This essay will appear in Vol. 2, No. 3 of the American Reader, forthcoming later this month.

Everyone appropriates landscapes that are not their own. That’s what it means to exist in the shadow of late-stage capitalism—everything is up for grabs; every window is a line beyond which looting begins. Countryside, cityscape and suburb: refracted through your computer or television screen or car window, these settings are fragments, mirages, cultural tropes, quickly flashing scenes you can shape to fit your needs. But appropriation isn’t just easy, it’s also ephemeral: when you appropriate what you don’t understand, you take hold of a time bomb. One day, unexpectedly but inevitably, the appropriated will confront you—in the clearest possible terms—with the evidence of your own distortions. This is more or less what happened to me in late April, when the New York Times ran a story about the persistence of rural poverty in the United States. The facts of the piece didn’t surprise me—I am from Central Illinois, love the countryside, know rural poverty from a distance. What surprised me were the captioned photographs: stark and beautiful renderings of wooden houses and old brick town squares set against green mountains, bare trees and dusky skies in McDowell County, West Virginia. I was surprised because I’d seen nearly identical images before, watching the Gangstagrass-backed credits for FX’s Justified on Tuesday nights in my room in Brooklyn.

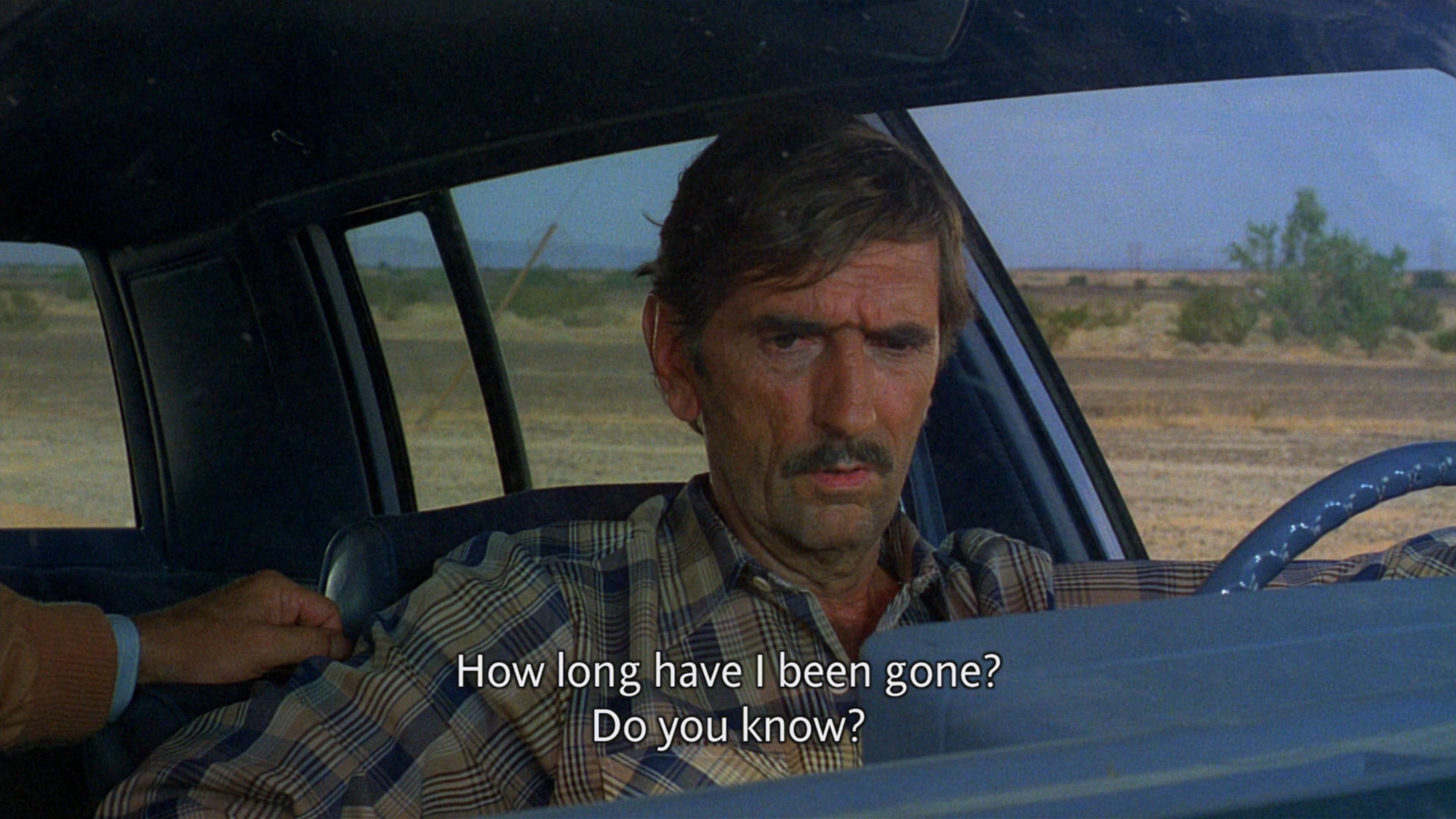

Based on an Elmore Leonard short story, Justified is about federal marshals chasing hardened criminals in the hollers of Harlan County, Kentucky, once the site of some of America’s most vicious coal wars. The main character wears a cowboy hat and the antihero is an explosives expert. The criminals are poor and desperate and also hardened, brilliant operators: they inhabit a parallel universe, where you take your morning coffee black with a shot of bourbon and spend your afternoons plotting bank robberies in the back of the local honky-tonk. The pictures may look the same, but Harlan County is a long way from the reality of McDowell County. Rural poverty in Harlan exists, but as a backdrop, as motive for the hard-bitten personalities we watch onscreen. In McDowell County, poverty is the only reality, and it’s not an excuse to become a hardened renegade. It means welfare, chronic health problems, obesity, a blank and unfocused trudge through the days and months that constitute one’s life; it means homemade biscuits, banjos and the occasional fond memory of a grandparent who lived in the same house or on the same road. Watching Justified, I’d somehow missed the fact that McDowell’s were the real lives being lived off screen, not Harlan’s. I’d taken the show on its own terms, as a window onto an otherwise inaccessible reality—taken it as such, even though the reality it claimed to portray was actually fairly accessible to me, existing as it does on the periphery of my hometown. Call this Appropriative Consequence Exhibit A: paying homage to a refracted version of my own background also meant distorting someone else’s.

