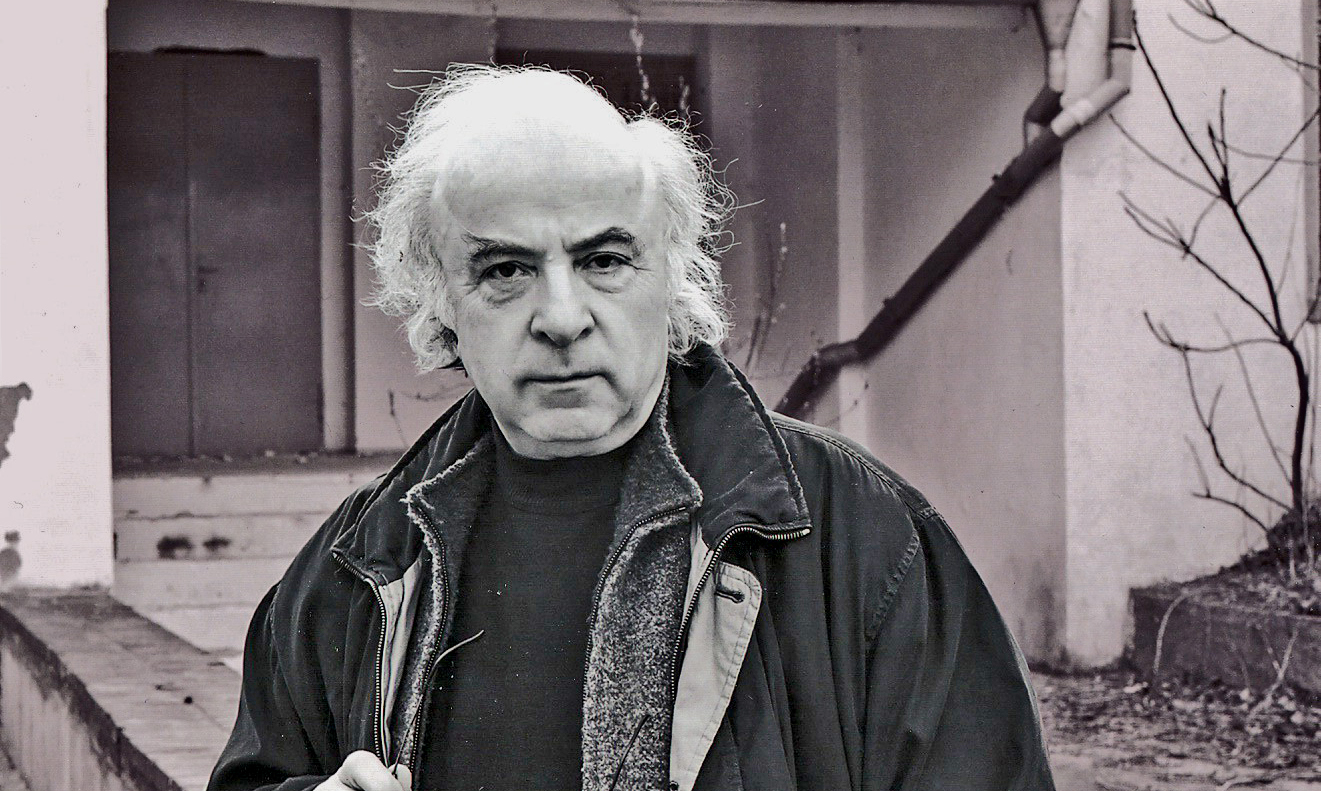

Original photo by Isolde Ohlbaum.

Original photo by Isolde Ohlbaum.

Norman Manea was born in 1936 in the Romanian province of Bukovina. As a child, he was deported with his parents to a concentration camp in Transnistria, the area of Ukraine that Hitler handed over to Romanian governance during WWII. After the war, Manea continued to confront anti-Semitism under Romania’s fierce communist dictatorship, particularly from the 1960s onward, when he began publishing writings critical of the government and refused to comply with censors. Eventually, government persecution and the receipt of a DAAD grant from Germany led to Manea’s emigration in 1986, and in 1988, he came to the U.S. on a Fulbright Scholarship before becoming a professor and writer in residence at Bard College.

