This story has been drawn from the August issue of the American Reader, available here and in independent bookstores and Barnes & Nobles nationwide.

✖

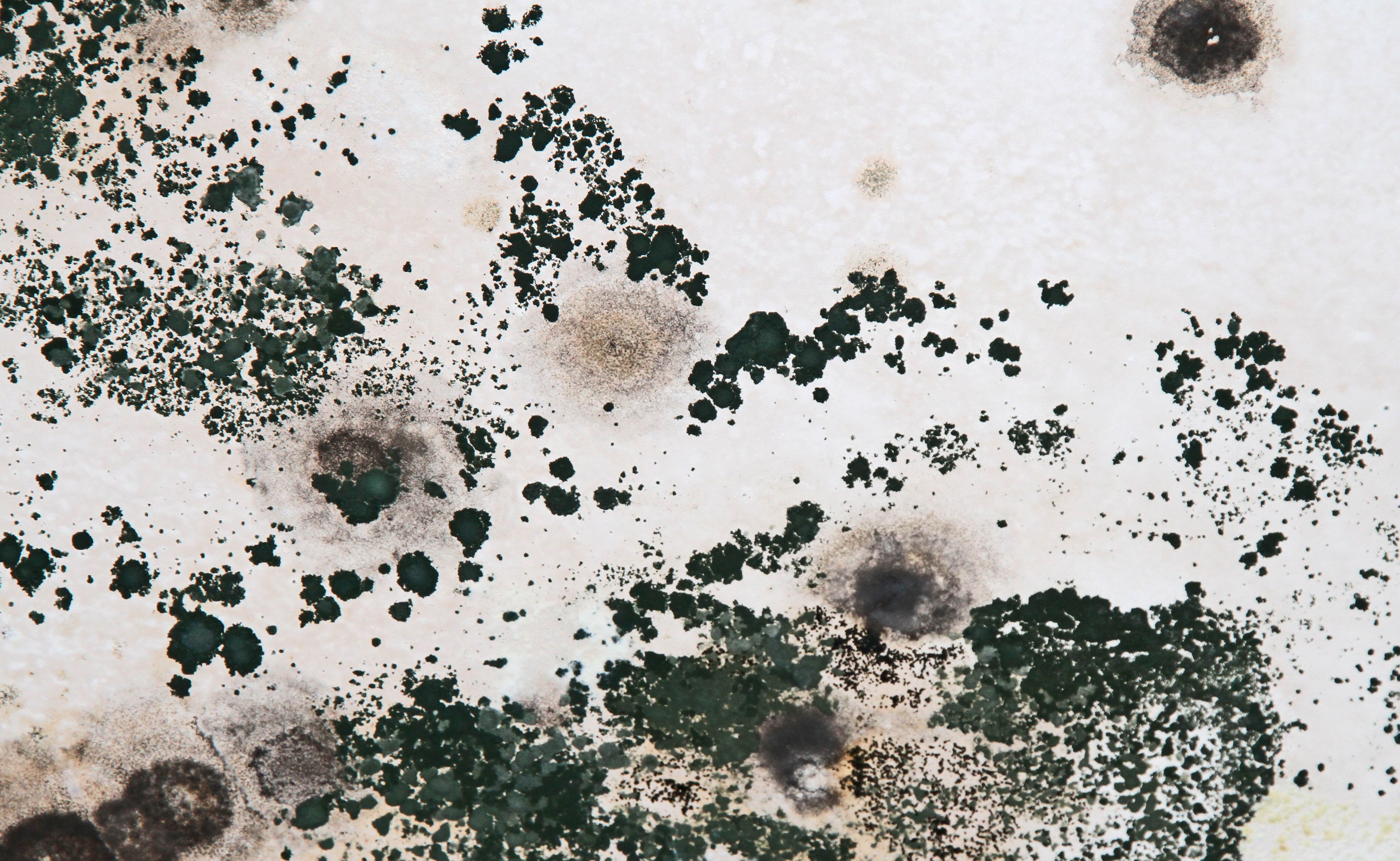

My wife found our late child’s markings in the mold that lined the far barn. It seemed he’d cut them with his teeth—same way he’d ruined the woodwork in his crib, wrecked my dresser—symbols gnawed into the color of the growth. This time, though, instead of jabber, the boy had made his name, the same as mine, and then there under, in a smaller script, his date of birth and date he’d died.

