Edith Wharton anticipates Kim Kardashian

One hundred years ago, in 1913, Edith Wharton wrote a novel called The Custom of the Country. The country is America; the custom is divorce. And the first line is: “‘Undine Spragg—how can you?’ her mother wailed.”

I imagine the question “How can you?” delivered with inflections of astonishment. In both her mother’s opinion, and her author’s, Undine gets away with things other people just can’t. Throughout the book Wharton questions Undine: How can you be so superficial? How can you be so self-involved? How can you be so heartless? How can you marry and divorce so easily?

Undine can, and does; in part because she is so beautiful. Wharton both condemns her character’s choices, and envies them. Not only is her heroine fiction, she is fantasy. Best-selling fantasy. Undine tapped into the desires of women across America. At that time fiction was serialized just as TV is today and the American audience was hooked. “Undine is making the press ring,” Wharton boasted. Note she did not say: “Custom is making the press ring!” Wharton recognized the novel is defined by its heroine.

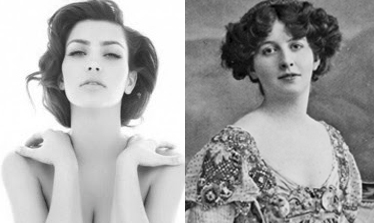

Although most Americans are no longer reading Custom, we’re still hooked on the personality cult Undine represented. The beautiful, independent, selfish woman who continues to be redefined by each generation. I would argue today’s incarnation is Kim Kardashian.

“Kim Kardashian was photographed grocery shopping” sums up the reality TV star’s fame. Americans cannot get enough of Kim, and she is photographed or filmed doing everything. On her family’s reality TV show—Keeping Up With the Kardashians—you can watch her shop, eat, email, drive and date. Most recently, marry and divorce.

Like Kim, Undine Spragg’s job is being beautiful. She is “stunning” and “too lovely.” Her name even ties her to the beauty industry at its most prosaic. She is named after a hair-waver her father “put on the market the week she was born” which is a reminder of her humble origins as she begins her social climb.

At the beginning of the novel, her nouveau riche parents have moved Undine from Apex, the Midwestern town she grew up in, to a hotel in New York City. She spends her days shopping and gossiping with her mother’s manicurist, reading tabloids, and pining to know the people she reads about. Her great break, socially speaking, comes when she meets two men in the hotel lobby. (That’s still happening: in 2003 R. Kelly sings “after the party it’s the hotel lobby” in his hit “Ignition (Remix)”.) One of the men is from a patrician New York family; the other is a society portrait painter. They both take an interest in Undine, presumably because of her looks. After a brief courtship she marries Ralph, the patrician one. It’s only the beginning of Undine’s romantic career: she goes on to have an affair, marry a French Count, divorce him and finally, marry a millionaire.

✖

DIVORCE

The American institution of marriage changed dramatically in Wharton’s lifetime. In her biography of Wharton, Hermione Lee points out that divorce rates in the US doubled between 1880 and 1900 and by 1920 had more than doubled again. This was due to new laws in western states like the Dakotas. And if you lived in a state with stricter laws, like New York, you could go out west to get a divorce, which is exactly what Undine does.

Wharton was intimately familiar with the subject; she had divorced her mentally ill husband in a painful and drawn-out process (Lee writes that his symptoms indicate bipolar disorder or manic depression).

Edith Wharton was not well-suited to be Teddy’s wife and caretaker; she was both sexually and intellectually frustrated by the role. She was independently wealthy—with money from both her family and her books—and her social circle was wide, extending across America and Europe. She was brilliant, aesthetic, and energetic. If any woman was in a position to divorce, it would have been her. But she was tortured by the decision.

There are no happy marriages in Wharton’s novels, but her personal letters show an abiding belief in the possibility. She writes to her niece, “Fasten with all your might on the inestimable treasure of your liking for each other and your understanding of each other…times come when one would give anything in the world for a reason like that for living on.”

Undine’s attitude is the opposite of Wharton’s. She is concerned with the visual and not the verbal. She doesn’t seek to understand, she always wants to move on. She embraces the new; she embraces change. Change in husbands seems as natural to her as change in fashion. She is never idealistic about marriage. She states her opinion of divorce at the beginning of the novel and sticks to it: “Out in Apex, if a girl marries a man who don’t come up to what she expected, people consider it’s to her credit to want to change.” Her point of view is precocious, anticipating America’s no-fault divorce laws—which only became legal in all fifty states in 2010.