Moments of recognition like this tend to sound like problematically simplified hashtag offshoots (“Check your privilege”). But they’re indicative of the predominance of certain tropes, and the erstwhile triumph of these tropes over social and political realities in the collective imagination. The reason I could watch Justified while forgetting about its social implications is that the show manages to make use of the trope of rural poverty even as it quarantines from viewers its real implications. Justified’s idea of rural America, and the idea of rural America bandied about by other, similar cultural products of the past ten years, is rooted in the myth of the frontier, an ontological fantasia in which systemic poverty has no place. Granted, it’s the frontier myth updated to a post-frontier age: the coast has been colonized and the wild, open spaces lay in red-state America, strip-mined and forgotten. But the message remains the one that people in a hyper-complex, over-regulated society have always needed from the frontier: the possibility of an escape hatch, an auto-emancipation from the artificialities, rules, and uncertainties that material advancement and nominal stability bring. That’s part of what makes products like Justified such an easy sell: the makers of the new rural westerns didn’t create the need, or the myth—they just exploited what was already there, what their audience was already primed to want.

I would know. On some days, I’m one sector of the target audience. I’m from Springfield, Illinois, which is not rural, not poor, not plagued by methamphetamine or OxyContin epidemics and not populated by criminals. It’s a city of 116,000, with malls, churches, state government, a solid middle class, a skilled gentry of lawyers and doctors—sixty years of progressive prosperity without too many of its cloudier discontents. But when I arrived at a liberal arts college near Los Angeles and realized that most people there thought the center and south and most of the west of the country were valleys of racist conservatives and pleasant under-sophisticates, my view of the place shifted. Transplanted west, I attached myself to where I came from, not the city but the country surrounding it: beautiful, under-appreciated country that now seemed to me to have qualities its critics manifestly ignored. Not least significantly, the rural Midwest was the antidote to Southern California’s sheer size—its centrally planned sprawl and wild commodification, its eight lane expressways and giant Best Buys and theme-park movie theaters facing down one another across a single parking lot.