We’d found the child two weeks prior laying facedown in the white brush of the front yard. Flies caked his face and arms though there were no open wounds to feed on. I brushed his cheeks clean with my hand, to see the stretch marks there where his skin had been loosened from his face.

The child at first had looked exactly like me and his mother both at once, though as the months came on, quickly, he began to look like anyone that I could think of. They bled together in him in my mind, all faces, all ideas.

I’d always felt my boy would live forever. He seemed strung with a different make of vein. I’d once watched him bang his head hard on a lathe out in my workshop in the midst of chasing moths, and instead of crying, whining for mother, his body shook with hiccupping elation, a brook of blood tracing his cheek down to his diapers. Only months alive he’d had large canines. When I’d let him, in his mother’s absence, he liked pounding nails with the tiny hammer I’d provided. I’d caught him more than once chewing on hunks of dirt or even glass, which he’d swallow grinning as I tried to make him spit. How he could stare straight into a blowtorch, beg for me to lay the hot blue light in his hands and sit like that for as long as I could stand to hold it with him. Three years old and already beyond anything I had imagined in a son.

Three years old, already gone.

The other markings he’d made around the house and fields in prior months had never looked like language, or even sense. Sometimes there’d be a picture in the mess, like for instance, the shape of a man’s face gouged in on the top side of the coffee table, though really it was hard to know if the shaping was intentional. You could make what you wanted of almost anything.

This most recent strain of mold was blue as sky had been once. Over the recent months it’d shifted through hues I by now could not remember but as mass. The stuff had quickly encroached on no small part of our farm, knitting and blooming on land where nothing else seemed to want to come up. The whole west field was wrecked for acres overgrown, the mold climbing up on whatever it could cling to. It suffered through the soil, the acidic froth all underneath me itching thicker every minute. For months, I’d been out sunrise to sundown prodding, taking soil samples, asking, asking, in the name of God what’d gone wrong. There’d been no abnormal rain or warmth that season, no different raising, but by now there was hardly anything to feed on. Soon we might have to give the land back, and then where we would head? Even in the mold, this was our home now.

I looked again at my son’s alleged words, how where beneath the mold scraped free the wood of the barn beneath was mealy, loose. Could all that scratching really say what it appeared to? Was that my son’s name or just a scrawl, a bunch of dots? There seemed no way our baby could have waddled all the way out here past the empty pasture through all the soft mud, in some spots deeper than he was tall.

Either way, my wife demanded we cut the panel down and bring the inscribed panel into the house with us. This she needed, she said. This was ours now. She wanted to keep near and dear the only text her child would ever write. The way she traced her thumb over the first letter of the surname we three in the wet sunlight shared made me shrink back into my skin. She had the saw my grandfather had used to build the house we lived in already at the ready.

I told her no. I said it’d fuck up the whole barn. You can’t just cut a chunk out of a barn like that, I said, because you want to. If she wanted to remember she could cross the field and look and there it was and it would be.

Pauline didn’t answer. She had her thumb now against the jagged digits of the death year, as if she could rub away its meaning.

I took her by the hand.

I led her back where we could sit down on the porch but she went on inside. She sat stiff in her tweed chair in the sunroom and refused to speak or come cook dinner. She didn’t come when I turned in. I faced the window for once, having no one there to breathe on.

✖

The same day my son had come out of his mother, in the blood robes, I’d lost seven cattle in a wave; each of them fainted on the lawn, the skin in their cow faces having darkened, the capillaries popping and hemorrhaging. By the end of that first week with him inside the house, nuzzled and sucking at her chest, the rest of our whole herd had hit the dust—the wormy meat inside them not clean enough to eat still.

