I.

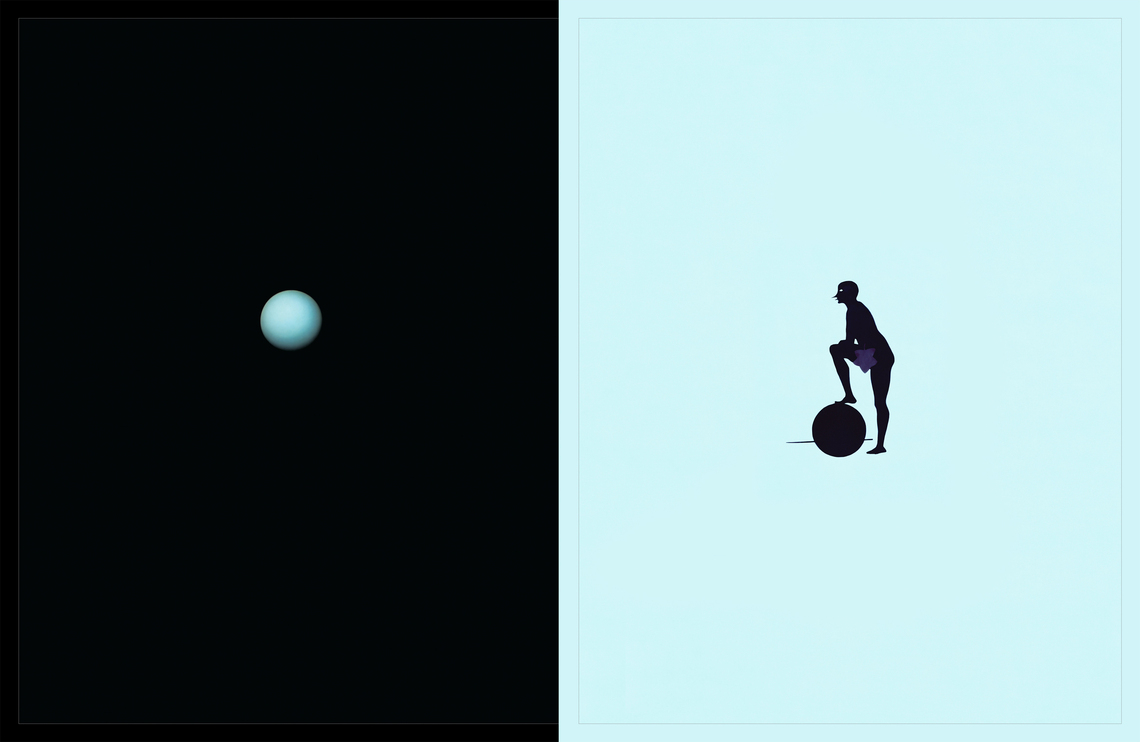

After hours of wafting through the Whitney Biennial last spring, I was startled to find a piece on the top floor that grounded me: a dichromatic print divided in two called Regarding Venus (2012). The left half was all black, except for a small, Tiffany blue sphere. The right half was blue, this same shade of Tiffany blue, except for a small, black silhouette of what looked to me like a commedia Pantalone—the miserly lech—with his foot planted on a circle the same size as the sphere on the left. A purple leaf covered his crotch. Was it a photograph, a painting, a collage—or some combination of all three?

I stood in front of it for forty minutes, thinking, until the museum closed.

The piece is by photographer Sarah Charlesworth, who, just before the exhibition, had died of an aneurysm at sixty-six. Regarding Venus introduced me to her work, but I’ve since found that she left a rich and progressive body of artwork spanning forty years.

I read later that Charlesworth had cut the outline of the figure from Francis Picabia’s 1922 painting The Fig-Leaf, a jab at the era’s excessive censorship. Pacabia himself had borrowed the figure’s pose from J.A.D. Ingres’s painting Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864). In Ingres’s painting, the breasts of the Sphinx are eye-level with Oedipus, his gaze locked onto the right nipple. A shadow covers the Sphinx’s head so that, at first glance, the painting seems to show a naked man gesturing to a floating, illuminated tit. With these layers in mind, Charlesworth aligns the gaze of Pacabia’s pervy Pantalone on the right with the photograph of the planet Venus—a floating, illuminated ball—on the left. Add the alluring blue, and the piece arrives. The piece continues to arrive and to arrive, really.

I would never have made connections with Picabia and Ingres on my own, though my eyes did shuttle between, on the left, the planet Venus and, on the right, the dirty old man with his foot cocked on a dark hole, as if conquered. (Yes, I thought, frowning, regarding Venus.) The piece isn’t that easy, though. It’s not a quick, hot rant, but a slow, cool consideration.