His novels, short stories, and essays typically draw from his experiences with totalitarianism and his later life as a writer in exile living in the United States. His works have been translated into more than twenty languages and in recent years, international critics have considered him a highly plausible candidate for the Nobel Prize. Yale University Press recently reissued his novelistic memoir The Hooligan’s Return (originally published in 2003 in the U.S.) as well as his novel The Lair. The Captives, Manea’s first novel published in Romania, is forthcoming from New Directions.

I sat down with Norman in the living room of the apartment he shares with his wife Cella on the Upper West side of Manhattan during one of their brief visits to the city—they spend most of their time in upstate New York. Upon hearing that I am the first American-born in a small family of Soviet-Jewish immigrants, Norman was eager to converse with me in basic Russian and to hear about my own struggles to define identity and homeland—issues that have formed the cornerstones of Manea’s writings and upon which he is often asked to comment. He was gracious and thoughtful throughout our exchange, speaking English with a rather strong Romanian accent and undercutting any self-seriousness with a healthy dose of ironic, sometimes self-deprecating, humor. At the end of our interview, I asked how he thought one might escape the constraints of social identity. Manea replied that there is no one recipe for everyone, and that, “in the end, what matters is the intensity with which you live loneliness, creativity, love, anger, sorrow, frustration, joy, within the many, ephemeral social identities that we are granted.”

—Elianna Kan

✖

Elianna Kan: In a number of your autobiographical writings, you discuss your earliest encounter with literature, saying you’d “discovered the wonder of the word.” Describe that experience and the impact it had on you.

Norman Manea: I was nine years old. It was April of 1945. My parents and I had come back to Romania after being deported to the concentration camp in Transnistria. It was a time of extraordinary and sudden joy, rediscovering what I call the banality of life, the very basic things: food, clothes, school, especially. We were staying with relatives who hadn’t been deported. They spoiled us because we had come back from hell and nobody could believe that we had survived. This period between 1945 and 1948 was still quite a confusing time in Romania—the Communist Party was not yet in power—but everyone, as is often the case after a disaster, was full of hope, regenerated vitality. There were love affairs, music, dancing, food.

For me, as a child, it was magic. It was a time of intense joy. And it was during that time that I was given my first book of fairytales. Nobody had told me fairytales before. Never. I received this book and I entered into another universe. It was a book by a great Romanian storyteller, semi-folkloric but with wonderful language—language that was not the language of the streets. I was mesmerized and in love. This period after the war and this first encounter with this book remained for me a mythical moment. From that time forward, I became an avid reader and read whatever I could get my hands on.

EK: When you talk about discovering the wonder of words you say about literature that “it was both the illness and the therapy.” What do you mean by that?

NM: I mean that life itself gets put aside a bit by literature. You enter into another world which is not actual reality, it is a different one, a parallel one, and if you start to belong more to that other reality than to the one in which you live, it’s a perfect premise for failure or for becoming a dreamer without any connection to actual reality. So I decided childishly to become an engineer.

EK: To avoid living in that alternate universe?

NM: Yes.

EK: But was there belonging you found in that alternate reality that perhaps was more meaningful?

NM: Well, when you are young, reality itself is meaningful and rewarding because you are young—you have love affairs, you have reading, you have the vitality of that age which is rewarding. But this writerly preoccupation can, at a certain point, become more important than reality itself. I was always split between these two modes of existence and although I practiced engineering for some fourteen years, I still continued to write in my spare time. I had this duplicity, if you will, but it was an enriching one.

EK: When did writing become the all-consuming, full-time focus?

NM: After I published my first book, in the sixties during the “liberalization period” in Romania. My first story was published in ’66 in a small, avant-garde magazine which was banned after five issues. Though I belonged to the Writers’ Union in Romania, I was not the typical, official Socialist writer. My books were not in the frame of the Socialist Realism of the time so I ran into problems with the censors, editors, and so on.

EK: So to what extent did the state censorship effect your relationship to language? When you talk about discovering literature there was something wonderful and transcendent in the language of fairytales, —how could you strive for that in light of state-policing?