By the second week, the hens and horses, too, had become puddles. Skin and feathers flying in the light. Eggs ejected black and gold air, leaking into the softening ground.

On the day of the child’s first birthday, I’d found the first spores of mold crept onto our estate, rendering in small buds around our bedroom window. The wind chimes on this same evening discontinued making song, and instead would eject a slurring hollow bonking, like bone on flesh, which jarred my teeth so hard I couldn’t eat.

The grass around the house wilted to patterns I would stand in hot sun and try to read, while the child made sound pour from his mouth and scratched and chewed.

Before all this, counting backwards, I could recall the day we’d had the sex that made the baby. A kind of burning in my veins when the sperm left me, a feeling following like I’d passed a stone or something sharp. Pauline’s long moaning continued well after our thrusts had stopped, and regularly thereafter through the months of incubation, as the seed inside her made her sick. First with nausea and bending feelings, a sense of something coloring her in, then with behaviors that didn’t fit the her I’d known forever. She’d eat glass and bits of pillows, clumps of hard air. She’d eat the mold out of the bathtub and the cupboards. New colors appeared showing through her skin like tiny bruises as she grew.

And yet for all these things I’d loved the child. I’d called him hers and she mine.

✖

I woke sometime choking in the darkness, throat cords scratching, hot, something fuzzy looming in the air around my face. Sitting up I saw the sheath of molded barn boards propped up half-a-foot thick against the butt end of our bed. Their stink suffused the room so damp and rich it hurt my thinking.

I got up and fell over something on the floor. My wife, nuzzled up there on the carpet, drooling. She had the peat all over her face. I shook her shoulders, spat her name. I couldn’t keep myself from shouting how she’d ruined the goddamned barn, the way she ruined anything she had a hand in, and always had and always would. I didn’t mean a word of it, but I felt it, and I could not keep it from coming out.

My wife beamed back at me drunken. She had the mold all in her teeth too. I got up and stood over and shook her, my own arms also shaking, until waking up, she kicked away. She scuttled from me to hide behind the barn hunk, peering at me like a larger, mottled child, inhaling terrified. She watched me like that until I left to go stand out in the yard and look at nothing.

The house stayed still for days thereafter. It was harder to breathe or to get food down. The house in whole seemed smaller than any room. When crossing paths on odd ways going wherever, my wife and would keep our eyes on straight ahead, each of us trying not to see the other. I felt her hate me in my brain, a foamy emotional replacement for what had once been love for child. If Pauline was embarrassed by what she’d done against my wishes, she didn’t show it, though at some point the boards moved from the bedroom to the den, where when he’d been alive she’d like to entertain the child through early evenings, the two of them babbling back and forth in no clear tongue. Now she locked the den door to keep me from coming in and doing whatever else she’d thought I’d do. Even passing by there made my chest hurt, something hot and large there newly affixed in my flesh.

Though the smell of mold suffused the entire indoors early on, by the second day I’d grown unaware about it, even maybe fond of how the thickness dragged at my lungs. I’d quit smoking only days before the child came out to share our air, though I could feel the years of old smoke still in there swarming.

In the house I’d hear doors open and doors close. There were large items dragged around along the wood above me or below me. Sometimes the sound of Pauline singing filled in muffled from far-off rooms, though I could not understand the words, or when she’d ever sounded like that. Her voice seemed stretched beyond its limits, thinner, higher.

Many nights I’d wake abruptly and not be able to open my eyes. I couldn’t move my arms or say a word straight. My blood would seem to shake, and then the bed would shake too, and suck me to it—fingers combing through my hair—a sound like something frying—heads of tiny needles breaking through my scalp—though when I could see again the air was wider somehow, newly open, as if something slow and huge had come and gone.

Often in the house I could not find that woman, my wife, whatever that word meant to us now, though I could hear her through the walls, moving as I moved too, as if at odds, so that when I moved to see again, she’d be gone. I’d hear her in the library, where books had fattened, the pages nearly see-through with greasy film, and come to find the room there empty, surrounded soundless.

