E! Entertainment • Wonder Books • 2014

Did documentary poetics start today or yesterday, or sometime in the twentieth century as all the arts inevitably scrambled in the aftermath of film’s fractured syntax? Perhaps it was Dr. Williams overhearing his Polish mothers in Rutherford, New Jersey, or even earlier, with Walt Whitman, poet-journalist, cruising across the slap and blab of the pave. Maybe it all starts with Sappho (like everything else in poetry) as she ogled some young maiden’s instep and arch and captured its affect on papyrus—You burn us. Recently, a lot of attention in the poetry world has encircled the radical practitioners of copy-and-pasting, texts found or slyly altered, analogous to Duchamp’s ready-mades and assisted ready-mades (cheater!). While much of the riotous attention has gone to Kenneth Goldsmith (“I don’t write poems”) and Vanessa Place (“Never apologize, never explain”), I find it’s always nice to scale back the conversation in time and remember that if conceptualism is at least a hundred years old, contemporary avant-garde interventions of appropriation and collage—the key ingredients of most “do-po”—must include Eliot Weinberger (whose Poundian essays do not ask to be read as poems, but I happily insist on their behalf, saner and subtle in a way the mad impossible Cantos cannot be) and Susan Howe (whose poems read like fragmented prose, and vice versa). Or Harry Mathews and other Oulipian masters, the Guy Davenport of his essays, the Robert Polito of Hollywood & God, a dozen other worthy candidates. Beyond the putzing around of critics’ perennially obsolescing question, But is it poetry?!—yes, beyond this, a mantra I return to amid the ruckus and fray: good writers pay attention just as good writing pays it back (even boredom’s absolute kelvin is economical). I don’t necessarily know, or care to know, to what, and there are endless hows and whys which each generation modifies and revises, but this seems to be a safe enough universal. Even as fastidiously boring an artist and wonderfully laconic a writer as Mr. Warhol is after all nothing if not the proverbial attention-whore. And who of us in the Social Media Age isn’t required to be so, now?

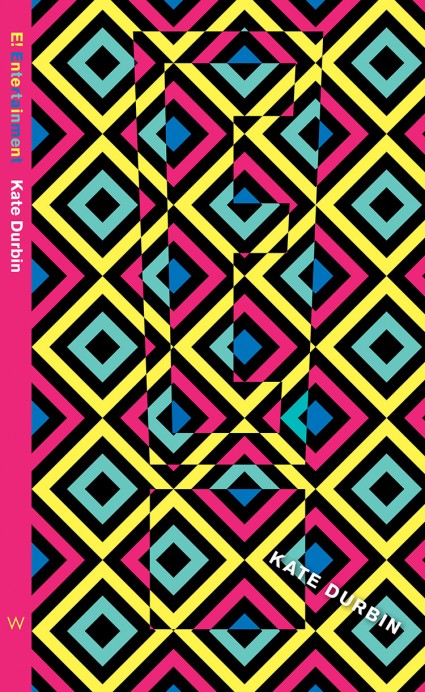

Enter into the arena Kate Durbin, whose latest book, E! Entertainment has just been published by Wonder Books, demonstrating seven years of atomically precise attention paid to the linguistic ecosystem of reality television. Deliciously designed in the prettiest of pink pages by Joseph Kaplan, E! Entertainment arranges, annotates, reports, and represents our favorite national pastime—sitting on our fat asses watching the boob tube. But Durbin’s presentation of eight “channels” (sections titled “Wives Shows,” “Lindsay’s Necklace Trial,” “Anna Nicole Show,” “The Hills”) in close to two hundred pages is anything but passive or flabby. Sometimes, apropos Pound’s review for one of Frost’s earliest collections, I can’t help being uninterested in reading about many of the ostensible “subjects” in this vernacular experiment of total devotion. But that seems as relevant as whether or not you want to hang out IRL with this or that New England farmer. A poem is a poem is a poem. Hart Crane once wrote, “Unless poetry can absorb the machine, i.e., acclimatize it as naturally and casually as trees, cattle, galleons, castles and all other human associations of the past, then poetry has failed of its full contemporary function.” To which we must now say, “Unless poetry can absorb Renee from Mob Wives [a favorite reality-TV crazy of mine], LiLo, Louis Vuitton, Courtroom TV, and a ‘large Hello Kitty pillow’ as casually as machines and bridges and locomotives, then poetry has failed of its full contemporary function.”

Kate Durbin’s stance, ridiculous as it may seem, nevertheless extends from this ambitious Cranean insight. Reading her one knows that the future of poetry must always invent through embracing the seemingly unpoetical material of the present. Of course, to focus so much on “subject matter” is an inevitable ruse triggered by such work—isn’t its whole provocation the decision to emphasize this or that “content” (a Modernist dirty-word)? For many readers, partisans and balkers of Durbin’s aesthetics alike, I can’t help feeling it must be, in part. Part of the Duchampian and Warholian demolition against the preciousness of a certain high-serious formalism (the literary equivalent being New Criticism) engineered generations of readers into thinking that to be caught talking “about” the signifieds of an artwork was a big no-no. But when you have an inverted toilet or a giant commercial soup can staring you down, it’s hard not to feel the joyous contaminating rush of everyday, marketable banality pushing back on the imagination. That is, subject matter itself. Many of the compelling poets of my generation—Durbin is among them, but I think also of Ariana Reines, a very different poet—quiver for me along a particularly trendy poetics right now: the return of hyper-real content to poetry. Which is to say, in silliest shorthand possible, more O’Hara, less Ashbery; more Creeley, less Olson; more New Narrative and Performance Art, less postmodern theory and Abstract Expressionism.

