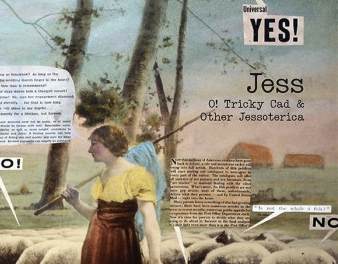

Jess: O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica • Siglio Press • 2013

Jess: To and From the Printed Page • iCI • 2007

The collage artist known simply as Jess is now receiving a welcomed surge of interest, in part thanks to the recent Siglio volume and current exhibition at Tibor de Nagy Gallery. The longtime partner of Robert Duncan, Jess produced work that reads in some ways as the Bay area’s answer to New York City’s Joe Brainard—though I admit to finding the former’s collages, in their newness to me, to have more wit and mystery, thought not nearly as funny or vulnerable. Both artists were embroiled in thriving midcentury poetry scenes, collaborating with and making love to poets, making covers and postcards, manipulating text and graphic. Brainard’s nonchalance, his enviable lightness of touch, is perhaps nowhere more evident than in his Nancy drawings and exact-o-knife flower collages. Jess, in his pamphlets and word collages, his Trick Dacy and Nance comic strips, seems maniacal and baroque by comparison.

In Jess: O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica, lavishly produced by Siglio and cleanly edited by Michael Duncan, the presiding masters appear to be Max Ernst and Joseph Cornell. The same spirit of diabolical obsessiveness and noisy mystery prevails in image after image of Victoriana defaced and split: statuary and classicist portraits, maids and farm animals, goddesses and sphinxes, drawing rooms and dangling monocles. Added to this turn of the century mélange of British decadence and Pre-Raphaelite orgies, is something peculiarly and wonderfully contemporary in feel, Jess’s all-American homosexuality. It’s a type of pornographic play that none of the collage artists I’ve mentioned really engage explicitly—and I for one find Jess’s results riveting, at home as they are in the age Tumblr Eros.

In John Ashbery’s pithy one-page introduction to Jess: To and From the Printed Page (iCI, 2007), you get a charming contextualization of the artist’s work within the history of comic strips and Little Nemo, anecdotes about Picasso and Stein reading the Sunday funny papers as sources to revolutionize their art, as well as a sense of Jess’s—like Ashbery’s—over-the-top oneirism. And yet, the reader might dance upon this surface of reference and not really be made at all aware of the lusty temperature pervading the work. This is partly, I think, due to Ashbery’s preference to never emphasize an artist’s sexuality as grounds for special interest. Don’t get me wrong—I’m not trying to make the case that Jess is a Big Ol’ Homo in comparison to the quieter, more reticent whimsy of Ashbery and Brainard, but there is a pronounced difference between them. Interestingly, Ashbery’s own collages—recently shown at Tibor de Nagy as well—strike me now to exist in the wake of Jess’s vocabulary and syntax as a collagist even though they were contemporaries, Ashbery collaging as a hobby since his Harvard days in the mid-forties.

The sublime libido of twentieth century artistic practice had more than a few great climaxes, but surely one was the radical fracturing of perspective by Picasso and Braque, another the unmediated ejaculation of paint onto canvas care of Pollock. But between these dominant disruptions, artists as wildly different from one another as Duchamp and Ernst found ways to appropriate cubism’s frenetic energy into more subtle, perhaps more disturbing, erotic artworks. The child of the readymade and a very literary surrealism, Joseph Cornell’s boxes are obviously not without their own compositional violence, but often I feel Cornell’s work has a Peter Pan quality—somewhat repressed, wistfully sentimental, at times hauntingly asexual. I confess wanting to place Joe Brainard’s vim and Ashbery’s delicacy (as collagist, not as poet), contagious as they both are, in this artistically arrested latency stage.

I’m sure many would think to lump Jess there as well. But Jess has revealing range. Siglio, one of my absolute favorite presses, shows the artist’s work not to be a one-note novelty; the variety in material, medium, and time period is exhilarating to behold on full-page spreads, with deluxe inserts and minimum editorial interference. That said, Jess was nothing if not obsessed with the human body, its angles and silhouettes, its torsos and appendages. The way they clutter and organize pictorial space can remind you of the same menacing contours in Duchamp’s erotic sculptures (vagina wedges, etc.) and de Kooning’s exploded bodies. Even in the enthralling word collages that have very little to no graphic content—namely Untitled (It chanced on a time), 1959, and Open Mouthed But Relaxed (1952)—one has a sense of this artist’s breakneck and breathless carnality, omnivorous. When a Young Lad Dreams of Manhood (c. 1953) is a mischievous send-up of ‘manhood’—Norman Rockwell scenes of family and home with boys’ heads thrust in business men’s crotches, shirtless wrestlers and dancers and movie star hunks adhesively clumped and humped to one another enough to make Ishmael and Queequeg blush. It’s important to remember how queer these images are for their time—a time before “Queer Culture.” And unlike the pulpy underground ephemera of Samuel Steward, these “paste-ups” and “assemblies” (as Jess called them) seem more than once-taboo artifacts of men’s physique magazines and Hollywood wet dreams.

They aren’t the visible record of anything that ever happened, or could happen, so far as I can tell. Instead, their brazenness reminds us what our imagination can only do inside a collage—what no orgy, porno or painting can quite offer. Extending 20th century collage’s greatest techniques and mannerisms, Jess is the unlikely collision of print culture and poetry, Victorian and mid-century American esoterica, mainstream advertising and underground smut. Superlatives might not matter for much to categorize artwork that actually grants us access to such tangible carnage and imaginary pleasure, but Jess is a great artist.

✖