Home on break, I’d feel connected to the flat, manageable landscapes and two-lane interstates, the farmhouses and small churches you could see as you followed I-55 down to St. Louis, the bonfire smoke you could smell in the humid, green fields just outside the city in summer. I’d get in my Rav-4 Toyota and drive, past grain elevators on single lane roads with names like Gudgell and Ethel, past dying four-hundred-person towns like Hettick and Salisbury, past Farmer’s Point cemetery and the Boy Scout trail, down into a dip in the road and past a stream and then, suddenly, a scene the Hudson River School artists could’ve painted if they’d come west a few more states in 1820: a flat, thick, fertile plain cupped by a hill, creating a spread of green valley, dotted with mis-formed trees. Large new white-brick houses overlooked that valley on a high curve to my left, but they weren’t suburbs, just diminutive participants in the panorama I’d discovered as it got to evening, as the hazy, heated sky softened to a robin’s-egg blue and the cicadas came out.

This narrative arc is a familiar one: the coastal transplant escaping, however briefly, back to the stable order at the edges of his childhood. The archetypal lapsed Middle American is Nick Carraway, coming west on the train at the end of Gatsby from the distorted cities of the east, where nothing seemed to match, back into a country of “bored, sprawling, swollen towns beyond the Ohio” where he could understand things, where he could be himself:

When we pulled out into the winter night and the real snow, our snow, began to stretch out beside us and twinkle against the windows, and the dim lights of small Wisconsin stations moved by, a sharp wild brace came suddenly into the air. We drew in deep breaths of it as we walked back from dinner through the cold vestibules, unutterably aware of our identity with this country for one strange hour before we melted indistinguishably into it again.

Except for the fact that image proliferation has accelerated to the point where I can see a street view of Gudgell Road from my laptop in Brooklyn Heights, there’s not much difference between Nick’s reverie and mine. They are reveries of those who “pass through,” who see the rural landscape as an antidote to the crowded coastal metropolises, and the mentalities and moralities those metropolises produce. They are conflations of personality, fate, and landscape: driven by need, denuded of actual content, laid bare to the pervasive sentimentality that is the flip side of imagination in an image-saturated society. It’s not like I didn’t know, more than most, what life was like for people in rural America—the forgotten white and increasingly Latino and African immigrant underclass, the drug epidemics that made national news and then didn’t anymore, the onset of agribusiness, the hollowing sense of being used as props on Fox News and yet never really noticed, of lacking any kind of spokesperson in the great national pastime of ‘attend to my issue.’ But the mounting bad news was easy to fold into the same image as the valley sunset, though the color tones were darkened, like the beautiful, bleak, garish, survivalist pictures in Justified and the photo carousel of the New York Times. Watching Justified sharpened the image I already had of the wide-open spaces—gave it an edgy, realist vibe that the Hudson River school reveries lacked, validated my aesthetic preference as unsentimental and culturally interesting. All of which poses a problem: if those of us who are stirred by America’s forgotten rural corners can’t afford to see their reality, is there anyone who can?

The answer would seem to be “no.” We’re living in a golden decade for rural escapist fare: the latest, most extreme iteration of a cultural construct that effectively removes people living there from society’s list of concerns. The effect of these savvy new Westerns is, in some ways, even more insidious than their progenitors’, since they incorporate the countryside’s decline into the genre’s standard narrative, and, in so doing, effectively ignore that decline by aestheticizing it. Now the cowboys aren’t discovering the west, they’re preserving it, this parallel society living alongside ours, all unknown and neglected folkways and byways, comfortingly unchanged in the face of global hyperactivity. These new Westerns have relocated the drama to the forests and hills of the backcountry—upstate New York and Alaska, the Midwest, and, especially, the Ozarks and Appalachia. Our heroes, hardened men and women whose parents and grandparents grew up here, are tenaciously maintaining their lifestyle in the face of modern life and—this is the point—we can’t and won’t imagine them any other way.