What about Regarding Venus transfixed me? Well, the title certainly invites meditation, a hard think in the vein of Montaigne—“Of Beauty,” maybe, or astronomy or erotic desire. And the clean, black lines against Tiffany blue had lured me from across the room. But it was the simple and piercing construction that held me. More than any element, what united—and, oddly, complicated—these ideas for me was form. The piece is divided in two, distinctly separated, a perfect symmetry. The piece is a diptych.

Generally, a diptych is two panels of equal size joined together by some device, usually a hinge. The form follows a long tradition that began in late Western antiquity, when Romans appointed to the consulate in the 4th – 6th centuries A.D. commissioned ivory tablets carved with their own likenesses on each panel (before we criticize smartphone selfies as a symptom of contemporary narcissism, we might look first to our uncanny doppelgangers, the Ancient Romans). The tablets were connected by a hinge, and closed like a book to protect the inside—a thin layer of cool wax where the consul could write with a stylus and, if necessary, erase. The diptych was, essentially, a ceremonial notebook used to track and record consular appointments by year. When, in the next few centuries, the consular diptychs were reused by the early Christians, the insides of the tablets were erased and used to record prayers for the living church community in Western Europe. In Eastern Europe, they were used to record prayers for the dead. Elsewhere, the ivory tablets were used to keep track of the growing list of saints and their appointments by year. (The early history of the diptych, then, is history itself.)

The rise of iconography in the Christian church evolved the diptych into a narrative form. A scene—most often the birth, crucifixion, or resurrection of Jesus—was painted on one panel and hinged to another. Larger diptychs could be slightly closed to stand on the altar of a side chapel; smaller diptychs could be shut and carried, the paintings inside protected by the decorative casing. Narrating complex stories from the New Testament to illiterate Christians, these diptychs worked much like stained glass windows would in later cathedrals.

The narratives of the New Testament are filled with paradox—Christ is both fully human and fully divine, both dead and alive—and the diptych offered reconciliation. Two stories, set parallel and given equal weight, merge into one, and the hinge offers a moment to chart similarities and differences. The iconic diptychs also became holy objects themselves, capable of healing and calming the mind. A meditation on the two panels could bring one closer to God.

Many contemporary visual artists besides Charlesworth have harnessed this power of the diptych. Jasper Johns’s In Memory of My Feelings—Frank O’Hara is two panels swirling with gray and hooked with a hinge, an appropriate form for the collaborative piece (the name is taken from a poem by Frank O’Hara). Andy Warhol’s Marilyn Diptych shows, on the left, a color repetition of the well-known portrait of Monroe and, on the right, the same image in black and white that fades toward the edge. This is a far more striking piece, for me, than his far more famous, solitary portrait of the actress. Warhol made Marilyn Diptych in 1962, the same year Monroe died. Each panel haunts the other, and they throw energy back and forth like a perpetual motion machine.

This perpetual motion drives the diptych. A dialogue emerges, something like a silent Platonic dialogue, in which ideas are presented, expounded with evidence, challenged, and left unresolved. The diptych is a wrestling.

In the traditional triptych (which has a similar, parallel history), the central panel is twice as wide as the side panels, which close like window shutters. What matters most is the “light”—the glinting gold and silver scene—from the central window. The shutters are hinged to, and entirely dependent upon, their window. The central panel holds the most weight, as if it were the synthesis between thesis and antithesis. The idea is more singular, more unified or complete, a kind of variation on a single theme exhausted through three attempts. In a way, we can often view the triptych as a secret portrait that, with the viewer, collapses three panels—a beginning, middle, and end—into one idea. One of our best painters in recent memory was a frequent triptychist—Francis Bacon—and his three-fold works never fail to stun me. Though sometimes moving, I find the triptych less inquisitive than the diptych. It’s as if the artist has done the work for you and has displayed it for your viewing pleasure. It is your job, then, to uncover the journey. We are too fluent with the logic of the Hegelian dialectic. What I am fascinated by is the dialogue. Whereas the triptych collapses, the diptych expands.

And yet, there is no escaping the strength of the number three. A triangle is the sturdiest shape in architecture. The Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome, the pyramids, the molecular structure of diamond—all derive their stability from the strength of three. Comedy has the “rule of three,” that a joke is funnier in a repetition of three, with the punchline falling on the third. And of course, the Christian Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Ghost—a holy triptych that collapses into one idea: God. The diptych can’t escape this rule of three, and perhaps this is also part of its power. Just as the triptych is secretly a portrait, the diptych is, in a sense, a triptych. In our hunger for three, the two panels of the diptych begin an investigation that must continue in the viewer, whose mind becomes the third, middle, focal panel. The transaction is silent, but the viewer receives responsibility in the investigation. The viewer is needed. The viewer completes the diptych. The viewer of the diptych becomes maker.

