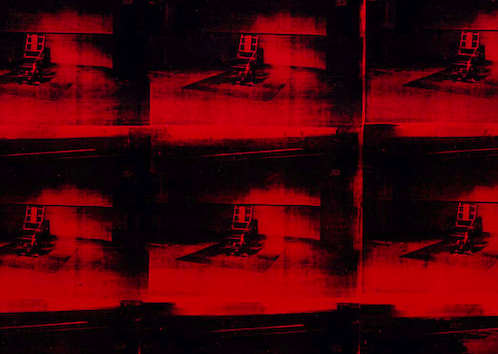

Death & Disaster Series • Monk Books • 2014

Lonely Christopher’s poetry isn’t polite. In fact, it will most likely put off a good deal of readers with prissy tastes because his poems actually want to get to know you, live beside you, demanding intimacy, valuing as much the pleasant dead time between our personal and global catastrophes as the catastrophes themselves. Accordingly, his first full-length collection, Death & Disaster Series, is full-length indeed—nearly two-hundred pages. This is quite indulgent, brazen and I would argue—given the aesthetic attack of the work—necessary. “Series” is the sneaky key word of the title. Like the Roman Catholic God, this book’s both one and three: “Poems in June,” “Crush Dream” and “Challenger” respectively. These divisions never feel arbitrary, in the way too many contemporary poets park their poems down in convenient, attention-span-courteous groupings. The result is a sharply integrated and commanding whole, a triptych of love, poetry and grief orchestrated around the time each section was written: the June before, the August during, and the months after his mother’s death.

“Poems in June,” mostly shorter lyrics, has within it the bounce and jaunt promised by such a phrase. One of this poet’s astonishing graces is to construct a lyric from only a few lines and convey inside them an entirely clear and striking sensory experience, traumatic impression, whimsical middle finger, love song, letting the image or confession stand without any intermediary explanation. True, this seeming lightness can feel like you’re looking over the shoulder of someone as they throw off a sketch. But the gain from such directness is that Christopher has no agenda but the pleasure of honoring the immediate, the at-hand, the ephemeral. I believe this painterly, observational vibe regarding poetic composition links Christopher to the genius of W.C. Williams and one of my favorite poets, James Schuyler—though neither are as continually morbid and perverse inside their uniquely American grain of lyric impressionism. If Christopher’s poems don’t aspire to smoothly croon over or dryly document roadside vegetation, they’re not without their own sense of evocative prettiness:

Easy Poem in June

Not like you

I like climbing down a ladder

made of gold into

Hell

some people have died

for this country.

Pretty phrasing, that is. Yet not so pretty content. It’s the kind of combination, to my mind, that made Hank Williams so memorable: a sunny voice atop desperate lyrics, lonesome melodies. “Easy Poem in June” emphasizes the discomforting misdirection that the poems favor: let’s start light then nosedive, from golden ladders to hellish patriotism. Most people might think of “June” as the wedding-bell subject matter for hot-blooded singers from Memphis. For Christopher, it becomes a mantra that darkens almost every poem.

You Have Ideals

You have ideals and I

have June

June is not an aspiration

but a thing to suffer

so I have June

you take whatever you like.

There is no Christian God.

Another, shorter screech:

Blow Up

See the girl in her hijab

she blew up.

America in June.

June is “gross June / against us / in economy” (“I”) and “June how does one write in June / in this sick planet I want to be / famous I want the poet’s fame” (“Desperation”) and “June vituperates / drizzle under the sun” (“Saturday in June”). Most of us are at least tempted by mother nature’s serotonin-infusion to forget ourselves, forget the ugliness of the rest of the world, in June. Poetry is too often a place where people also want to forget the ugly, of sex, of politics. Instead, Death & Disaster Series roots down and mutilates the psychic debris left by family, God and country. What the poet finds there is demented candor, full of filth and desire and inescapable dread:

I love a boy’s cock

it makes me think of AIDS

it gets me off.

My mother dies.

Susan I can’t think about you

till I see you well enough

inside it

and around

my God

death just think of it my G-d.

(“The Lollipop Aftermath of the Nigh Before”)

Susan, the poet’s mother, died in August of 2011; the first third of Death & Disaster Series was written before her passing, the rest in its wake. The resultant poems agitate and twitch and jump. They manage to capture the same anxiety that ambushes yet motivates all writing, in a way, finally. Yes, our banal, sometimes sublime, sense of mortality. Seeing as we’re mortal, better write something down. “The End of June” is a marvelous example of counterpoint to the shorter poems, with a much loopier and more manic syntax that warps—delightfully—many of the longer works in the book. It’s also one of my favorite poems in the book:

girlish poetry pervs round itself

chancing over tableaus whereat

a sculptural life of some figurine

brings me to justice that I might

take the face the way his shape

skeletons into my unlikelihood

for I cringe with self-recognition

I am so June for a new stranger

a paragon of boys swaying up

the corner of a stinky old club

the way his eyes burst back to

themselves as if involving seas

in their insouciance and drama

What distinguishes Death & Disaster Series from the other contemporary poetry books, especially first collections, you’ll read this year is its range, its assimilation of discordant tones, shifting line-lengths and graphic subject matter. Christopher, perhaps like no other poet his age, fuses modes of narrative style—confessional, transgressive, erotic, bathetic, abstract, cubistic, vatic, schlocky, highly literary—within poetry until it all feels like a diabolic mélange. And while I suspect he will have no trouble finding attentive readers young and old who are tickled and titillated by his sensationalizing directness in matters of fucking and grieving, by his pronouncedly queer and anti-capitalist politics, I think what I find most refreshing about this very long book is how unapologetically quiet, almost delicate many of these poems are.

Many of the most exciting poets I know have been publishing equally lengthy books as of late: Timothy Donnelly’s The Cloud Corporation, Ariana Reines’ Mercury, Lyn Hejinian’s The Book of a Thousand Eyes. The risk to such endeavors is real because poems like their poets can end up being repetitive, uneven and vain. Lonely Christopher’s first book of poetry by all means plays into these dangers but its ability to confront tragedy and re-organize experience shows just how alive and unstoppable American poetry in our time continues to be.

✖