The den door for long nights would be locked. I didn’t remember it even ever having had a keyhole.

✖

In the land around the house for days thereafter I sludged morning to evening, searching for strips of clumps where something cleanly still remained. For miles the only color was the molding, punched in fists all through the rise. Every day it seemed to spread on farther. The peat would cling against my skin as if knitting into it. I found it hard to lift my feet and walk. In some patches my legs sunk down knee-deep, something crawling low around my thighs. I kept forgetting which direction I’d come in from, where I was headed and for what, the only familiar marking on any semblance of horizon now the shape of lowly structures I or men I’d come from had built up with our own hands.

I say I was looking for a clean place, but really I knew we were already beyond that. It had been so long this way already and I had searched forever and tried the chemicals and seed. I’d waited for the rain and for the hours to make our fields right. What I was after on the earth was any other shape of word; a scratching or a tracing or a making of any sort, in my child’s hand or some other’s, that would prove my wife was not insane, that our lives were being written out before us, and if so, hopefully, there was something more. A kind of word that could in some way make of with what we’d been increasingly surrounded less true, or more true; in any way different from what it was as it was now.

The longer I went the more my breathing grew difficult with all the color in its folds.

The less I found the more I wanted to find any kind of place like that before, such as how somewhere out here once we’d had a garden, planted in the summer well before the child, before the mold had grown from something tracing in our pipes to cover all. For so long the colors had flourished, waking in its wall, a nearly humming room hid in the outside where bees and bugs would come to fry. It’d taken longer at least for this section to fall into the far-resounding ruin. The bulbs with names I could not recall had grown to chest height, the grass bright green and clean enough to eat, before sometime too the itch had gotten in it also, incorporated its body into the larger, darker body. Still, it was somewhere, of a time I could recall. I walked and walked along the land until I felt sure I must have touched it. I walked until I could feel precisely where my body needed water.

From a distance the barn itself looked like one enormous balled-up sweater frayed under the light.

From a distance the house appeared to not be there.

My wife appeared then, running forward at me. Her body grew out of the blur, recognizable as human only as it came near enough to render. She hefted something bigger than her body in her arms, an oblong object made so white it almost pulsed. As she came closer, I recognized our rocking chair, a relic passed down from her mother’s mother, its wooden arms wide as my own.

At first, as she came running, I thought she meant to hit me in the skull—and I did not shy, I leaned into the coming, something in me there saying hello—though when she arrived, thrust among such breathing, she simply sat the chair upside-down there on the ruined soil. She stood and stared, already sop-soaked. Her face was flushed bright white.

“Look,” she said.

I looked.

This was a chair her mother as a young girl had been rocked in and therein rocked in return had rocked Pauline, until in her years the mother passed and so in passing passed the chair on and in our own time she and I had taken turns, singing our son to sleep in the evenings in our own voices, voices given for the same.

My wife pulled my head down to look closer.

In thick dust trapped on the underside of the seat’s curved wood, slit with small incisions along the edge, in a hand that seemed at least in form to match the hand that scratched the barn’s mold, was another name and set of dates:

PAULINE DURHAM

August 13 1930 – August 14 1960

“Two weeks,” Pauline said. “That’s in two weeks.” Her voice was flatter than the land. She moved me aside a little and brought her head down near the numbers, inhaled to say something she didn’t say.

I felt a coldness rise inside me. I heard me speaking. There were colors on the sky. I reached to turn the chair to reface upright, to rip it from her, but Pauline grabbed me by my wrists. Her nails stuck in my skin, cutting blood up to the surface and running briefly down my arm. Her eyes were funny, lit, like someone else’s.

She touched the chair hard on its seat.

“I hope it’s right,” she said, smiling. “I really hope so. So there’s a reason. Something in his head. Something he knew. Beyond.” She went on looking at me as if waiting to be crowned.