I would like to praise this ancient form, the diptych, for its ability to encourage collaboration and resist a passive viewing.

II.

In his introduction to Jean Genet’s The Maids, Jean-Paul Sartre writes, “Whereas the unity of the mind is constantly haunted by a phantom duality, the dyad of the maids is, on the contrary, haunted by a phantom of unity.” The ghost of marriage floats around the form of the diptych, two bodies distinct but joined in a unified vision. Each time we attempt to embrace this familiar shadow of reconciliation, however, like in the ancient epics, the shade escapes our grasp, and the diptych remains split.

So far, I’ve defined the diptych entirely in terms of visual work, both in medieval icons and contemporary works like Regarding Venus. But this form can be applied—and is applied, increasingly—with great effect to narrative works, such as books, essays, performances, and films. Because we’re not expecting it, because the diptych hasn’t yet become a tired form in narrative, I think the diptych challenges and transforms traditional narrative, that is, story built around the arc of beginning, middle, and end.

The major difference between the visual and the narrative diptych is that the latter presents an inevitable order. (It’s interesting to note that theatre comes with this built-in structure, Act One and Act Two, separated by an intermission, but rarely uses the intermission as more than an arbitrary bathroom break.)

The visual diptych does appear in narrative, occasionally. An iconic example is the split-screen gym scene at the climax of Brian De Palma’s 1976 Carrie. We, the viewers, are given the sick pleasure of staring simultaneously into the face of murderer and victim. The scene would not haunt the imagination without, in one panel, the otherworldly stare of Sissy Spacek’s eyes, and, in the other, the hysteric electrocution of her classmates. De Palma shows not only the violence Carrie doles out as swiftly as playing cards, but the transformative cycle of violence, that the emotional violence shown first toward Carrie afterward transforms her into a machine for generating violence. It’s one of the most satisfying (if I may call it that) moments of gratuitous violence in film—all thanks to the diptych.

But this is still visual diptych, and not what I mean by narrative diptych. Narrative diptychs structure the telling in two separate parts.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s 2004 film Tropical Malady uses exactly this structure: two stories divided evenly down the middle, each a dream of the other. The first shows the quiet romance between two Thai men, Keng (Banlop Lomnoi) and Tong (Sakda Kaewbuadee). The development of their relationship is sexless and sweet—borderline saccharine—with almost no obstacles except, perhaps, Tong’s mild resistance to Keng. Where’s the drama? Around the middle of the movie, the two men are riding a motorcycle and pull off the rode to pee. Keng takes Tong’s hand and smells it, and, surprisingly, Tong drops his inhibitions and does the same to Keng, sniffing and licking the back of his hand like an animal. Without a word, he turns and walks into the darkness.

Then begins the second part, nearly divorced from the first, about a Thai soldier (played by Lomnoi) who investigates the disappearance of a villager and the mysterious slaughter of several cows. A rumor spreads that a shaman in the form of a ghost tiger—played by Kaewbuadee from the first half—haunts the surrounding jungle. (Is this even the same film?) The remaining hour follows Keng’s solo journey through the jungle. He encounters the tiger ghost who taunts him in a kind of poetic take on the Blair Witch Project, and Keng spirals into a frenzy. A nearby spirit tells Keng that the tiger is “starving and lonesome. I see you are his prey and his companion. He can smell you from mountains away… Kill him to free him from the ghost world. Or let him devour you and enter his world.” The second half is tense and brutal, bloody and full of anguish.

It’s tempting to read this second half as a simple metaphor: Keng and Tong’s relationship is like a tiger and his prey. It’s tempting, but I think the equal weight—and time—allotted to both stories invalidates this reading. We tend to see metaphor as merely commentary on the master narrative. It is tinsel on the tree, a sparkling word more about the glory of the Lord, but, at its core, redundant. A metaphor is often misunderstood as a riddle to be solved. Solve the riddle, solve the art, shut the casebook. We treat the device as a matching game for toddlers.

The diptych sidesteps this conversation. Neither half acts as master or metaphor. Both tell the primary narrative and serve as commentary. Each narrative dreams the other; it’s unclear which is the “real story.” Should we believe the second half reveals a violent underbelly to the first narrative, so sweet on its surface? Or does the first half reveal an implicit eroticism between the hunter and the hunted? The viewer need not decide.

The final scene of Tropical Malady contains a visual diptych “haunted by a phantom of unity.” The tiger faces the soldier and speaks: “Once I’ve devoured your soul, we are neither animal nor human.” The soldier yields: “I give you my spirit, my flesh, and my memories.” We never see the union, but this coda stands as representative of the whole, two halves trembling for unity.

