These Upworthy Titles Will Restore Your Faith in Humanity. But You Won’t Believe What Happens Next.

Clickbait is bad. Clickbait is ruining journalism. Everyone knows this. Everyone hates the formulaic success that BuzzFeed has generated with endless listicles about animals, the 90s, and animals in the 90s. Upworthy inspires a slightly more complex disdain: it claims to engage in advocacy by “raising awareness” through viral videos about “issues” instead of cats and the quizzes. Most of the more political friends I know HATE this “clicktivism,” since it gives “readers” a sense of political involvement because they watched a video about a kid who stood up to bullies. And traditional media don’t seem too happy with Upworthy either; responses range from indignation to smirking analysis to truly depressing defeatism.

An interesting thing about these complaints, besides the fact that they all read a little like Business Insider articles, is that they all address, even focus on, the titles of the clickbait articles. And I suppose that is the defining characteristic of clickbait as a genre: titles that manipulate or coerce readers into visiting the site. They are infinitely imitable: a clever website even parodies the style of clickbait title creation. But what do these titles mean? How do they work? Whatever loathing I feel for listicles and viral videos and their effects on my time and attention span, I actually appreciate, even enjoy, the way they imbue their titles with such mystery and suspense. So…

I Am Here to Take Back the Clickbait. In Three Simple Steps, Find Out How Upworthy Titles Create Cognitive Problems In Readers. But What Happens If You Don’t Click? You Won’t Believe What Happens Next.

✖

Upworthy Titles Often Make a Relatively Banal Claim. Until They Change It.

The most essential grammatical tic that Upworthy employs is a bit more complex than simple word choice or sentence structure: the titles introduce a fairly typical story, idea, or theme in the first sentence, then use a much shorter sentence to complicate or undermine it. This is irritating as hell. And I think that’s the point; the second sentence piques you to resolve the irritation it causes.

A quick perusal of today’s Upworthy page shows sundry examples of this construction, which range from the accusatory:

There’s A World War Happening Online Right Now. And You Might Be A Mercenary In It.

to the empowering:

If You Could Press A Button And Murder Every Mosquito, Would You? Because That’s Kinda Possible.

to the defensive:

A Guy Talks About Rape From A Man’s Perspective. (And It’s Not What You Think, Either.)

to the cryptic:

This Story Starts Out So American, Normal, And Everyday. Until The End.

The key element in these titles is the relationship between the first sentence and the second. The first is relatively traditional, while the second sentence is short, annoyingly informal, and conspiratorial. We might call these couplets epodal because of the relative line lengths, but I think the effect is more similar to catalexis in that the second line’s brevity emphasizes something unfinished or incomplete. The second sentence is intentionally vague: click here to finish the thought, answer the question, solve the riddle! And, like most unfinished stories, the conclusion is rarely satisfying. But as someone who rarely clicks on Upworthy links, I have come to appreciate the beauty of these teases. Read the above titles again, but without registering the hyperlink: now they read like Buddhist koans. You want to know how you might be a war mercenary, but can you know, really? Bask in the not-knowing.

✖

Upworthy Has Helped Restore Our Faith in Humanity.