Strikingly, this recapitulation extends across the spectrum of creative engagement, from the popular to the serious. Justified, a glossy, smart-talking commodity, is located roughly at the center. At the high end are independent films like Winter’s Bone and Frozen River and Beasts of the Southern Wild, as well as books like Andrea Portes’ Hick, Frank Bill’s Crimes in Southern Indiana, Daniel Woodrell’s novel Winter’s Bone (the inspiration for the movie), and Donald Ray Pollock’s Knockemstiff. At the low end are Discovery Channel’s Moonshiners, MTV’s Buckwild and A&E’s Duck Dynasty. If you had to coin a phrase for the genre, it would be “rural noir”—with a few exceptions, there’s a dark, criminal cast to these stories. Many of them center on crimes, normally drug-related; others show people fooling around, drinking and robbing convenience stores. The protagonists are mostly white, with a smattering of blacks, Latinos and American Indians. They run the gamut from old to middle-aged to young, and attractiveness is not a high priority. Their lives are exercises in preservation—they use the skills they’ve inherited to preserve what they have, which is some degree of independence in the ruins of post-industrial capitalism.

Moonshiners sets the terms of this formula in its opening credits: “In Appalachia, moonshining is considered by many to be a way of life. It is also illegal.” Already we’re off the beaten track (“Hidden deep within the hollows of a forgotten corner of America”), following people (“the renegades who call this place home”) for whom “a battle is about to begin” between the old ways (some of America’s first settlers, they say accurately, were moonshiners) and the new; natives defending their identities, for better or for worse, against the outsiders. Moonshining is a good fit for this kind of theme—an elaborate, occult rite passed on through the generations—and some of the most hyped parts of the show revolve around never-before-seen brewing processes. So is mudding, on the more obviously commodified Buckwild; duck hunting in Louisiana, on Duck Dynasty; immigrant trafficking in upstate New York, in Frozen River; meth-making in the Ozarks, in Winter’s Bone; and violence in the Midwest, in Crimes in Southern Indiana and Knockemstiff, which begins: “My father showed me how to hurt a man one August night at the Torch Drive-in when I was seven years old. It was the only thing he was ever any good at.”

Sometimes the tribal aspect is so pervasive as to pre-determine the plot. In Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone, Ree Dolly contemplates her extended family, a motley collection of criminals so ruthless that they killed her father—their own flesh and blood—for turning police informant. Her attempts to trace the ontology of this family send the novel spinning into the realm of folklore:

After the bitter reckoning many Dollys fled from Hawkfall to caves, and this slope was where they congregated to live through that first winter of exile. Her Dollys were among those Dollys. Her people had lived hunkered in these caves for a mean winter and late spring, kids breathing rattly, grannies spoiling in the dank, the men with each breath refreshing that great snarling tribal anger that Haslam had tried to preach away from their hearts and habits.

“It was those brute ancient ways,” she realizes, “that broke fresh over her world at every dawn and sent Dollys to let the blood drain from Dad’s heart and dump his flesh somewhere hidden from path and cloud.”

These mythic, indigenous portraits are less strongly rooted in Appalachia and the Ozarks; and when—as in Donald Ray Pollock’s Knockemstiff, Andrea Porter’s Hick and Frank Bill’s Crimes in Southern Indiana—they serve as the settings for the modern rural noir, tweaks are necessary. Here there are no sweeping vistas, no vague, incestuous pasts; recourse must be made instead to the flat, grimy reality of the everyday, and to vague, violent futures. Woodrell’s primordially dramatic language is maintained, but used in the service of a slightly different story which, ultimately, is basically the same story: death, sex, and talk of God concatenated to resemble a dead-end mythical narrative, one that takes the baser elements of Ree’s story to their logical, deadening extreme. The reader of these tales is meant to assume the wide-eyed, cross-bones-style position of the observer—the observer of spectacle.

Take Frank Bill’s description of the death of Able Kirby at his wife Josephine’s hand:

It was as if God himself had shot the son of a bitch from the sky. But the good Lord had done no such thing to Able Kirby. His body lay face down, ears still ringing from the small-caliber gunfire that dotted his upper back, chest, and gut. Blood etched a path behind his work boots, leading all the way to the flaked wooden screen door of the house from which Able had stumbled…Today he’d sold his granddaughter, Knee High Audry, to the Hill Clan to whore out. Needing the extra cash to help pay for his wife Josephine’s cancer medications. Yeah, he thought, I’s a son of a bitch.

