Materializing ‘Six Years’ is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through February 17.

✖

There is an exhibition now on view at the Brooklyn Museum called Materializing ‘Six Years’ which, without meaning to, makes a case for one of the unacknowledged literary movements of the twentieth century.

For I am convinced that it was a literary movement: a group of writers, theorists, and editors who were all working through the same set of problems in the late ’60s and early ’70s. It’s just that they weren’t called writers, or theorists, or editors. Instead, they were called “conceptual artists,” both by themselves and by their chronicler and collaborator, Lucy Lippard, who herself is usually termed a “critic.” Lippard has said that she dislikes being called a “critic,” since the word implies an adversarial relationship to artists. But she has been equally resistant to being classed as an artist in her own right. Remembering her activities in the late ’60s and early ’70s, the period covered by her influential book Six Years (1973), Lippard writes, “When I was accused of becoming an artist, I replied that I was just doing criticism, even if it took unexpected forms.”

It’s easy to see why Lippard’s activities as a critic and curator were sometimes confused with the work of the Conceptual artists. As is amply illustrated by Six Years (whose encyclopedic, chronological structure is the backbone of the Brooklyn Museum show), Conceptual art was a project to dematerialize the art object—to make art that was emphatically and undeniably “about” something beyond its material appurtenances. Put like that, of course, it doesn’t even sound radical; most art that has ever been made seeks to exceed its materiality in some way, to denote, to connote. But the conceptual artists were more ruthless about it, more willing to force their point. This meant doing away with many of the usual pleasures, such as strong use of color, high technique, striking composition, and so on. Conceptual art is essentially literary in character: as Lippard puts it, it is “work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary, lightweight, ephemeral, cheap, unpretentious, and/or ‘dematerialized.’”

In curating art that was oriented towards process rather than product, Lippard was often heavily implicated in the works’ authorship. One of the displays in the Brooklyn Museum show is a page of notes sent to Lippard by the artist Seth Siegelaub, briefly detailing how to make one of his pieces. For exhibitions she curated in Seattle, Vancouver, and Buenos Aires in the late ’60s, Lippard constructed several artists’ outdoor pieces herself, according to basic instructions like Siegelaub’s. Budget constraints (not enough money to fly out the artists) was the reason for this arrangement, although it is indicative of the Conceptualists’ outlook that they had no problem with Lippard making their works; the idea was paramount, the execution secondary (Sol LeWitt in Artforum around this time: “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art”). Another display in the show is a piece of paper that bears a typewritten narrative by the performance artist Vito Acconci, who incidentally began his career as a poet: “Private piece for Lucy Lippard (Nov. 16, 1969; city series): Follow-up to an activity situation using streets, travelling, following, changing location… […] October 16: I neglected to follow anyone. November 16: The particular activity re-activated for Lucy Lippard.”

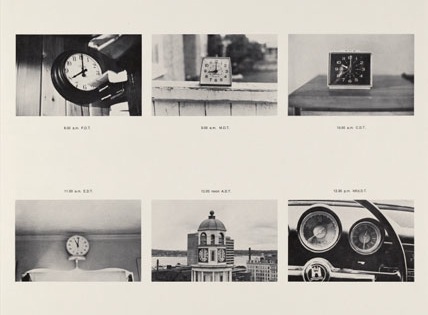

Unsurprisingly, a museum show about dematerialized art is nothing much to look at. Most of the items on display are unlovely, plain, rubbishy-looking; there’s little to no chance that you will be seduced by their materiality, and that’s the point. In fact, the viewer of this show is not so much looking as reading. Sure, there are diagrams and drawings and even the odd video or sound recording, but most of the stuff here is ephemera: there are a lot of sheets of letter paper, covered in typewritten or handwritten procedures, data, and notes. Having banished formal concerns, the Conceptualists used information and systems “the way a rectangular format is laid over the seen in paintings, for focus” (Lippard).