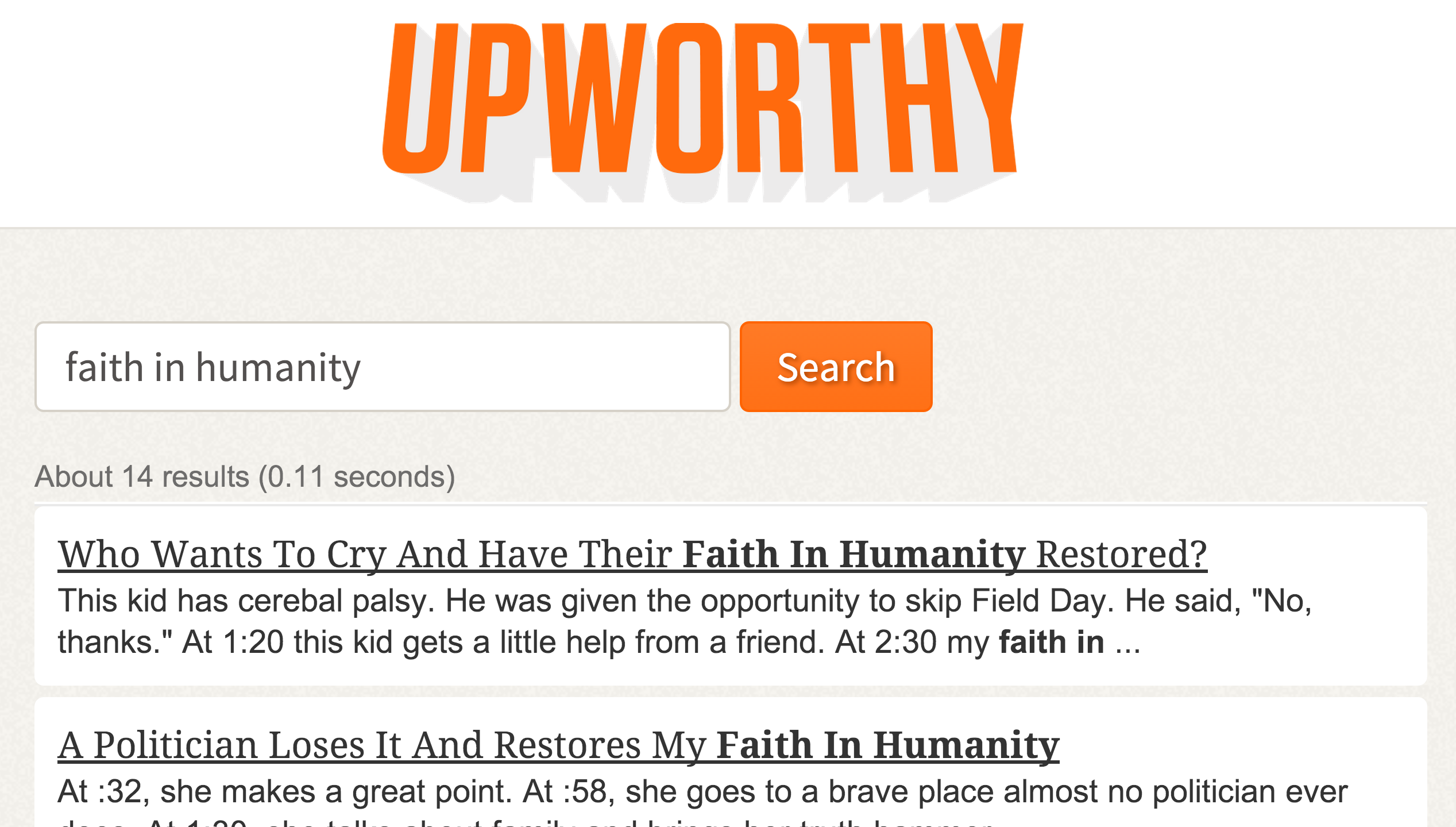

A quick search of the Upworthy site will reveal hundreds of great examples of the phrase “faith in humanity.” Anecdotally, I don’t remember this phrase being used much before the Rise Of Clickbait in the last five years. But is this something connected specifically to Upworthy, or is it just evocative of clickbait in general? Let’s look at the internet search frequency. Check out the graph:

What happened in 2012? Upworthy launched.

A quick tangent: I have a fun game/exercise that I play with my rhetoric classes. I pick a seemingly innocuous phrase that is (over-)used in mass media, then I ask the class to explain what it means. No matter what they say, I either pretend not to understand, or ask “no, but what does it mean?” The students think it’s frustrating, then funny, then, frustrating again. A favorite phrase for this game is “senseless violence.”

The point of the exercise is to examine some of the contradictions or confusion we use in everyday language. I feel this way about the phrase “faith in humanity,” and especially “restore [my/your/anyone’s] faith in humanity.” What is humanity, what does it mean to have faith in it, and why does the faith need to be restored? I assume that humanity means something close to “the goodness of human nature,” and not “the essential or unifying nature of personhood,” but I’m really not sure. At the very least the repeated recycling of this phrase should serve as a reminder of the Sisyphean task of restoring faith in humanity, whatever it may mean. Humanity is always already in doubt; our faith must endlessly be restored.

✖

You Won’t Believe What Happens Next.

I can only assume that the phrase “You Won’t Believe What Happens Next” is meant to be ironic and conversational. That is, the next event or revelation is so surprising as almost to inspire disbelief, but is actually real and to be believed. But the repetition of this clause only fills me with some vague Lovecraftian dread for the future. After all, the sentence has two elements: “you won’t believe” (disbelief, incredulity) and “what happens next” (anticipation, the future). The combination creates a tension in me that can border on the existential. These phrases are used and reused separately too, and the results can be pretty disturbing if you stop to think about them. Some examples:

These Women Once Wanted To Shed Their Skin; You Won’t Believe Their Reasoning.

These Workers Just Want Money, And You Won’t Believe What They Did To Get Some.

A Gorgeous Waitress Gets Harassed By Some Jerk. Watch What Happens Next.

Someone Gave Some Kids Some Scissors. Here’s What Happened Next.

It’s also worth noting that this is the second Upworthy #trend (#upworthytrend?) that focuses on (dis)belief. Is Upworthy indirectly addressing a crisis of faith that internet users collectively feel? Is there something about the hyperlink that makes us want to believe, or disbelieve, what is on the other side? Does clickbait restore our faith or inspire our disbelief? These are the things I think about when high school classmates and family friends post or tweet Upworthy links. In my experience, this is much more rewarding than clicking through.