The secret to John Updike’s long tenure as America’s preeminent man of letters can be found in the essays from Self-Consciousness, his 1989 memoir-of-sorts. The book is fairly representative: it’s an unabashed hymn to Updikehood, a finely recorded bout of nostalgia, a cheerful philosophical riff, and a masterwork of English prose. To Updike’s critics, the memoir reads like an exercise in self-indulgence. James Wood claimed it was easier for Updike to “stifle a yawn than refrain from writing a book.” His fans, however, find it enchanting. The author’s memories awaken us to the treasures hiding in plain sight—the equivalent of glimpsing a coral reef in an otherwise mossy small-town pond. Pennsylvania grade school, Christian prayer, TV jingles, doubts, desires—he wrote about anything he considered “synonymous with being.” “Being” was Updike’s primary muse, the subtext to every whimsical theme. Sex, basketball, marriage, golf, middle-class America—each was just an excuse to explore the alien joy of being alive, and the desire to have it go on forever:

My mind when I was a boy of ten or eleven sent up its silent scream at the thought of future aeons—at the thought of the cosmic party going on without me. The yearning for an afterlife is the opposite of selfish: it is love and praise of the world that we are privileged, in this complex interval of light, to witness and experience.

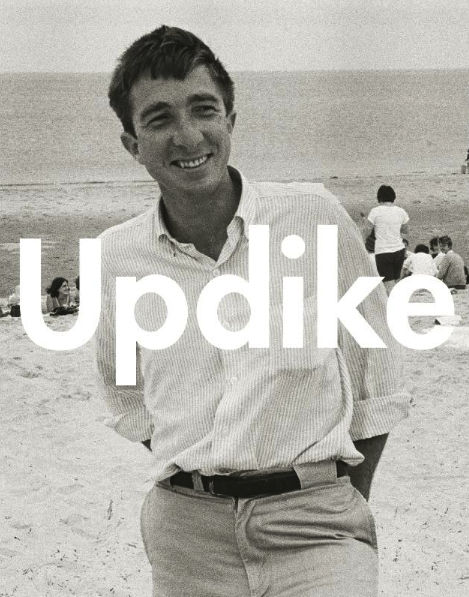

Having learned of the Christian afterlife from the pastors at Grace Lutheran Church in Shillington, Pa.—his hometown and the basis for his go-to fictional burg, Olinger—Updike spent the next sixty years pursuing the immortality of print. In his new biography, Updike, Adam Begley makes an insightful connection between the author’s customized faith and his famous productivity. According to Begley, Updike—at a very early age—“accepted the blessing of a sometimes puzzling but generally benign deity,” a blessing that gave him artistic courage and license to write about anything with the same wonder and verve. His faith was real and significant. A committed Lutheran in his twenties, he challenged the Unitarianism of his father-in-law and grappled with Protestant intellectuals Karl Barth and Paul Tillich. It was also, however, strategic. Updike’s religion was permissive, unlike the haunted theologies that sharpened the fiction of Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, or Graham Green. “Having accepted that old Shillington blessing,” Updike once wrote, “I have felt free to describe life as accurately as I could, with especial attention to human erosions and betrayals.” Of Updike religiosity, Begley writes, “he’s claiming divine sanction for his autobiographical impulse.”

The autobiographical impulse is the key to the Updike canon, and Begley does an excellent job of tracing its evolution. Updike’s purpose was never to get at the essence of life through human drama; instead, he tried to “transform, with a lively accuracy, some piece of experienced reality to the printed page.” Laughter, snowfall, a woman’s calf—for Updike, these were all part of the “tremor of actuality”; his job was to register human sensations as dutifully as possible. His settings and characters, of course, appealed to a limited demographic; this was inevitable from the start. As Begley puts it: “The more Updike one reads, and the more one learns about his life, the more glaringly obvious it becomes that he was enthralled by the details of his own experience.” Call it narcissism or call it art; either way, it can’t be anything in between. Updike himself had made his peace with the risks of submitting to the thrall. When lawyers advised him to censor some of the racier parts of Rabbit, Run or scramble the characters in Couples, he complied without much trouble, but he never allowed the “narcissist” label to keep him from mining his cherished past. For him, the germinating principle of art was “pleasure, but not egotistical pleasure, or at least a form of egoism that is useful to others.” Over time, he believed, writers should aspire to “become less and transmit more.” As for the public’s reaction, he was sensitive but unrelenting; his attitude is summarized best in a critical essay on reading Proust: “a personal obsession,” he wrote, “should not be confused with an artistic one.”