I tried to say how the fact alone that he had been and was our son was all enough; that he’d live without end in our thoughts or minds or other as a thing we brought into the world, if briefly—though the words felt wrong inside my mouth. Like chewing something that wasn’t food. Overhead the air was turning old. Pauline continued staring at me blankly for some minutes before she turned in one sharp motion and started running back through all the mud toward the house. I watched her go until I heard an old low wind inside me change direction.

“You did it, didn’t you?” I shouted, in a strange voice. “Made those dates, saying you’d die.” My wife stopped but didn’t look back. I spoke again, holding the rocker up with both hands near the sky. “And maybe you made the ones out on the barn too? That would make sense. He’s a baby. Was a baby. Is. Pauline? Honey? You made those markings and these markings. I can feel it. You made him say this. Did you not?”

The longer my wife kept her back to me saying nothing, no longer moving, the older I felt, the more uncentered and obese, like what I was and always had been was growing out around me.

Her long straight black hair shined under the daylight.

✖

Pauline slept through coming afternoons, there with the mold wall in the rocker with her chin against her neck. She stopped locking the den, no longer concerned about what I might do, or anybody else. The wall itself held some low tone about it, it seemed, as if the sun it had drank into it held within the threads. My wife stopped responding when I addressed her, as if she’d rather the wall be the one to speak.

In other modes she spent long hours at the kitchen table with a calendar, shading in the squares of numbered days to come. She sang to herself in little hymns without a center, as she had when full of child.

I slept mostly in fidgets, imagining the soil waking up around our home. Dark dirt crawled in over the front porch in my mind, mulching the wood up to our rooftop with us still huddled inside. The rising stench of mold curdled in colors, working its way far down my linings. I coughed up chunks. I felt older every second, twisting in me, thought begetting thought. I couldn’t stop imagining, against my better comprehension, how perhaps our son had really known, how somewhere in the house now there were other words we’d not yet found, sentences designed to name the future, a set of dates meant to be mine, the earth’s. Where once the silence had seemed at least steady, now there was nothing not obscured, on the verge of turning over. And though as I combed the walls and crevices in sleepless darkness and found nothing, I still felt them hidden somewhere I’d yet to touch, the incessant surfaces all throughout our house and well beyond it laced alive with hidden premonition waiting to become.

✖

The next time I went out into the kitchen there was a dress draped across the table where for years my wife and I had eaten as a couple, side by side. Pauline stood above it with her face made up and long white gloves on.

“This is which one I want to be put under in,” she said somewhat toward me. She ran her fingers on embroidering. It was a yellow, ruffled thing, what a little girl would wear, and a tight fit for her current outline. Her voice had taken on a kind of calm I thought she had forgotten. She looked against my eyes. “I know this isn’t easy for you,” she said. “I’m sorry.” She crossed the room and squeezed my fingers in her fists and smiled. “I will truly miss you. You’ve been…my husband.”

I dropped her hands and let them hang.

“You’re disturbed,” I said, “Or dumb, too. Forget about it. Get the idea out of your skull.”

Pauline’s face became a mask of pity. She moved for me with her arms, just beaming. I shrank away, knocked her hands off from my face and moved toward the door.

My wife would not hold still.

“Don’t fight this, please. It’s what’s supposed to happen. Today’s my last day.”

“No,” I said. “It isn’t. Stop.”

Pauline’s face hung a beat, then darkened. She turned away to face anywhere. She began singing to herself again, a sound that laid upon the room.

“You aren’t dying,” I said, and then again, and then louder this time. More words came out of me before I had them. I found myself shouting again into Pauline’s chest, pulling at her arms down hard so that she’d listen. When her eyes still appeared far gone, I pushed her, heard her body hit the floor. I kicked her once to stop her from singing still, which did not stop it; if anything I could really feel it now. The sound was gathering inside my knees, flushing out in loops of water. I watched her crawl across the carpet into the living room to where the den was, the mold wall waiting there inside. Her breathing seemed to heat the air between us until with both hands she lunged and closed the door.