Meanwhile:

Josephine stood in the kitchen smelling the spoiling skin that hung loose and gray like dry rotted curtains on a rusted rod, wishing she’d stopped Able before it got this far. Thinking of how she lay in bed, night after night, listening to him worm from beneath the cloth, cross the floor, the squeak of hinges to the bedroom where their granddaughter slept. Jo would work her way out of bed, inhaling hard and grunting…That’s why she began sleeping with the Ruger beneath her pillow. A .22-caliber pistol she’d wielded to remove varmint and snake from the chicken house and garden. She knew she’d grown too weak to physically do damage.

The only reason this isn’t pornographic is because it’s cartoonish: granny in the kitchen with a pistol and a breathing machine. It’s unapologetically, hyperbolically, repetitively, sickeningly exploitative. But whether here or in Ree’s Ozarks, whether in porno-realistic mode or lushly purple prose, the actual protagonist is the same: an authentic culture that can, through shrewdness and grit, survive the jarring shocks delivered by an inhuman market. Of course, the characters use the market to the extent they need to—they manufacture meth, they buy guns to kill their spouses—but in the end it comes down to Josephine protecting her granddaughter or Ree enjoining her hardened kin to remember their shared roots. Like Justified’s Harlan matriarch says to the coal company representative:

My people have been here for 200 years, Miss Johnson, and we will be here once your people have come in and taken what they want and left. Nothing changes up here, not really. I’ve seen the story played out time and time again before, as it will happen again in times yet to come.

Even the sunniest, least noir-ish, most aggressively commodified stories—Buckwild and Duck Dynasty—come down to the issue of preservation. The kids on Buckwild put off college and escape into the hollers, messing around in the ways their daddies have done before them. The appeal of Shain Gandee, the star of the series, is rooted like most reality stars in his apparent authenticity: he really would rather mud through the hollers and swill Bud-Lites than do almost anything else. The case of Duck Dynasty’s Phil Robertson is more muscularly escapist. Robertson was the first-string quarterback for the Louisiana Tech Bulldogs, but he turned down the opportunity of going pro. Instead he went back home and manufactured a call that more exactly reproduced the sound of a duck. His son Willie turned it into a multimillion dollar business, and Phil used the money to set up a giant, irrigated compound in Southern Louisiana where he teaches his grandchildren survivalist skills and hunts ducks. It’s a fairytale, complete with moral: Robertson preserves his blood ties, rugged independence, and culture, however he can.

Readers looking for diversity might be surprised to find it thrives here: gender, race, and class fit neatly into the genre’s hermetic parameters without actually challenging them. Women are more often than not the centers of narrative focus. The stars of Frozen River and Winter’s Bone are a middle-aged and teenage woman, respectively: both actresses, Melissa Leo and Jennifer Lawrence, were nominated for Academy Awards for their roles. Hick and Beasts of the Southern Wild are about young girls, age fifteen and six, respectively. Even when they’re not in the center of the frame, women are powerful presences. Margo Martindale picked up one of Justified’s two Emmys for her portrayal of the hardened crime matriarch who cuts a deal with the coal company; in seasons 5 and 6, Academy Award-winner Mary Steenburgen portrays a criminal mastermind who ran her husband’s business empire behind the scenes; and Justified guest star Dale Dickey’s turn as a Dolly family matriarch in Winter’s Bone is the film’s most chilling performance. Women in these stories have it rough, but they make do—hardened, unapologetic, protective of their family and fiercely determined to survive. Their husbands are nominally in charge, but they’re the lethal quantities, the guards and avengers. You would never think of offering them aid—not Josephine standing with her gun in her bedroom avenging her granddaughter or Ree trying to save her siblings and her land—they’d turn you down; they’re making it on their own. Their destiny got molded at their births, and they like it just fine. Like Ree says, with a smile, “I’m a Dolly, bread and buttered.”

