Pantheon · 288pp · $26 · 16 October 2012

The virtue of experimentalism is to make even failure noble. It is in this spirit that we should assess the most recent book by veteran experimentalist Mark Z. Danielewski, The Fifty Year Sword (2012). The book takes place at a late-night party in East Texas. Chintana, a Thai seamstress recently divorced by her unfaithful husband, unexpectedly comes to supervise the telling of a grotesque story by a sinister storyteller before an audience of five orphans. Its terrible dénouement may destroy them all. Like Mr. Danielewski’s previous two books, The Fifty Year Sword represents a significant departure from the look and feel of a traditional novel.

Mr. Danielewski’s first book, House of Leaves (2000), was a brilliant, layered mélange of genres and voices constructed around the central conceit of a physically impossible house whose ordinary exterior belies an always altering, treacherous, oversized interior—a house quite possibly meant to embody the set of dislocations claimed by postmodern literary theorists to lie at the heart of language itself. His second book, Only Revolutions (2006), was a whimsical and intricate—verging, perhaps, on maudlin and precious—story of a world-historic, teenage love affair told from both perspectives starting from opposite ends of the book. The Fifty Year Sword more closely resembles Only Revolutions than it does House of Leaves: both novels make especially prominent use of colored typography and non-standard orthography (e.g., “predespotician,” “indacitate,” “fortipify”), they adhere to a single, easy-to-understand narrative scheme throughout (in contrast to the ever evolving schemes of House of Leaves), and they employ a mythic or fairy-tale poetics (in contrast to the hysterical realism of House of Leaves).

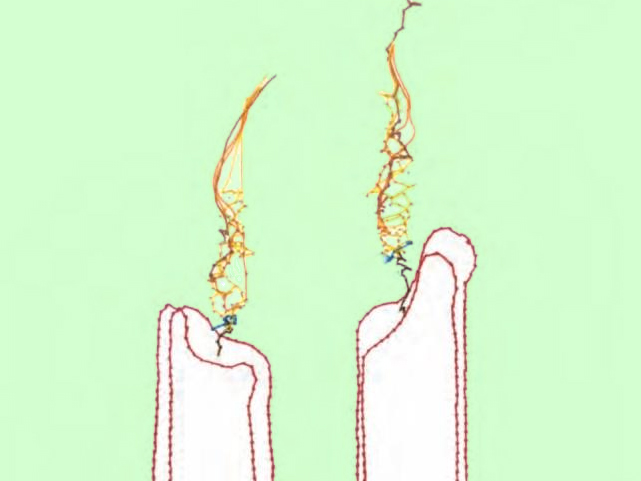

The Fifty Year Sword is not exactly appearing for the first time—it has circulated for several years as a large-size limited edition in Dutch and English. In addition, Mr. Danielewski has performed The Fifty Year Sword as a “live shadow show” once a year on Halloween night (according to press materials). The new edition from Pantheon, intended for mass consumption, also includes “newly stitched illustrations and autumnal quotation marks”—these are the work of Atelier Z, a design group founded by Mr. Danielewski.

✖

The so-called “autumnal quotation marks” appear in one of five different “autumnal” colors and assign the text they enclose to one of five distinct narrators. Mr. Danielewski himself claims, qua author, to have done no “more than lend together these gathered and rerelated bits,” which come from “independently conducted interviews”; on the title page, a cloud of autumnal quotation marks even replaces the author’s name. (In this, Mr. Danielewski adopts the same author-as-editor pose familiar from House of Leaves.) This scheme renders the book basically unquotable: readers beware, quotations from the book in this review may appear drastically different in situ.

However, while the device itself of stitching together multiple perspectives into a single linear narrative, exemplified by Virginia Woolf’s masterpiece, The Waves (1931), is a perfectly respectable one, its use in this case does not contribute to any especially visible form of harmony or dissonance (apart from certain halting rhythms) among the narrators—none of whom, in any case, ever emerges sufficiently characterized so as to permit a mode of distinction other than by autumnal color. What’s worse, sometimes the narrators alternate so rapidly—e.g., every couple of words—that the reader must elide the quotation marks intended to set off their respective contributions. This unavoidable contingency converts Mr. Danielewski’s scheme into a dead letter by making invisible the very narrative sutures Mr. Danielewski sought to make visible in the first place. Ultimately, the autumnal quotation marks function more effectively as a decorative scheme imbuing each page with a splash of russet, eggplant, and lemon yellow than they function as an experimental device.

Mr. Danielewski enjoys more success elsewhere. The text of the narrative, splayed by design across each page in a Mallarmé-esque fashion, intermingles with the stitched illustrations: the page is transformed from a mere container for text into a pictorial or graphical space in its own right. Furthermore, the very abundance of blank pages works to align the temporality of the narrative with that of its reading: the de facto “waits” of the blank pages give rise to a phenomenology of suspenseful reading. Finally, the blank pages, in their immaculate eggshell whiteness, often form a pleasant contrast with the riot of color facing them.

The stitched illustrations, more often abstract than mimetic, make up perhaps the most interesting part of The Fifty Year Sword. They intrude upon the page like the dire ganglia of some malign intelligence. At times, they even overwhelm the text itself, supplanting it in several multipage, multi-color, ecstatic, graphical sequences. Yet their very gorgeousness may endanger the work by threatening to reduce the articulate density of text to the mute condition of an objet d’art.

✖

More than just a key formal element, stitching also provides the book with its central metaphor. The Fifty Year Sword stages no less than the cosmic showdown between the seething, destructive energies of violence and the reparative, connective power of stitching. This conflict extends to memory, trauma, and revenge—important elements of the plot—in an essential way. Chintana, infuriated by the multitude of casual ways she is forced to acknowledge her recent divorce (including the role played in it by the odious adulteress, Belinda Kite), broods upon yet more violence (“to lash across the throat”) as a form of meager consolation for the pain of her own trauma (“only infliction promised her peace”). A brutal injury she accidentally received from her own scissors (“metal V wedged deep into her soft thumb”) shortly after the divorce serves as a physical reminder of her emotional pain.