When Begley takes on the difficult task of settling this confusion, we learn that Updike’s artistic ambition was a multifaceted thing. At first, he wanted to be a cartoonist (apparently, even in middle age, he could sketch Mickey Mouse from memory). Then, he thought, a painter. Soon after college, he realized that his chief talent was writing. From Proust, he learned that the artistic impulse was a variant of the religious one (“his sentences seek out an essence so fine the search itself is an act of faith”), which meant that literature—whether it took as its subject wife-swapping or farm labor—was always a cosmic endeavor. His style emerged in a few short years. Initially under the spell of Hemingway and Salinger, he began to see that “clarity and logicality are not the only virtues of prose.” Like Joyce, he wanted to “explore the margins where mental processes surrender grammar.” Like Henry Green, whose novels Updike discovered during a year in England, he wanted to loosen his syntax, make his metaphors more striking. Both Proust and Green would remain his two non-American touchstones. He saw them as artists in the modernist tradition, where the “vast datum” of life’s material is processed and encrypted. These authors, he wrote, “showed me what words could do, in bringing reality up tight against the skin of the paper.” In a career that spanned over half a century, Updike produced more than twenty novels, hundreds of stories and poems, and three hefty volumes filled with essays, criticism, and literary sermons. He had learned from Proust how to write, as he says, “with a whole new nervous system.”

✖

First, he became a New Yorker writer, an ambition of his since adolescence. As Begley reveals, Updike’s fame was tied to the magazine: “critics identified Updike as a typical New Yorker writer, as though he had been concocted in-house, the product of a singularly fruitful editorial meeting.” Though he made a lasting impression—not one of his “Talk of the Town” pieces was ever rejected—he worried about displaying a “contemptuous harried virtuosity,” and he wondered about his need to reach the “metropolitan-minded” reader. Eventually, he moved to the town of Ipswich, putting a reasonable distance between himself and the wordsmiths of Midtown. Still, the city dazzled him. In a 1968 interview with Time magazine, Updike admitted to having “a sneaking fondness for elegance, for people whose apartments are full of money and whose martinis come all dewy and chilled.” Fortunately there was something more to Updike’s experience of New York, as he hints later on in the interview:

There’s a certain moment of jubilant mortality that you get on a Manhattan street—you know, all these people in the sunshine, all these nifty girls with their knees showing, these cops, these dope addicts, everybody swinging along, and they’re never going to be in the same pattern again and tomorrow a few of them will be dead and eventually we’ll all be dead. But there’s a wonderful gay defiance that you feel in New York in the daytime.

Though he would soon transition from elegant hack to serious novelist, Updike retained that “gay defiance” in the face of mortal angst. Above all, he was determined to praise, and to offer his readers higher pleasure. “The creative imagination wants to please as it has been pleased,” he wrote. “Description expresses love.”

Unlike Salinger, Mailer, and Vonnegut, all traumatized veterans, Updike had milder issues to deal with: a case of psoriasis and a stutter. Given his basically Christian worldview, the loss of innocence that shocked Salinger was, for Updike, part of the plan (it helped that he didn’t experience D-Day). Still, it was easy to write him off as a gorgeous but insignificant writer. Christopher Lasch, his roommate at Harvard (where Updike worked at the famous Lampoon), liked to describe him as merely “a humorist.” And at least in the early days, he was. He liked to imitate James Thurber; he admired P.G. Wodehouse. In time, he became a serious critic, though he wasn’t much of a scholar. Lasch wrote his senior thesis on the rise of American imperialism; Updike’s subject was less straightforward: “Non-Horatian Elements in Herrick’s Echoes of Horace.” It didn’t cause a sensation, but it left him with an important insight. Herrick, he wrote, “is willing to describe tiny phenomena with the full attention and sympathy due to a major theme.”

