Photographs by Samantha Zighelboim

Photographs by Samantha Zighelboim

Middlemarch: an exhibition by Simone Kearney

Berl’s Poetry Shop, 126A Front Street, Brooklyn

January–March 12th, 2014

Berl’s Poetry Shop located in Dumbo has emerged from nowhere it seems to become one of the most exciting venues for poetry in New York City. No easy feat considering the long-standing wealth of options. Owned and operated by poets Jared White and Farrah Field, Berl’s features an exhaustive inventory of poetry titles and chapbooks from small presses and independent publishers, and strikes me as the happy NYC-equivalent to Amherst’s beloved Flying Object (a book shop, event space, printing operation in full service to the muse). Recently, they’ve begun showing art on their clean-white boutique walls, and the current show, Middlemarch: an exhibition by Simone Kearney is up (appropriately) until the middle of March.

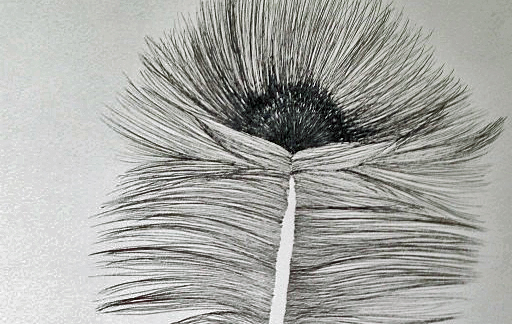

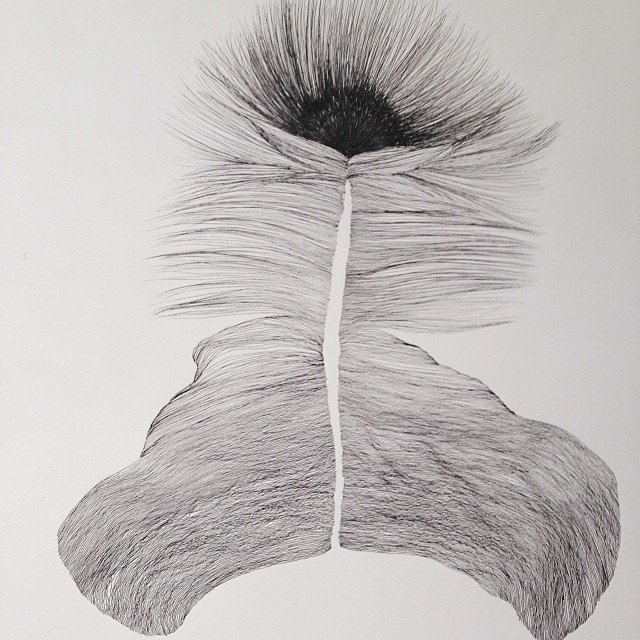

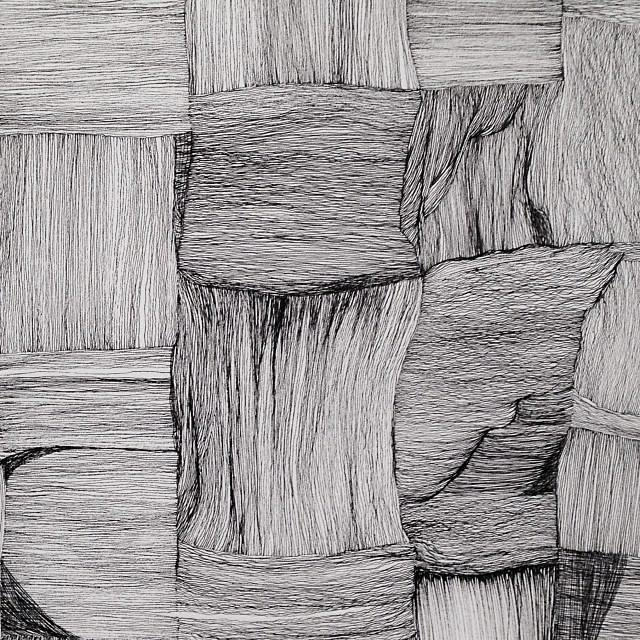

It’s a show not to miss. Though I’ve known Kearney for over ten years, nothing could quite prepare me for the shock and awe of her first featured gallery showing of paintings and drawings. Composed while listening to George Eliot’s masterpiece read aloud in the background, Kearney’s artwork feels literary without ever becoming literal (the shared enemy of most derivative inspirations). The show’s title is evocative and allusive to a classic text, though never quite locatable in any of the abstract paintings and semi-figurative drawings lining the walls. Instead, the show illuminates an interior space devoid of faces or figures, one astoundingly mental: the meticulous line work and crosshatching of the drawings lead me to believe the artist is a world-class obsessive fretter, like the league of lovelorn characters that fill Eliot’s pages, all in their way trapped in unhappy marriages, impossible romantic fixations, and finally, inside the fictitious provincial town of Middlemarch itself.

Kearney’s work, however, is anything but provincial—though some of her images suggest the infinite delicacy of birdlike wings, tissues and muscles that might populate an ornithologist’s anatomical textbook. The paintings recall the weighty whimsy of Philip Guston, the exploded naturalism of Joan Mitchell—but I find myself at a loss really to ‘place’ them by school or style. One thing’s for sure: Kearney’s handling of paint and abstract shapes is unapologetically beautiful to look at in a recent contemporary art world where the sensual seems to be pretty taboo. Perhaps, like the juggernaut intellect of the inward and trapped Dorothea, these paintings and drawings are a testament to the power and curse of a mental life that we end up leading, even if we’re lucky enough to have one, quite alone.

✖