NM: It was certainly a negotiation with the official “wooden” language of the papers and with the published books which followed party propaganda. My first novel appeared in 1970, it was called Captives. The title already was unusual and the characters in the book were defeated people, not the winning heroes of great socialist literature or the Hollywood variation, where everything has a happy ending. I faced a lot of objections and problems for refusing to follow the recipe of Socialist literature.

EK: And you resisted tailoring your language.

NM: Correct. My language tried to be faithful to a closed society, rather than an open one. The language was coded, sometimes quite obscurely, and differed greatly from the language of newspapers or party slogans. The characters were usually marginalized—people who were foreigners in their own land.

EK: And you trusted that this “closed universe,” as you call it, would resonate with the reader?

NM: Yes, it was an implicit connection with the virtual reader. The newspapers were as they were, but from a literary book, the reader expected that he or she would find something beneath the surface and in that time and place had become well trained to read between the lines. These books would never succeed commercially if we tried to publish them here, today, because they are narrated in a language that is self-sufficient, coded—not how you would write in an open society. It’s a different kind of literature and a great deal of it died with the system.

EK: For better and for worse?

NM: For better and for worse. I don’t know exactly. What I do know, is that I refused to compromise with the system and I was obsessed with preventing my work from being manipulated for their propaganda. Even stories about the Holocaust could have been promoted as anti-fascist stories, which they were in a way, but I didn’t want them to be taken only as such. I remember I had a reading in Berlin in the ‘80s and a man in the audience, asked me: ‘Sir, I read your book, I read the stories, you didn’t say who the oppressors were nor who are the people who are suffering.’ And I said, ‘No, I didn’t.’ It was important to me that a Vietnamese reader reading a story about a young boy who is in a camp, can recognize himself, without me saying: the boy is a Jew, the oppressor is a Romanian, or a Nazi, and so on. I wanted to have a more universal approach.

EK: Even though your relationship to these experiences was very particular to your own biography.

NM: Absolutely. But in your own specific biography you always find something universal.

EK: When you emigrated to Germany and then to the U.S., you continued writing in Romanian. How did your relationship to the same language but now utilized in an “open society,” as you call it, change? Was there a re-negotiation with your own language? Or did you continue with a similar relationship just in a new context, now yourself living physically in an open society?

NM: It’s a very good question and you know good questions are not easy to answer. I left very late and I was handicapped, I came without knowing any English. You can imagine, with my exotic Romanian, I was practically a deaf mute. So of course, I negotiated with the language and also with the literary culture of the new place.

EK: How do you mean?

NM: I began first by trying to write essays. I thought this should be easier because the essay, unlike narrative fiction, follows a more or less logical framework. But I quickly realized that here essays are written differently than how I had been accustomed to writing essays.

EK: In what way?

NM: In the way that in Romanian literature and probably also in the Latin-speaking part of the world—French, Italian, Spanish—you have a sort of implicit communication with the reader. You assume that he or she knows more or less what you know and thus, you can start the essay from an implicit point of view. This is not the way of communicating here. Here, every piece in the newspaper declares in the first sentence what the piece is about. For example, even if we’ve been speaking about the mourning of Nelson Mandela for a week now, every time his name is mentioned, you must specify that he was the president of South Africa, that he was ninety-five years old, and so on. Everything is tailored to the most common denominator. If you buy a can here, there will be instructions for the most stupid guy on how to open a can. This was not the way of communicating there. Here, because it’s a popular kind of, trivial democracy, and the average guy on the street is, in a way, the center of society, in order to sell these cans, or your newspapers for that matter, you need to communicate directly to him. So, this was the first kind of linguistic test here—

EK: Adjusting to the mode of expression.

NM: The mode of expression, yes. The next test was figuring out how to avoid clichés when writing about the topics about which I was writing—Jewishness, concentration camps, all of these things.

EK: Or you end up just serving the label that has been conveniently assigned to you.

NM: Exactly. Here and there. Here you have to accommodate the economic censor, the editor, and so on. There, you had to accommodate the party and the rules of canonical socialist literature.

EK: So these essays you wrote in English or in Romanian?

