One of the most difficult poetic devices to teach college freshmen is apostrophe. It all starts out well enough: I get excited to teach an older but inspiring ode, like Percy Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind.” We begin to close read:

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing

—when the students begin to ask questions. Why is he speaking to the West Wind? What is the point of saying “thou” when you are just describing something that can’t listen or respond? I try to explain that this is the point of apostrophe: to address the absent, the unhearing. But they usually remain unconvinced and alienated, which reflects the common understanding that apostrophes “are found throughout poetry, but they’re less common since the early 20th century.”

Their questions aren’t stupid; apostrophe is a complicated, disorienting device, and much of the time I still don’t understand how it works. If we think of poetry as “utterance overheard,” then apostrophe is a sort of utterance directed at someone/something that could never hear it anyway. This radically changes the poem’s meaning; it can’t communicate to its “intended” audience, so we are left with the echoes of an intentionally failed attempt at meaning. But the thing is, in the 21st century we live in a world where “overhearing” textual utterances is commonplace. And like poetic apostrophes, many of these utterances are never intended to be heard by those they address. That’s right, I’m talking about subtweets.

Now, the subtweet does not always directly address the absent/unlistening twitter user through the use of the second person “you”; it often takes the form of a more general statement of “some people.” There’s some debate as to what exactly it means to subtweet, but the general consensus is that it is to speak to or about a group or individual without @tagging them, thus vastly decreasing the likelihood that they will ever know what was said. In fact, I’m both narrowing the set of examples to those that directly address the absent individual and expanding the definition of “subtweet” to refer to a broad spectrum of digital (non)addresses. I’ll call this the apostrophic subtweet. The apostrophic subtweet would not include the tweet about “some people who don’t respond to texts #smh” but would include the Facebook post addressed “to the man wearing toe shoes in the coffeeshop.”

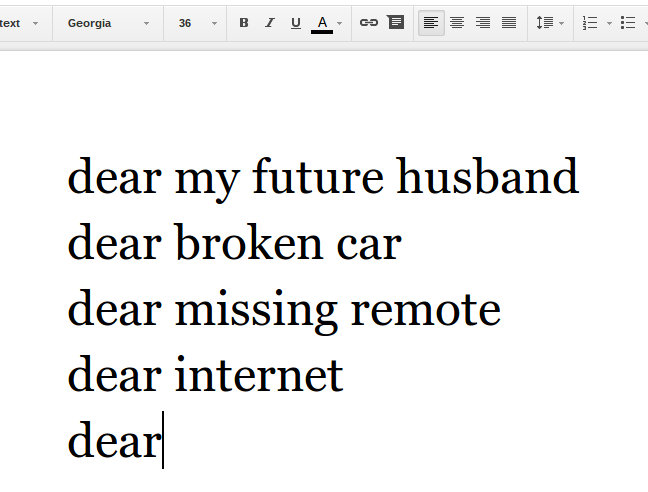

“O” is the common introduction to poetic apostrophe; “dear” is the common introduction to the apostrophic subtweet. A quick search of twitter reveals thousands of examples addressing unlistening people, companies, and organizations. As my friend Elizabeth has described it, this phenomenon often reflects a snide, passive-aggressive sort of performativity. “To the car that cut me off on my way to work,” “dear mansplaining auto-mechanic”: these are ways of venting frustration without fear of dialogue or interaction. These subtweets take the anonymous “thanks for double-parking asshole” note to the next level; not only will they never respond, but they will never know. And while I can often relate to these expressions—I mumble curses to deal with the irritants of modern life—I am unsure why one would want spread this kind of discourse digitally. The critical subtweet often takes the negative energy of everyday life and displaces it onto an unsuspecting audience, either in an attempt to evoke outrage or sympathy. There is power in spreading some versions of this negativity (see the apostrophes used in #yesallwomen), but most of these subtweets of the mundane are the scourge of the internet.

Yes, the apostrophic subtweet is often critical, but not always. Take, for example, the truly strange twitter account @FutureHusbandmy. This account supplies an endless and constant supply of tweets to an imaginary/absent “future husband” who doesn’t (yet) exist. The tweets range from the wryly clever (“Dear my future husband, please don’t judge my obsession with dr. pepper”) to the hopeful (“Dear my future husband, we will be that old couple that people see and can clearly tell we are still madly in love with each other”) to the pitifully heartbreaking (“Dear my future husband, our wedding does not have to be this huge ordeal. I just want a wedding that makes you my husband,”) all within the course of a day. This account is tragic and baffling and narratively powerful all because of the pathos of the apostrophic subtweet. Here and in other subtweets of praise, the absence (or nonexistence) of the listener/reader becomes the primary effect of the address. These recall odes to the deceased (and many are) in that they are powerful precisely because they go unheard.

Apostrophic subtweets are not only limited to addressing people, either. In addition to companies or organizations, the inhuman is also often the object of the apostrophic subtweet. These unhearing entities are often those things that can cause intense irritation (broken cars, missing remotes, wireless routers) or affection (mostly pets). But I have noticed a growing trend towards addressing the abstract; “dear internet” can function either as a metonymy for a digital audience or an apostrophe to an idea. This sort of abstract apostrophic subtweet works because it uses language to engage that which engages us in other ways. The excellent television blog “Dear Television” on the Los Angeles Review of Books does just that; in addressing the medium, the authors allow us to see a relationship and an attitude. This is the apostrophic subtweet at its most abstract, its most poetic; here we are in the realm of Shelley’s West Wind.

In a way, apostrophe is the most relevant poetic trope of the digital age. As we become more and more surrounded by language both real and virtual, we develop a familiarity with texts meant for other eyes and ears. And though communication is now nearly instantaneous, nearly free, we realize that direct address is not always optimal, not always possible. We need more ways of expressing ourselves, of juggling audiences that are vast and inconsistent, omnipresent and unlistening. The apostrophic subtweet is a powerful tool in this arsenal, to be used for good or ill.