His implicit faith in America, and his desire to live an ordinary life, meant that his novels would lack the edge of Roth’s or Bellow’s or Gaddis’s. As Begley points out, he learned from Salinger “how to smuggle religion into short stories,” but he wanted to strike a sunnier note than his tragic, Buddhist peer. He explained as much in a letter to his mother. “We need a writer who desires both to be great and to be popular,” he wrote, “an author who can see America as clearly as Sinclair Lewis, but, unlike Lewis, is willing to take it to his bosom.” Much as he admired John Cheever, he couldn’t stomach the pessimism. When Cheever’s “O Youth and Beauty!” appeared in the New Yorker in 1953, Updike said “it tasted as rasping and sour as a belt of straight bourbon. I thought to myself, ‘There must be more to American life than this.’” Harry Angstrom of the Rabbit trilogy gave Updike the chance to fill in the picture. “What I saw through Rabbit’s eyes, he wrote, “was more worth telling than what I saw through my own.”

A proud Pennsylvanian, Updike was always looking for ways to write himself into the state’s legacy. He found a kindred spirit in the “journeyman printer” Benjamin Franklin. Both sought after “moral Perfection” despite their many sins, both were engaged in “an intellectual form of manufacture,” and both had a fetish for ink and parchment. (The difference is that Updike’s politics remained typographical. In 1954, he exchanged manifestos over punctuation with his editor Katharine White: “The colon suggests the Bible: the dash letters and memoirs of fashionable ladies.”) The other statesman from Pennsylvania was former president James Buchanan, about whom Updike was always threatening to write a historical novel (in the end, he wrote a forgettable play, proving, to the delight of many, that he could fail in at least one genre). Then, of course, there was Wallace Stevens, a native of Reading, Pa. and a fellow Harvard alum, whom Updike praised for his “endless willingness to consider things metaphysically.” The doyen of American letters never forgot his small-town roots. When the public was flummoxed by Andy Warhol, Updike recognized the type: a pasty kid from Pittsburgh trying to make a splash in New York City.

When it came to fiction, Updike favored the realist vision of William Dean Howells, an Ohio native who escaped to the East and became America’s wealthiest writer. Against the realism of Sinclair Lewis, the kind that exposed unpleasant truths, Updike praised Howells for trying to capture the essence of “average” American life. Among the national pantheon, he was more attracted to Melville’s earthiness and Hawthorne’s visceral Puritanism than to Emerson’s lofty ideals. Ever loyal to the tactile world—to the infinite flux of human sensation—Updike mistrusted what Henry James called “the superstition of form”: the idea that plot and character create an algorithm of meaning. In an essay on Howells, he writes: “But what if a story is not therapy—not an antidote to life but a clarification of it? What if you think the narrative art derives its value and importance from its patient truthfulness to our mundane human condition?”

His occasional sparring with Tom Wolfe reinforced this aesthetic creed. (He was repelled by the “icy-hearted satire” of Bonfire of the Vanities, and he wrote that A Man in Full “amounts to entertainment, not literature.”) Wolfe is a Sinclair Lewis-type realist, a sociologist with a knack for drama; Updike was always more interested in the human individual. In 1985, he made a bold claim in the pages of Esquire. “Fiction,” he wrote, “is nothing less than the subtlest instrument for self-examination and self-display that Mankind has ever invented.”

Despite the evident consolation Updike found in Christianity, religion wasn’t subtle enough to answer his need for self-display. In the final essay of Self-Consciousness, “On Being a Self Forever,’’ he offers a candid account of his faith: “one believes, not merely to dismiss from one’s life a degrading and immobilizing fear of death, but to possess that Archimedean point outside the world from which to move the world.” In other words, believers can get through the day without too much existential fuss. Updike was grateful to Irish Murdoch for “trying to rescue religion from an intellectually embarrassing theism.” And yet he resisted Annie Dillard’s “flirtations with the absolute.” Dillard, he felt, was too experimental— her spare, quietly rapturous prose was breaking rules he had worked hard to learn. If writing was not a mechanical process resulting in one of four genres—reliable as states of matter—Updike could not go on being Updike, clacking away at his desk. It was necessary for him to believe his craft was an ordinary thing—like dentistry, but with pen and paper; like chemistry, but without the lab. His consistent praise for Stephen Jay Gould is telling in this regard. Yes, Gould’s essays on evolution are deep and illuminating. Updike, though, is most impressed that his colleague “never missed a deadline.”

