A man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover through the detours of art those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.—Albert Camus

Let me take this as one of my heart’s first openings:

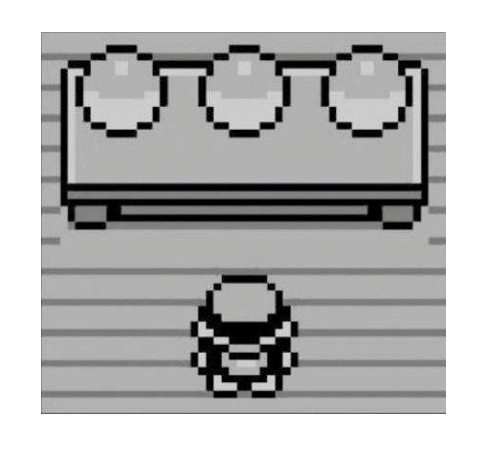

I was eleven when I bought that red cartridge. Now I’m twenty-two, so it was half a lifetime ago that I first encountered the image above. When I stumbled across it the other night, I stared at it for five minutes, suspended. In that internet eternity I realized that the pixels hidden in these Pokéballs have acted as reliable nodes of reference for me in the intervening eleven years.

I was eleven when I bought that red cartridge. Now I’m twenty-two, so it was half a lifetime ago that I first encountered the image above. When I stumbled across it the other night, I stared at it for five minutes, suspended. In that internet eternity I realized that the pixels hidden in these Pokéballs have acted as reliable nodes of reference for me in the intervening eleven years.

Join me, then, in this trek.

A quick primer for the uninitiated: In the game that started it all, we told our forgetful neighbor, Professor Oak, our name, and in exchange he offered us a Pokémon, a companion in adventure, with whom to set out from Pallet Town, where we grew up, and where the loveliest, bright silver music had played ever since we were born. We chose from three different Pokémon. Laid out on a table, they were indistinguishable from each other, until we walked up to each and pressed A, to conjure the image of Bulbasaur, then Charmander, then Squirtle: adorable, indelible creatures and, I realize now, distinctly paradigmatic. When I return to those happy childhood days, I don’t simply remember what it was like to first feel the match-strikes of villainy and vanity and heroism and pathos: rather, I realize that the choice between these starter Pokemon has become for me not simply a measure of affinity to one of three illustrations, but a decision between three archetypal modes of being, modes of aspiration, and orientations toward the past.

Charmander—>Charmeleon—>Charizard

Charmander—>Charmeleon—>Charizard

It bears mentioning—these pixels are so simple, but we aren’t. So if I tell you that Charmander is Norman Mailer, is Jean-Paul Sartre, is that unqueer masculinist with the romantic sweep and the fervent intellect and the uncompromising ambition and the reverence of dominance, well, I certainly don’t mean to say that Charizard thinks himself a world-rending sexual interloper, only that to me those pixels always will be exactly that. They’ll be the alpha-boy of the four of us who picked the lizard with the flaming tail in fourth grade, and they’ll be fire, and they’ll be might, and they’ll be drone strikes and ellipticals and telling it straight. Picking Charmander meant following the toughest route: the first gym leader uses rock-type pokemon, which extinguish fire offhandedly. So it was; Charmander was the hero’s journey, the genius-in-history, the Great Man, and to pick him was to affirm all that. An image, the game’s architecture, and textual ephemera—Charmander learns Rage at level 22—all conspired to construct, for me, young, sensitive boy that I was, an emblem of a particular mode of existence that’s proved useful in making sense of the world ever since.

Poor Squirtle never had a chance. He’s the image-addled mind, the body drained of viscera, pure vassal of celebrity, she who shits out exactly what she consumes, he who tells jokes with a single punchline, chaffy inhumanity, the runoff of social media. She babbles and bubbles float up from her lips: “On Wednesdays we wear pink!” he tweets on Wednesday, chipper from forever until forever, already dead and still always dying. A body composed of authorless, insipid image macros—Live! Laugh! Love! We know, Squirtle, we know, we know. #STOPKONY; Squirtle waterboards your family as she tells you about the HuffPo article he read a week ago—some say Obama fudged the employment statistics…Squirtle thinks Obama probably didn’t do that. Squirtle hopes he didn’t do that. Squirtle grins, orders a frozen margarita, returns to the hot tub, and continues never to comment on, only to comment of—shaken and shivering, Blastoise taps on his iPhone to update his Facebook status: “parents FINALLY posted bail.”

So give me Bulbasaur; give me bell hooks directing Siddhartha-the-motion-picture, Frank Stanford chanting “the gentle the sweeping the cunt of the soul,” and Fernando Pessoa whispering it right back. I choose you Joan Armatrading singing lullabies to Joan of Arc, a full moment wonderfully stoned, a womb and a crown and an archer in that laser-filled, utopian jungle of Paul Simon’s Graceland. Violent surrender and potent non-violence, always-becoming the always-already, the easiest path through the game, the hardest choice to make, some impossible synthesis of the subaltern and the princess, the minor history and the coelacanth, the immortal jellyfish, the Amazon river, the dominance of the leaf. We team up to become the A-minus student, the generous pothead, the fierce galactic mother, emerging from and returning to the slipstream of dreams, in another time, in another place. Van Morrison and Venusaur, astral cousins photosynthesizing. One way of many.