Unlike most museum shows, where captions can and maybe should be ignored, this is an exhibition where narrative is essential. Everything you see is a referent, often to performance pieces or installations that have no abiding material trace beyond a description on a piece of paper, or a pencil drawing of its planning, or a few snapshots. Notable outliers are works that privilege concept but insist on a subtle materiality, such as Hanne Darboven’s delicate “permutational drawings,” or Agitprop pieces like the infamous Art Workers’ Coalition poster that juxtaposed a photo of the My Lai massacre with the text, “Q: And babies? A: And babies.” Some of the works were print-based to begin with, like a front-page classified ad placed by artist Joseph Kosuth (a limited edition work defined by the entire run of newspapers carrying the ad), or Douglas Huebler’s 1969 artwork consisting of a signed and dated letter guaranteeing a reward, to be paid by the artist, for information leading to the arrest of a certain bank robber. By comparison, the few Minimalist works on display—a Robert Ryman painting on six sheets of paper, an Alice Adams sculpture made of aluminum fencing—look positively sensual.

Exhibitions about artistic and political movements tend to be anticlimactic in a way that solo retrospectives aren’t. The sense of urgency that attends a moment of collective thinking, that feeling of “we, together, are creating something new,” is easy to lose in the long view. The current Brooklyn Museum show is no exception to this deflating tendency—in fact, it is singularly lacking in exuberance, even among art historical retrospectives. Certainly, in constructing a clear and sympathetic context for the art, it underperforms compared to the book on which it is based.

Six Years is an idiosyncratic chronicle of the Conceptual Art movement from 1966 to 1972, and Lippard is both a protagonist and chronicler of the story. She cops to this double involvement with an easy, honest manner in the preface, freely disclosing the personal relationships, political influences, and life circumstances that caused her to fall in with the Conceptualists. Her early life in the New York art world sounds like the setup for a novel, or at least a terrific memoir: she recalls that she, her then-husband (Robert Ryman), and one of her best friends (Sol LeWitt) “all worked at The Museum of Modern of Art in the late fifties. Ryman was a guard; LeWitt was at the night desk; I was a page in the library.” More impressive still are her faithful quotations of her opinions from that time, even ones she no longer holds, and her ready admission of her own poorly received attempts to bridge art and writing: “I was writing abstract, conceptual ‘fiction’ then; at one point I tried alternating pictorial and verbal ‘paragraphs’ in a narrative; nobody got it.” Later, she continued to experiment with written form, making exhibition catalogues and entries from shuffle-able packs of index cards and randomly chosen dictionary excerpts.

Lippard doesn’t lack a sense of humor, which is part of why Six Years, against all odds, is an entertaining read. And she is an excellent writer. But more than anything else, it is the restless, conscientious, and systematic intellect she brings to bear on Conceptual Art that makes her its most reliable narrator. This bent of mind is immediately evident in Six Years, starting with its frankly exhausting full title: Six Years: The dematerialization of the art object from 1966 to 1972: a cross-reference book of information on some esthetic boundaries: consisting of a bibliography into which are inserted a fragmented text, art works, documents, interviews, and symposia, arranged chronologically and focused on so-called conceptual or information or idea art with mentions of such vaguely designated areas as minimal, anti-form, systems, earth, or process art, occurring now in the Americas, Europe, England, Australia, and Asia (with occasional political overtones), edited and annotated by Lucy R. Lippard.

That long and masterfully punctuated title is the kind of weird gesture that really works with Conceptual art, and it’s also a good example of why there was no chance that the Brooklyn Museum show, a faithful stage adaptation of Six Years, could convey what the book does. Ultimately, in showing what these artists were doing, a written narrative is more appropriate than a roomful of artifacts. It’s not that Lippard portrays the early Conceptualists in a particularly romantic or dramatic way, or strains to trace common themes and compulsions they shared. She simply catalogues their work, with scrupulous and sometimes tedious detail. Turning the (many) pages of Six Years yields a picture of a populous, international, and diverse group of artists united primarily by their modest non-acceptance of art world convention—an ignoring of the prevailing norms and a willful blindness to certain visual expectations. It’s a story worth reading, and you can skim the pictures.

✖