Lars von Trier’s 2011 Melancholia also uses the diptych to frame his narrative, the story of two sisters, Justine (Kirsten Dunst) and Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg). The first half narrates Justine’s wedding on her family estate. Subject to intense depression, Justine can hardly stand for the reception and drifts in and out of crippling sadness and rash outbursts. She sabotages her own lavish wedding while Claire attempts to calm her and repair the damage. The second half, called “Claire,” is set the next morning, after the wedding guests—and Justine’s new husband—have left. News arrives that a planet named Melancholia is set to collide with Earth. Claire becomes paralyzed with fear. As the end of the world approaches, a severely depressed Justine remains the only calm, rational character and, ultimately, guides Claire to accept the inevitable.

The two parts are almost different genres—hyper-realist drama and cerebral sci-fi—but both work to say more than each individual half could. Though the film is chronological, the diptych takes pressure off the plot. The parts hinge together as an essay on mania and depression in a crisis and could adopt the title of one of Frank O’Hara’s poems, “Meditation in an Emergency.” The diptych denies us the open-and-shut feeling of a good thriller that depends on the suspense of beginning, middle, and end. The diptych leaves the action open for contemplation.

Melancholia actually started as an adaptation of The Maids. Von Trier began the project for Penelope Cruz, who was inspired by the sisters in Genet’s 1947 play. Though the plot evolved and Cruz dropped out, Melancholia carries the diptychal spirit of the original in its structure.

The Maids opens on Solange and Claire (von Trier kept one of the names), two sisters who are maidservants to a young, rich couple referred to only as Master and Mistress. The characters on stage appear to be Claire and Mistress, but after twenty minutes, a timer rings, and we see the maids are merely acting, Solange as Claire, Claire as Solange. They take turns playing Mistress while she’s away, try on her dresses, give each other orders, and revel in a sadomasochistic tension. The erotic, incestual ritual is their only escape from a dismal life with Mistress, whom they both idolize and despise.

Mistress enters briefly, halfway through, and acts as both comic intermission and structural hinge between the antics of the first half and the gravity of the end. As a diptych, the play generates that meditative dialogue singular to the form: the maids desire escape from the prison of self by confining their selves within desire. The Maids splays open and sticks in the mind like a Zen koan, even seventy years later.

I caught the recent Sydney Theatre Company’s production of The Maids last month, hoping for this effect. Cate Blanchett and Isabelle Huppert played the sisters, which should have made this production the definitive one for our time, but oddly, it wasn’t. For one, a new translation had updated the language—“the Alexander McQueen” for “the red dress”—and flattened much of Genet’s fiery invectives into “fuck” and “cunt”—both poor moves, I think, not because they’re unfaithful or crude, but because they take a grand step toward realism. Genet’s play is defiantly theatrical and resists traditional narrative. In order to heighten the performative quality, Genet had intended male actors to play the maids.

It was as if Benedict Andrews had directed a diptych as a triptych. In fact, at one point, Solange and Claire flanked Mistress on either side, forming a straight line, both mouthing her words in silence, both imitating her poses. The effect was revealing: a pure triptych. The central panel held the most weight when it should have merely hinged. That the actresses were filmed, the live footage projected on a screen upstage, added further to the triptych feeling. Andrews had already “solved” the production for us, and we were meant to watch his ideas. We were not implicated.

The narrative diptych figures in a great number of other contemporary works: Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls begins with a surreal luncheon of strong women throughout history and dovetails into a realist family drama; Samuel R. Delany’s book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue explores the destruction of pre-Giuliani porno theaters, first by personal example, second by theoretical manifesto; Alan Ayckbourn’s House and Garden, are two plays stage in adjacent theaters—when the actors leave one play, they enter the other; and even, I hear, though I haven’t seen it for myself, The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby tells the same story from two perspectives, which you can attend in either order. The diptych is alive and well.

Whereas its more visible sister, the binary, a fascist institution, installs a value that erases the other completely, the diptych presents two in tandem and permits viewers to merge them with whatever mental hinge they choose. We live in a time that praises the binary. Male/female, gay/straight, conservative/liberal. At best, our culture acknowledges the tertiary—transsexual, bisexual, centrist—but scoffs at the suggestion that two separate realities could exist simultaneously.

If anything, we are quaternary, not binary, but we can’t deny our inherent duality, the natural symmetry in two eyes, two hands, two sides of our possessed brain.

Let us now praise the diptych, a form for resisting binary, harnessing duality, and evolving it far beyond, into a system of contradiction, absurdity, and meditation.