I consider myself a modern man about the internet, but that doesn’t mean I support or enjoy all developments in the realm of net-linguistics. For example, I positively loathe the 2013 word of the year, “selfie.” To me, its popularity shows the internet’s obsession with self-referentiality and pride; its use is usually both self-aware, tongue-in-cheek, and at the same time completely earnest in its boring self-representation. But I don’t want to talk about the things that I hate about language these days. Instead I want to look at ways that the internet has learned to negotiate Web 2.0’s commentsphere, which demands interaction and response to the constant cultural phenomena streaming across our smartphones and laptops.

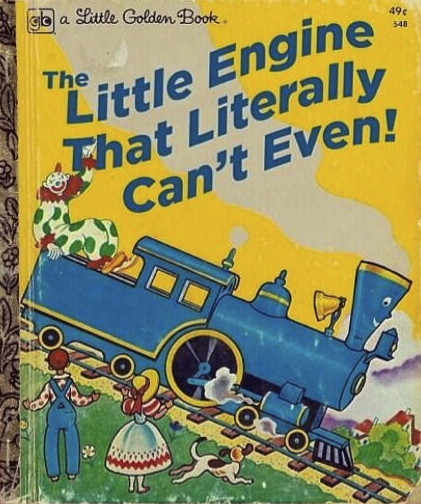

In short: I can’t even.

“I can’t even,” along with its object-taking iteration “I can’t with___,” has been an internet expression since around 2005. That’s almost a decade, but in the past year awareness of the slang has spread to squarer circles. By this I mean grown-ups who write articles. Some people hate “I can’t even” because the construction is hasty and inarticulate (“I implore you to slow down and speak with enough declaration so that your thoughts are complete and not just recurring fragments”). Others defend it as “allow[ing] us to subvert standard grammar constructions and experiment with changing verbs to nouns and vice versa.” In general, most of the responses or analyses I’ve read have the same “kids-these-days” attitude that all articles about netspeak have, which makes me wonder if most critics make distinctions between different developments at all.

I am also both heartened (other people think about these things!) and disappointed (beat to the punch!) to find out that Rebecca Cohen already identified this as an example of aposepesis in Slate. Yes, trailing off when excited or overwhelmed is something that Virgil did, Shakespeare did, the Three Stooges did. I’m pretty sure that our parents and grandparents didn’t complain when Ralph Kramden didn’t finish his fantasies of domestic violence when he exclaimed “One of these days….” Although maybe they should have; the misogyny in that show is astonishing.

But I’m not here to argue for the historical continuity of “I can’t even.” I’m here to look at its broken, suggestive grammar, and to try to understand why and how our culture finds a way to can’t.

To begin: “I can’t even.”

There’s a lot going on with “can” in this construction. It’s a modal verb, like “must” and “should,” which means that it describes the relationship of a subject to another verb. When “can” or any modal verb is used without a contextual referent, it becomes virtually meaningless. Doesn’t that verb look lonely in that diagram without anything following it in the predicate? This means that walking up to a stranger and saying “I can” or “I must” means even less to them than walking up and saying “I bike.” Trust me, I checked.

This is important because it shows that “I can’t even” is always a response to an implied question or demand. Yes, it might not make sense out of context, but is there ever no context? Listeners often assume the implied verbs to be “to handle,” “to deal,” or “to cope,” which all would explain the overload of excitement or disgust that could evoke such sudden inability. But the phrase works so well because it implies all of these, as well as comment, respond, or anything else you need it to. “Can” is also a fluid modal verb that often implies willingness as well as ability. To can’t even might (also) mean to won’t. With “I can’t even” we thus have a fluid modal verb that implies an ambiguous relationship to an unknown primary verb. And yet everyone on the internet understands what the speaker means in relation to the context, whether it is a heroic cat or a Knowles elevator fight. On the internet we are united in our inability to can.

As for even: what does it even mean? Language Log nailed it a few years ago, so I don’t feel the need to go into it extensively. But I want to point out that in our case the even is more acute because of the vagueness of the verb. Language Log notes that even often works by “intimating … an extreme case of a more general proposition,” but what does that mean when the proposition is so general as to border on meaninglessness? The inability to can is more intense and demands your attention, even as it refuses to explain itself. I can’t so much I can’t explain.

And one quick look at “I can’t with ___”:

I used “basic bitches” because it comes from my favorite reaction gif on the internet; modern uses of the word “basic” deserve a column to themselves. But notice how the preposition hangs off of this truncated verb: I can’t what with you basic bitches? This is, in a way, the point: you’re too basic to know. The “with” provides a direction for the “can’t,” but doesn’t define a relationship. To can’t with is simultaneously to acknowledge and to defy.

But the most essential element of “I can’t even” constructions is sneaky: that little “‘t.” What is the difference between “I can even” and “I can’t even”? A lot. Old folks and critics might say that the difference is one of attitude, that “I can’t even” says something about millennial defeatism. Well, “I can’t even” is a statement of attitude, but it’s one of defiance rather than pessimism. In a world more and more filled with breaking stories, shocking video, and viral outrage, it is becoming necessary to can’t even. In this way “I can’t even” is a philosophical expression: the economy of attention, emotion, and time has overloaded, and I assert my right to can’t. I would like to think that a 21st century Bartleby the Scrivener would trade in his politic but outdated “I would prefer not to” for the casual dismissiveness of “I can’t even.” “I can’t even” is an expression of negation, but a vague one; it answers the call of any situation, the call any media, with a “no comment,” while also refusing apathy and total disengagement. It is always relevant because we are always being asked to can even.

✖