To the extent that minorities surface, it’s in similar molds. Justified Season 3 has a formidable black community that has lived in Harlan County for generations and relies on butchering pigs and selling drugs to support their existence and keep out intruders. In Frozen River the supporting lead is a Mohawk woman, Lila Littlewolf—she’s hardened, she’s suffered, she’s capable, she’s very occasionally maternal, she bonds with Melissa Leo’s character over their shared struggle to survive. Probably the most elastic character in the minority pantheon is Hushpuppy, the six-year-old in Beasts of the Southern Wild, which is itself probably the most flexible entry in the rural noir genre. It is set in Southern Louisiana in an impoverished yet spiritually sturdy community of mostly blacks and a few whites living on an island below a levee; their predominant activities are fishing, drinking, scavenging, and practicing a folk religion. When the community is threatened by an impending storm, everyone joins forces: the movie traces their struggle and survival through Hushpuppy’s eyes. The film stretches the bounds of the genre because Hushpuppy’s six: she’s determined but not hardened, with a child’s sense of pervasive wonder. The community is different, too, than the white renegade counterparts—there are fewer guns, more Blues and zydeco. And yet it’s the same formula: a hardened community, downwind of civilization, enduring on its own. (It’s worth noting that Beasts of the Southern Wild has its own derivations—Swamp People on the History Channel is the most popular.)

The attitude Hushpuppy takes towards the folks upriver, on the other side of the dam, is representative of the genre’s approach to class differentiation: they’re rich folks, privileged, not survivalists, irrelevant to her operations. To Ree in Winter’s Bone, to the criminals in Justified, to the killers in Knockemstiff and Crimes in Southern Indiana, to the “renegades” in Moonshiners and Buckwild and to Phil Robertson in Duck Dynasty, modern cultural complexities are irrelevant, unimportant next to the simple, difficult business of hacking your own way. They’re best avoided or ignored—submitted to only briefly when absolutely necessary. Phil Robertson hates getting his photograph taken, Ree hates talking to the law, Shain Gandee doesn’t like to work. It’s the perfect encapsulation of the American nativist dream: a shared culture negating class and its contradictions. And it’s an attractive fantasy—one that presents itself as hard-edged and existential and down to the bone, that enlivens you with its tribal, primal power. Watching it, you can lose yourself in a feeling of release; you can forget, for a moment, that you are an instrument in a viciously complicated, hierarchical, professionalized, globalized system.

This cultural construction is a hard one to drill through and repair, however innocent your intentions might be. In early summer of 2008, appearing at a private fundraiser for wealthy donors in San Francisco, presidential candidate Barack Obama of Chicago, Illinois, made the following controversial statement:

You go into these small towns in Pennsylvania and, like a lot of small towns in the Midwest, the jobs have been gone now for 25 years and nothing’s replaced them. And they fell through the Clinton administration, and the Bush administration, and each successive administration has said that somehow these communities are gonna regenerate and they have not. And it’s not surprising then they get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy toward people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.

What’s striking about the comment, from an analytical perspective, is that it’s uncontroversial. The rural middle class has disappeared, a symptom of the disappearance of the blue collar jobs and unions that supported them; they have been used and neglected by centrist and Republican politicians for a quarter-century; and the only kind of solidarity that remains for them is to take an increasingly and understandably defensive cultural stand. “Guns” “religion” and “antipathy to people who aren’t like them” are, not coincidentally, the premises of rural noir.

The problem is, of course, the perceived tone—the sense of someone providing sympathy by seeing, or at least portraying, his subjects as caricatures of themselves. Is it really fair to boil down people’s lives, in their complex entireties, to clinging and bitterness, or explain away hunting or church-going as responses to economic dislocation? Probably the fairest read of the comment is that Obama was trying to bridge a divide between two possible voting blocs by explaining rural Americans’ situations in the language he thinks wealthy liberal Northern Californians can understand. But, whatever the intention, it’s the comment of someone who’s taking rural noir’s premises for granted, but putting a negative rather than a positive spin on them. Sarah Palin’s response at the Republican National Convention falls within the same dichotomy, but sunny side up:

I guess a small-town mayor is sort of like a “community organizer,” except that you have actual responsibilities. I might add that in small towns, we don’t quite know what to make of a candidate who lavishes praise on working people when they are listening, and then talks about how bitterly they cling to their religion and guns when those people aren’t listening.