NM: I write almost exclusively in Romanian. As I said, I came late. In your native language, you grow with the language—from childhood to maturity and you harbor within yourself the language of all these ages which changes over time. Here, I learned the language of daily living but I don’t know the language of all ages. I was not here as a child, I was not here as an adolescent, and I didn’t study literature here.

EK: You mentioned trying to evade the clichés that accompany identity labels—which we love, here, I think. At one point in your memoir, you discuss your annoyance at being included in a 1970s anthology entitled Jewish Writers in Romanian. Don’t you think that “writer in exile” or “exile writing” has become the new, all consuming, ubiquitous identity?

NM: Absolutely. It’s a new big chapter in contemporary literature because of the social-political situation of the planet. Migration is now accelerated. We live in a more global society, although, exile is actually an old story—from the Bible and Greek mythology—it’s not something new, but the amount of exiles and the acuteness of the situation is on another level. But I’m skeptical about collective identity. What is identity in the end? I’m more interested in Gertrude Stein’s discussion of this problem of identity when she distinguishes between entity and identity; entity being what remains when you are alone in a room: in that moment of solitude, the essence of yourself, which is something, at least a bit different than the collective identity, your individuality, prevails. In the end, you are an individual.

EK: So would you say when you’re writing, ideally your literature transcends the identity politics and gets to that person who is alone in the room with the door closed?

NM: More or less. You cannot avoid taking into account the environment that forms and deforms the individual. Unfortunately, I had to face some collective tragedies that became individual tragedies.

EK: What is it, though, when you mention being frustrated at being called a Jewish writer who writes in Romanian and then you say, now thirty or forty years later, you wonder if they weren’t right by calling you that? How did your perspective evolve?

NM: When I was sent to the camps, I was five years old. I was not a Jew. I was nothing. I was a little boy. What did I know how Jewish I was or if I was Jewish. I came back very eager to become like all the other people. So as to no longer belong to this “chosen people” or this damned diabolical people. This explains why I became a very young communist: the ideology, the utopia of everyone being equal and anticipating a great collective future was a wonderful fairytale for a young boy of nine, ten, fourteen. Thankfully I woke up in time—at fifteen, I think. When I came to America, I saw for the first time in a bookstore, or a library, that writers were divided—women writers, black writers, Jewish writers, gay, lesbian, all these wonderful things, but in groups. In my opinion, a writer is defined by language. So these are all American writers. Whatever they choose as their topic is their problem, it’s their choice, it’s their…

EK: It’s their illness.

NM: Illness or whatever, you shouldn’t divide them in this way. But I understood with time that this is what I am. I am a Jew. I may negate it. I may dislike it. But that’s it—because despite all my efforts to try to be different, to be, as I said, more universal, I am still also something quite specific, whether I like it or not.

EK: In one of the essays in The Fifth Impossibility, you discuss your ambivalence towards a quote by George Steiner in which he says that “truth is homeless.”

NM: Yes.

EK: Do you think that’s an illusion?

NM: I don’t think that it is an illusion but it’s not the total truth. It’s certainly a part of the truth. And there are other parts, which we cannot ignore. I mean if we want we may ignore them, but…

EK: But it’s still a choice.

NM: It’s still a choice.

EK: In reaction to something else.

NM: I think so. I think so.

EK: On the theme of homelessness, when you read your work in translation now, after having lived in America for more than twenty years, is it still as revelatory an experience as it was initially? What is it like being a writer in translation?

NM: It is not a comfortable situation being translated in the country in which you live, although it’s not necessarily your homeland, it’s only a domicile and, as you know, I once wrote that America is the best hotel.

EK: What do you mean by that?

NM: I didn’t say that it’s the best country. It’s the best …

EK: It’s the best hotel?

NM: Hotel. Yes.

EK: Why?

NM: What is a hotel? A hotel is where you come in, you have a place for which you pay, everything functions, nobody asks who you are or what you want. You have an ID, you give the ID, you come, you go, and that’s it. It’s a domicile and it’s a temporary one because we are temporary here on this Earth. And here, to the constitution at least—although the reality is of course much more complicated—you are a human being, and the only thing that is asked of you is to respect the constitution. Which is fine by me, I respect the constitution. I am not asked to be a Catholic or a born American or to be an anti-Semite, but I can be, if I want. What was the question?