✖

I watched my wife wait through that whole evening moving back and forth from room to room. She doted on a wristwatch of her father’s, watching the seconds click past, one into the next. She wrung her hands into a shaking and crossed herself. I tried again to go to her and say a thing to clean or at least mask what was between us but she wormed around my guilt, sliding down straight my arms onto the floor as if made to by magnetism. I tried to keep my teeth inside my mouth. Well after midnight I made us dinner, brought it to her on the floor, her body flexed below the wall, speaking in the baby language. She let the runny eggs and oatmeal cereal fall right out of her mouth. She refused to chew or grip my fingers. At times she went to stay against the window as if looking out for some expected visitor, or rain. She was hardly even blinking.

The hours clicked quickly away.

Soon the whole night was gone and on into another kind.

Pauline kept waiting. She inhaled and held it. She pressed her palms against her thighs.

After a while, she took off the wristwatch and laid it facedown on the table, went on waiting. She was sweating, then she wasn’t.

“It’s just not right,” she said and said. “Not what was wanted, what should have been, for me and anybody, now, forever.”

“Of course it’s right,” I always answered, forcing my voice to come out kind.

When she’d grown loose enough to let me, I tried to make her stand up there beside me but her body would not hold.

“You’re alive,” I kept repeating, as I carried us to bed.

✖

I woke from heavy sleep some short time later to the sound of rainless tremor at the glass. Wind blew dust in at an angle from somewhere above, warm tides of wind and thunder blaming the long side of the house. Light was coming up around the edges of the slurred fields as if they were being opened. I sat up. Pauline was not in bed. I could not feel her in the house. Another feeling led me to the window, where for where the air had curled the curd and heat in, heaving, I could hardly see the world—see where my wife was standing on the barn roof, the mold beneath her grown together, waving. The colored tendrils seemed to slick light up her legs. Her taut yellow dress tattered with holes where she’d ripped to fit it. Her hair blew straight up off her head in laps as if to match her sky-extended arms. Underneath her face was nowhere—I could not see anything but flesh.

I hit my fists against the pane. I shouted knowing she couldn’t hear. Light etched a box around her frame. It tickled at her, cracked and split, held her wobbled, leaning forward briefly, then head-on into our farmland’s blackened splay.

For a long time thereafter, I did not go out—made no move toward the strumming fields to claim my lost wife’s body from wherever it’d hit down. Instead I stayed lidded by the house inside the close walls silent, stood in a room and listened with my both ears to the hot storm beating. Though the thunder grew to shake the gutters, the whole husked click of rooms, the rain wouldn’t come now. The thunder crammed the light, cracking at the edges until the day itself had shot on. There seemed so much light burst through the house’s inputs, reflected in gashes on the endless fields.

In the den I found the mold wall laying face down on the floor. Against the room, the mold had flourished, taken hold of the house’s slim inseam, spreading out now in haphazard tendrils to cake along the inseam of our home, alive. In my mind I could already see it crowding everything inside here, like the outside, like my wife’s wide-opened brain. I felt it cooking down the hallways, over doors and on in spiral with its one unshaking color, though I could not think of which one, or what name. In the mold’s hold I felt the air it touched wrap up around me, its mesh so warm and wide I found it difficult to stand. I was so soft, so full of blank space squirming. The linings of the house like the absorbed breadth of the fields at every inch seemed as if on the verge of splitting with the language of the scrolling mold held in its seams.

I felt my body making talk. I heard my voice aping the child’s voice, as my wife had, as was written in the sod.

For each word I spoke into the wall aloud I felt it there inside me rub, counting quick coming days down in my cells’ vision, where though I had not come across my own oncoming number, had not received it, in my son’s hand, I knew and knew. I felt the drumming of where the date was written regardless of if or when I found it, now with the wall of mold pressed to my face, already eating its way inward upon contact.

I had to rip myself away.

I had to cut and curse the mold with both arms, to free myself there from the house into the day where in gross daylight rooms were blooming, the ground there ever inches closer to the sky.