A good deal of young poets today seem to be less tempted by rococo abstraction, by a certain solemn stance that art should only be impersonal, remote, highly difficult to swallow and slow to digest. Rather, they’re more fascinated in responding to—and mimicking—the instantaneity of our ad-speak, CNN-missing-plane-coverage, death-by-hashtagging celebrity culture. Stylistically, a kind of crystalline limpidity and legibility floods the page. There isn’t a single sentence in E! Entertainment that will cause you to run to the dictionary or force you to reread it backwards and forwards like Howe or Crane, to say nothing of imponderable Ezra. This is something of a vertiginous experience for a reader of my predilections, one trained like a junkie itching for his fix, trained to intuit “poetry” among resistant, complex, polysemous wordplay. And yet what one kind of new conceptual literature claims is that those same energies will be aroused not so much by what’s present within the text but by sensing the invisible contexts which surround it, questions raised by choices of treatment and presentation. There are near-infinite pedigrees of boredom when confronting radical art: the boredom one enjoys, the boredom one admires from afar, the boredom one scoffs at, the boredom one dismisses, the boredom one grows to love and feels entirely changed by. Each has its appropriate worth, I find in time—even the scoffing and dismissive kind. Yet Channel 2, “The Girls Next Door” is a surprisingly traditional literary reading experience. Durbin’s prose-poem-like chunks of block-text offer a relish reminiscent of Mallarmé (who let us not forget anonymously penned countless fashion articles) due to a type of lavish escritoire flavor, complete with its meticulous trills and superfluous description:

The Gothic Tudor-style mansion is tucked away on six acres that enclose a greenhouse, game house, guesthouse, zoo, tennis courts, and swimming pool. The flamingos, peacocks, African cranes, macaws, monkeys, rabbits, llamas and dogs milling blissfully about add a rainbow hue to the otherwise green-dominated color scheme. There are many intimate paths that wind their way around this expensive Eden, with nooks for hidden rendezvous. The wide lawns are spacious enough for vast tents suitable for hosting parties such as a Midsummer Nights’ Dream lingerie gala. There are several sloping hills idyllic for topless slip n’ sliding in the summer or sledding over a gleaming expanse of imported snow in the winter. A marble panel is viewable just inside the video monitored main gate, presenting a description of Aurora, Roman goddess of sunrise, guiding a group of young Eves into the southern California dawn.

This is just lovely. The pleasure in attention here is like reading the Elizabeth Bishop of the Netflix generation, a similar catalogue mania of objects and animals, the wry yet accurate preposterousness of Shakespeare grinding up against ladies undergarments, the hallucinatory OCD in describing something so intricately the reader no longer knows (nor cares to know) the difference between what has been mischievously reimagined versus what’s just being seen as it is. This channel and the one on Amanda Knox are the most writerly, which is to say most readily enjoyable to read and get lost in. This is thanks to Durbin’s considerable gifts as a visually attentive writer. The first and last chapter/channel re-present familiar reality TV stars, transcribing their dialogue with X-acto carefulness, along with narrative assistance that is mostly flat and reads like directives embedded inside a screenplay: “The car’s top is down,” “She turns, hair swishing,” “She shakes her head,” “She shrugs slouched shoulders. She smiles.” Well, of course, this type of writing is deliberately less mesmerizing, a far less literary boredom compared to the above. It’s here where Durbin inevitably asks us to consider the difference between passively watching something that was fun and junky and having to actively read something that is—in comparison—now dry and junky. The utterly sober clarity of the task becomes near religious, an ascetic’s ritual. Even so, like most TV, one doesn’t need to read all of it to grab the gist of it. And even if I personally have no pressing need to devour such a text whole, I can say I’m somehow happy, and relieved, that by this one writer’s obsessive ingenuity it’s been shaped into literature, reality television care of Balzac.

“Entertainment”—what a loaded yet lethally neutral American word for our hyper and inert culture, our perilous and invincible market-economies, our policed and irrepressible identity politics. Kate Durbin has worked to reveal, and slyly concoct, the scripts we’re all viewing but never bothering to slow down and carefully attend to. To her credit, she offers no visible condemnation, no mindless ironic embrace. In short, no answers, rather as many questions as you do, or don’t, want before you switch to the next stream. The world exists to end up in a book, said Mallarmé. UPDATE 3:08 pm PT: Lindsay posted bail and has left the courthouse, said Kate Durbin. Happy viewing!

✖