EK: Reading your work in English translation while living here in the U.S.

NM: In the beginning it was a nightmare. There were almost no translators here from Romania. My first book of stories, which was published by Grove, had a number of translators but the translation ended up being very bad. The book had already been published in Italian and French, so with the help of those editions, my editor and I rewrote the English translation. Quite a laborious process for one book, as you can imagine. Now, I’m more used to the language and there are translators here from a younger generation who are more or less bilingual, so it’s easier. But still, in any language, you’re not the same. You are never exactly the same because the languages are not the same and there are words and even meanings, which are so specific that cannot be transferred—transported—exactly from one language to another.

EK: Nabokov wrote about a variety of untranslatable Russian words—tosca being one of them. Do you have any words in Romanian that, to your frustration, you can’t quite translate the nuances of into English?

NM: Nabokov, whom I like very much, has a poem to which I can relate that he dedicates to the Russian language and in which he effectively says to the language: free me, let me go, don’t keep me in this cell. But Nabokov was a very special case. At sixteen he was already abroad, he was from a very wealthy family and from an early age he had teachers of German, French, and English even before he learned Russian. So he is usually given as an example of a writer who switched languages but he’s really not the best example.

In any event, one word in Romanian which is considered untranslatable is dor. It means, more or less, longing. It’s one word, with many layers in itself. And if you translate it into English—longing—it’s not exactly the same. Romanian has the advantage of not being such a framed, established language as classical European languages: English, French, German. Instead, it has voids and hollow spaces with which the writer can play.

EK: When you read contemporary Romanian writers, do you have an affinity for them or does the language they use feel entirely different from the language you took with you when you left?

NM: Of course the new generation of writers writes a bit differently. Language is dynamic. In twenty-five years, a lot of neologisms and new words have entered Romanian from America, from the TV, from…you heard about this ‘selfie’? In the British dictionary?

EK: Yes!

NM: Which is something new, it didn’t exist yesterday. But you can’t control changes in language. When I went back to Romania, I was watching television and I found the language that is used today extremely trivial. A mixture of Americanisms and the most vulgar, low kind of American language.

EK: And you think it has invaded the literary—

NM: It did, but again—I prefer to speak about the individual, not about the collective. And so there will always be, in Romania and elsewhere, writers who will find an original way of expressing themselves, of giving themselves to the reader.

EK: So you’re optimistic.

NM: Not at all—

EK: Not at all.

NM: I’m pessimistic, by nature, and I consider this the very best solution for life, because you are never disappointed if you’re a pessimist. If you’re an optimist, you are disappointed at every moment.

EK: At the end of one your essays, you say that you “don’t believe with Dostoevsky that beauty can save our world, but we may hope that it can play a role in consoling and redeeming our loneliness.” Do you still believe that?

NM: I do, I don’t see—to be very honest—I don’t see anything that can save our world. But to console us, literature may have its place.

EK: Do you think that place is changing?

NM: It is. Certainly. You have this little device [points to iPhone] and your colleagues also have it, and this little device will become smaller and smaller. This is certainly another world! The speed of communication is different, the influx of information is immense, but I fear real, deep human communication is diminished in this aggression of information. It’s overwhelming, you can’t possibly respond to all of it. Individual communication inherently has smaller place in this huge deluge. At least this is how I see it. Again, for better or for worse, I know that your generation is already used to it—

EK: It doesn’t mean that our need or our desire for prolonged, meaningful, concerted thought and communication is different…

NM: No, that’s not what I’m saying. I am absolutely convinced that even if your problems are a bit different from ours, you are still very, very human, and your needs are more or less the same, but you are formed—and deformed—by another time and it’s changing very rapidly, as we speak.

EK: And yet you continue to write.

NM: What can I do?

EK: Why?

NM: It’s a consolation. [pause] A disease and a therapy, at the same time. But also a consolation. You write in order to redeem yourself partially from the chaos which is around you, you’re trying to find something, meaning, somewhere. Or to invent one, if you don’t find it—and this is what produces art generally: this need of the individual to search for something which is beyond their reality, even if it is sometimes hidden within that reality.

✖