✖

Famous for extramarital sex, Updike was more specifically concerned with how Eros encodes itself in the lives of “blundering mortals.” Begley does well to track his subject’s views on the matter over time, which culminate in Updike’s response to Rougemont’s Love in the Western World, a landmark study of romantic affairs. The scholarly work taught Updike that erotic love was symbolic—“a kind of code for all the nebulous, perishable sensations which we persist in thinking of as living”—and it gave him another useful insight that made its way into fiction: “a man in love ceases to fear death.” If sex is a heightened form of living, and living is Updike’s muse, then why not write about sex as explicitly as one writes about everything else? This was Updike’s take on the matter; critics had other ideas. Already mocked for being prolific, stylish and superficial, Updike the wistful misogynist was an easy target for younger authors. Of course, there were other faults to expose. He often expressed ambivalent views about the Vietnam War, which made him sound like a government stooge at cocktail hour on Martha’s Vineyard. Essentially, though, he was apolitical, which some critics think is crime enough. (Otherwise, his nostalgia for the country of his youth was interpreted as conservatism). Begley is quick to defend Updike from those who consider him out of touch, an accusation that gathered momentum after the publication of Terrorist. (Having been criticized for writing about the familiar, “he was now told he had no business imagining the interior life of a Muslim teenager.”) Where Updike’s detractors see purple prose, Begley sees “baroque splendor.” And in response to Professor John Alderidge, who leveled the famous terse rebuke—“Mr. Updike has nothing to say”—Begley quotes the man himself on the appropriate reaction to bad reviews: “…in the end, the next day dawns with its sunburst of blank paper, and the enterprise of composition itself, with its grand intention of bringing a piece of reality over into print, overrules the keenest self-doubts and the most venomous sneers.”

A critic himself, Updike was a voracious, principled reader. Still, he had no time for those who disrespected their readers. (Of Roland Barthes, he wrote: “S/Z is a nearly unreadable book about reading…he seems often to be recapitulating something we should have read elsewhere but haven’t.”) Nor did he respect the idea of writers as politicians. Thinking of Vargas Llosa, Mailer, and Vidal, he could not understand “why anyone with an opportunity to create imperishable texts would want to exhaust his body and fry his brain in the daily sizzle of power brokerage lies quite beyond my own imagining.” His criticism is most revealing when it addresses the problem of alter egos. Some writers loved their creations too much (“Salinger loves the Glasses more than God loves them”); others not enough (in a review of Don Delillo’s Players, Updike wrote: “the drastic unlovableness of Lyle and the very tepid appeal of Pammy discourage the considerable suspension of disbelief necessary to follow them into their adventures.”) A lifelong fan of Nabokov, Updike understood the Russian’s need for “metaphors of personal history.” He himself had three avatars: Richard Maple (Family Man), Henry Bech (New York Writer), and Harry Angstrom (American).

Yet Updike often didn’t need the mask of a fictional narrator. “In Football Season” –a litmus test for the Updike novice—is three short pages of pure nostalgia, a single unbroken reverie:

The stadium each Friday night when we played was filled. No only students and parents came but spectators unconnected with any school, and the money left over when the stadium rent was paid supported our entire athletic program. I remember the smell of grass crushed by footsteps behind the end zones. The smell was more vivid than that of a meadow, and in the blue electric glare the green vibrated as if excited, like a child, by being allowed up late. I remember my father taking tickets at the far corner of the wall, wedged into a tiny wooden booth that made him seem somewhat magical, like a troll.

The town has been renamed, but the rest is likely straight from memory. Updike transports personal memory into the realm of myth, offering readers a lasting pang of genuine human sensation. The question is whether this is enough. For many of us, it is. The writer who describes a pencil as “a rod of agglutinated graphite” is maybe a bit of a show-off. But the writer who gave us the floodlit end zone is putting that nervous system to use. Updike may have peered out from a few too many dust jackets, and the twinkle in his eye may not match the fangs in his smile. Still, to dismiss him on grounds of self-indulgence is to misunderstand the magic of fiction.

✖