She doesn’t offer a rebuttal, she offers a reversal, a mirror image. Working people might be poor, but they’re proud of their culture. It’s not a condescending-sounding verbal construction like Obama’s, but, given Palin’s background, it’s a hypocritical one. This is a woman who, as Mayor of Wasilla, systematically destroyed whatever small town cultural solidarity existed there in order to turn the town into “a big ugly strip mall from one end to the other.” (This in the words of a current Wasilla councilwoman.) Palin introduced into Wasilla’s sleepy politics a sharply ideological, anti-government, evangelical posture that divided the town; she abolished business inventory and personal property taxes; she rezoned land from residential to commercial and from single-family to multi-family to attract Subways, IHOPs and condominiums; and she cast the tie-breaking vote to stop the city from adopting building codes. She may be a political opportunist who can pitch a good line, but she thinks like a business-oriented, middle-to-upper-middle-class Republican.

But it’s not hard to see why Palin’s offering is more appealing than Obama’s. (And why Obama, winning Pennsylvania, lost its rural counties decisively.) She might rely on caricatures, but they’re caricatures that make you feel, if you’re a person from rural America, that you and your life and your vote matter. Remember, everything’s up for appropriation in late capitalist America, even if you’re appropriating someone else’s appropriation of your own life—and, at this point, what other option is being offered to someone from Wasilla?

This problem also ensnares people who speak for the region with more purity of intention than Sarah Palin or Phil Robertson. Most of the people who make films and write books and advocate for rural America see it as more than a blank slate for personal projections or to gin up a willing audience. Donald Ray Pollock, Daniel Woodrell, Courtney Hunt, Andrea Portes, Frank Bill, Jennifer Lawrence—these are people from, if not the hollers, then certainly not the coasts. Some of them might have distilled their backgrounds’ lurid and romantic elements to the point of exploitation, but many still live in the places where they were born, still see themselves as bearing witness to the places everyone else forgot. Nonetheless, these are artists working against ingrained constraints: how do you sell America’s forgotten spaces to the public, if not by using the one thing they have going for them, which is their frontier resonances? And isn’t it preferable to present your people in the strongest possible light, given that you’re fighting against a tide of neglect, indifference and condescension? Three-dimensionality has been denied them, but if they’re doomed to be cardboard cutouts, can’t they at least be survivors? This is the Walker Evans problem: the photographer who tried to bring attention to rural Americans’ Depression-era poverty created images of suffering that were, in a sense, too compelling, too romantic, too magnetic. To be captivated by one of his photographic accounts of poverty was to be ensnared in a perverse, moral-aesthetic dilemma, since it’s hard to alleviate a socioeconomic problem while also fetishizing it.

The human consequences of this dominant construction are the hardest to grasp, in part because so little of the actual reality of rural Americans’ lives has percolated through the media. But an extreme, grotesque and compelling example is Shain Gandee, the de-facto star of Buckwild, someone at the yawning maw of rural pop culture who didn’t last long enough to catapult himself into the firmament. Here was a 21 year old who appealed to the reality show scout traipsing through West Virginia in search of inspiration because of his truck: “muddy, a rebel flag in back, squirrel tails hanging off the antenna.”

“We took [the producer] up on top of the hill in Shain’s truck,” [Shain’s friend] Joey recalls, “with two or three other girls and another dude, and we threw them all in a mud hole, and they mud wrestled, and we just had fun, and we went through a mud hole a couple times in our truck. He was like, ‘You all are crazy.’ ”

Shain was a gold mine of “realness.” He liked to mud wrestle and he liked going mudding, or driving through mud holes in his truck. Also:

When he was a kid, family vacations meant getting in the car and driving to the first intersection, where Shain or his sister, Shalena, would choose left or right, and they’d just go, not knowing where they’d end up—a cave, a waterfall, a lake. He and Joey had grown up constantly breaking bones and getting stitches; once, Shain got bit by a copperhead snake. At Sissonville High, you knew when Shain arrived in his Dodge Neon because he’d skid sideways into the parking spot. He loved cars and making things—friends called him a “redneck MacGyver.”

