious musical heritage of Creole New Orleans. When you’re a young white man it’s tough to disagree with a middle-aged black woman who writes about music, especially African-American music. And Frere-Jones writes about black music a lot.

Frere-Jones frequently harps on the lack of African-American influence in indie music, and once took Stephen Merritt of the Magnetic Fields to task—as only a black woman could—for not including any African-American albums in a playlist for the New York Times. Right on, I thought. Screw that white guy. There’d once been a direct line from Muddy Waters to the Rolling Stones to the Ramones to The Clash, but something had clearly been lost in the translation.

Then, a few years ago, I found out the awful truth. You see, Sasha Frere-Jones is a white man.

Frere-Jones freely confessed this himself. The truth is, he never hid it—I’d merely assumed otherwise. “I’ve spent much of my life playing music, and on and off since 1990 I’ve been a member of a funk band called Ui,” he wrote in the New Yorker in 2007. “We’ve had six members, all white, though most of the musicians who inspire our sound are black.” I dropped my magazine right there. I’d been digesting music criticism from some guy who was in an all-white funk band? Are you kidding?

Musical recommendations I’d gladly accepted from Frere-Jones the Black Woman were suddenly insufferable coming from Frere-Jones the White Man. What right did he have to represent the aggrieved party when he was one of the appropriators himself?

The history of American music, from the blues to jazz to rock to hip-hop, is the history of black musical forms being co-opted and occasionally transformed by white musicians. Until I was thirteen I thought Van Morrison and Stevie Winwood were black—because they sang with soul, something I couldn’t imagine a white person doing. The same rang strangely true for musical criticism: because Frere-Jones wrote so frequently about black music—and so passably—I’d assumed he was black himself.

Frere-Jones’ whiteness made me uneasy. While we readily acknowledge the effect of race on musical expression, we’re much less likely to acknowledge the way in which race affects taste. I want to think that my musical taste is impeccable—that if I were raised on a desert album, and some A&R guy landed a helicopter with Sam Cooke and Barry Manilow on board, I’d be able to tell the difference. Discovering that Sasha Frere-Jones was a white man made me understand that my all-too-carefully curated taste was not as pure and unfiltered as I might have liked.

We’re subconsciously taught to find certain things cooler than others, but any conscious decision to appear cool pretty much instantaneously mutates us into so-called posers. By listening to Frere-Jones the Black Woman but not to Frere-Jones the White Man, I became aware that I’d been consciously taking my cues from African-American culture.

Unlike the enjoyment of music, which is mostly subconscious (“I like that song, so I’m going to listen to it again.”), the consumption of music criticism is a conscious act (“I am going to choose to read and listen to that critic. Let me go buy / download / steal that song / album,” etc.). White America has co-opted so much African-American music that to be caught—by myself, no less!—co-opting black America’s opinions about that music seemed a step too far.

Which leaves me back at square one. I’ve got no choice but to make my peace with Frere-Jones if I’m to believe that my taste is at least somewhat organic. The truth is, white man or black woman, Frere-Jones is a music geek in the best sense. Sure, he’s a little pedantic, and occasionally grievously wrong, but I suppose that’s all part of the game.

✖