I picked Bulbasaur, and it made a difference, or it’s become one from the vantage of the present. I’m incredibly happy for it, haughty for it, whatever what have you. It’s a badge I’ll wear that few will see. With it I allow myself extravagance. So that tiny image resonates. Three thousand pixels or so, each with its own gradient, and yet I can tease from it much of my life.

Easy enough to move on now, but there’s another part of the game I’d like to revisit, which undermines all of this, hacking away clutter to clear room for finer thoughts. Pokémon’s cardinal Kristevan abject—the object which, precisely in its being “cast out” of a symbolic order, lends that order its structuring identity—is the best machete we’ve got:

MissingNo. is Pokemon’s manchild-in-the-basement, the guts of the game’s logic splayed for the oracle to read, the voice shouting for help that disappears when you turn your head in its direction. MissingNo. has no origin story—no one knows who found it, and popular opinion says it is a true glitch, unmeant to exist. If it is a hoax, a long-con marketing scheme, well, I celebrate its genius. Encountering MissingNo. requires a laughably superstitious ritual—talk to the old man near your home, let him lecture you on how to catch a pokémon (you’ve long since learned), then fly to one of the last zones of the game. Enter the water there, surfing on the back of one of your pokémon, and move about until the battle music begins and a staticy tetris block drifts across your screen.

Catch it and things get weird. You’ve suddenly got 99 of the sixth item in your inventory; various animations glitch and freeze; the music cuts in and out, the screen goes black, the Gameboy feels heavy and terrible. Put MissingNo. in storage and it turns into Rhydon; give it any experience points at all and it reaches level 100; one of its types is “Bird,” a vestige of early localization, when the Flying-type was less gerundive. Any one of these things would feel like a logical progression—fuck with the game and it fucks with you back. That’s how code should work; that’s how reality should work! What’s so unnerving about MissingNo. is that its presence alerts the gamer to a vast network beneath the world, a hidden set of pointers and digits stored with a complexly cyphered relationship to the cohesive presentation of the game. Simply walk the steps necessary and you’ve conjured a ghostlier world, one that won’t be debased to the logic its creators meant for it to follow.

There’s an explanation to the madness, of course, and its structure is familiar: do something macro-level that screws with the micro and watch as the world goes batty. Gain mastery and watch as the world conforms to your will. Magick. Normally when you throw a Pokéball, the battle text reads “[yourname] used POKé BALL!” When the old man teaches you to catch Pokémon, it says “OLD MAN” instead. In order to remember your name when ‘OLD MAN’ rewrites it, the coders of the game stored your name’s letters (in the form of hexadecimal values) in the slots that become, when the player enters a place with wild Pokémon, the values of the Pokémon that can be found in that particular place. In the small patch of water off Cinnabar Island, those values were never initiated, so the values are those from your name—and since there were only 151 Pokémon, 105 hexadecimal slots are filled by MissingNo., or ’Missing Number.’ From that first displacement cascade the rest.

What’s so marvelous about this labyrinthine discovery is that it ruins almost nothing. Legends say encounters with MissingNo. can rewrite your saved data, erase entire files, combust your cartridge, but they’re unfounded. Certainly understandable, though. The glitch feels too conspiratorial, too Illuminati-wrought not to be dangerous, and surely we must be punished for these 99 Rare Candies, each an effortless levelup. But no; the world persists—shredded, bleeding, but alive, and we’re left reeling, dimly aware that whatever logic exists bears only a Gothic resemblance to our own.

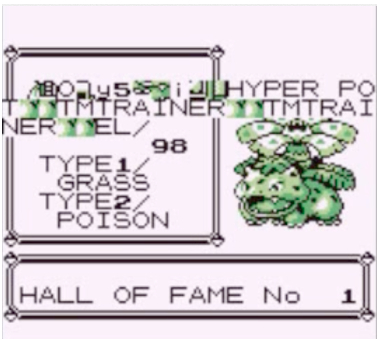

Pokémon ends with the Elite Four. After defeating them once you can fight them as many times as you’d like. Each Pokémon that’s in your party during a run through enters the Hall of Fame, its data logged and glorified. The uncanny scrambling of these records is one of the only irreversible effects of catching MissingNo. No traditional measure can last once the willfully forgotten of the world have been remembered; no compact can resurrect old hierarchies. So the abject MissingNo.—mistake, code-defiler, unorchestrated symphony—scuttles the crowning of my Venusaur, makes mockery of my friend’s Charizard, and humiliates another’s Blastoise. And so it always will.