Shain was real, or as real as you can be when you build your presentation around confederate memorabilia and MacGyver—one part genuine, one part cultural knockoff. But who knows how his personality would’ve shaken out, how the fun-loving, back-country, spinning-off-into-the-holler-faux-wildness would have resolved itself when he was twenty-five, wanted to marry, needed a mortgage? We don’t, because his authenticity was taken out for harvesting by MTV and suddenly these personality features were the sum of his person. He was the reason the first season of Buckwild became MTV’s flagship new show. And then he became the reason the show ended. A few days after filming for season two began, Shain went drinking and then mudding in his truck with his uncle and a family friend: three days later they were found in the truck, its tailpipe stuck in the mud, dead from a carbon monoxide leak. For a week the cast thought the producers might renew the show anyway, but who were they kidding? Shain had taken the lifestyle he portrayed in hour-long increments to its logical conclusion, and who wants to learn about that? Who wants to dredge up unexamined and unanswerable questions like: was that even his lifestyle, or was it a couple of preferences the market fetishized and encouraged him to run with, to his death?

Shain Gandee is an extreme case, but he’s also a perfect encapsulation of the process. Some rural Americans are appropriating extreme versions of their own culture because it’s the only future that’s being offered them, because the market has increasingly reduced their prospects to a forced choice between life as a socio-cultural non-entity or a one-dimensional product. For all intents and purposes the complexities of their lives have receded out of sight and mind. People like Barack Obama wish they could help but are bound to be misinterpreted; they’re outsiders trying to sell the validity of a culture to parts of their base who instinctively dismiss it. People who like the frontier vibe but dislike the Palin/Robertson mentality can drink Maker’s Mark bourbon for $30 a bottle, watch Justified, feel a sense of loyalty to the place they came from and forget about the people who are actually living there.

In the meantime, the country’s forgotten spaces are filling up with meatpacking plants and African and Latino immigrants who, along with poor whites and African Americans, work long hours under unsafe conditions without labor protections. According to the same Times article that jarred me: “Of the 353 most persistently poor counties in the United States — defined by Washington as having had a poverty rate above 20 percent in each of the past three decades — 85 percent are rural.” In his 2009 book Methland, the journalist Nick Reding describes the ravages of methamphetamines in rural Iowa. He notes that most of the people who started taking the drug did so because it helped them stay awake during their twelve hour shifts at the local factory. Then it turned into a means of mental and emotional escape. These aren’t people who are attending college, or who colleges are even trying to recruit—these are people who spend their Animal House years formalizing membership in a permanent underclass. You could say that small town people have done this to themselves, but you’d only be half-right: they were given one image to choose from, and they took it and ran.

Rural America, then, needs a new image, a truer image—not the frontier culture’s gritty existentialism, but something that opens up on what is actually happening there, that does not reduce its inhabitants to hardened latter-day cowboys or bitter gun-clingers, depending on who is telling their stories. This is an artistic and observational challenge that transcends the particular issue of rural poverty—it’s about the distorted perspectives we bring to everyone’s lives in a society that runs on recycling and re-appropriating other people’s lives through images. But our collective refusal to acknowledge the plight of the rural poor in this country suggests it may be the place to start. It is, after all, our refusals that most reveal us, that most reveal our intentions. What does it mean about our ability to recognize our differences, as well as our ability to transcend them, that we’ve collectively chosen to remain locked in this constant fetishization of rural poverty?

Most pressingly, it is a question of action. In a society where the market reduces people’s lives to the sum of their most sentimentalized characteristics, where we all buy into particular commercialized fantasies at the expense of other people’s realities, it’s past time to ask ourselves how we can begin to acknowledge the lives of others in sufficient complexity, in such a way that there might be the possibility of compassion, the possibility of conversation, of action, of redress. To put the problem most basically: Shain Gandee’s is a particular story, but, in a society in which capitalist media saturates and divides us, it’s a glaring example of the challenge of recognizing each other’s basic humanness and working to create conditions where that humanness can exist. And, for all of rural poverty’s complex causes, beginning to re-enfranchise the rural poor from their silent exile and back into collective discourse means something very simple: blinking and taking a closer, harder, more honest look.