Undine voices the vague discontent that is symptomatic of American dating culture today—the attitude “he’s not good enough,” or “she could do better” and “something is missing,” and “I just don’t think he’s The One.” This is Kim Kardashian’s dialect. Since filing for divorce from Kris Humphries each episode of their televised wedding show—Kim’s Fairytale Wedding— starts with this statement, a sobering white message on a black screen:

“After careful consideration,

I have decided to end my marriage.

I hope everyone understands this was not an easy decision.

I had hoped this marriage was forever

But sometimes things don’t work as planned.

We remain friends and wish each other the best.”

Kim Kardashian

She gives no legal reason for divorce and no emotional one. Her husband isn’t even mentioned by name. The decision is portrayed as entirely one sided, “my marriage,” Kim says possessively. A few lines later, “this marriage” implies that there will be others; like Undine, she is ready to embrace change.

Divorce is not anti-marriage to either woman. It facilitates more marriage: it is the pre-requisite for the next, better match. Undine says “I know just what I could do if I were free. I could marry the right man.” This opinion might not be new to the emotional vocabulary of married women, but it was radical to state it so bluntly in 1913.

For beautiful women, there is usually another man. Both Undine and Kim attract almost universal male attention, and consequently individual attention matters very little. Men become interchangeable. In Episode 2 of her Fairytale Wedding, Kim says to Kris, “Babe I seriously have been planning this dream wedding since I was ten years old like it’s such a girl thing.” Kris’s reply is heartbreaking and—perhaps accidentally—astute: “Yeah then you could just slot any guy into it.”

✖

SEX

It is a great American myth that beautiful people have better sex; Undine and Kim don’t.

Kim’s romantic life has been public since 2006 when a sex tape she made with her boyfriend became an internet phenomenon. Kim’s next romantic video was much tamer: In 2011 Kim’s Fairytale Wedding aired. Within a month of the show’s release, Kim had filed for a divorce from basketball player Kris Humphries and began dating the rapper Kanye West, who she had met partying years earlier. Kanye announced Kim was pregnant by stopping a recent concert and asking the audience to “give it up” for his “baby mama.” They cheered. And then presumably, a lot of them went home and watched Kim Kardashian porn.

At both her marriage to Kris and at Kanye’s announcement of her pregnancy, internet views of the sex tape “Kim K. Superstar” spiked according to TMZ.com. If you watch the tape, you will see she is an unconvincing sexual partner. She chews gum, keeps her bra on, and, although she claims otherwise, never registers physical signs of orgasm. For anyone who believes in mutually pleasurable, uninhibited sex—it is a very sad video.

“Kim K. Superstar” then is an ironic title. But this irony is completely lost on an audience who is getting off either because they think this sort of sex is hot, or because they like to see Kim humiliated. As it should be, we don’t go to pornography for irony.

Undine’s earliest interactions with men are also sexual. Before she leaves Apex she is engaged to one man and then secretly married to another. When she comes to New York she immediately gets involved with a riding instructor who she thinks is European aristocracy (she breaks it off when she realizes he is not). Her attitude towards sex is permissive, which is increasingly shocking as she climbs the social ladder towards Puritan and Catholic heights. But despite her experience she is also disinterested. “Cool” is the word Wharton most frequently uses to describe Undine’s reactions to men.

After her marriage to Ralph, Undine even approaches adultery cool-y. The first time she cheats on her husband—she kissed Peter van Degen. This kiss has the potential for great emotional and social trauma, but she is underwhelmed: “Her physical reactions were never very acute she always vaguely wondered why people made ‘such a fuss,’ were so violently for or against such demonstrations. A cool spirit within her seemed to watch over and regulate her sensations, and leave her capable of measuring the intensity of those she provoked.”

Undine’s lack of passion enables her to be more calculating in her romantic life. Peter van Degen has an affair with Undine because he wants sex; Undine has an affair with him because she wants to spend money, to be given jewelry, to be chauffeured around New York, and to be sailed around Europe. She wants a sort of commercial citizenship of the world, usually denied women. She wants the freedom of being rich, and independence from the household demands of a husband and child; Wharton doesn’t exactly blame her. But she also doesn’t give Undine what she wants, yet.

When Peter learns Undine has been partying with him in Europe while her husband Ralph is mortally ill in New York, he leaves her. In his only demonstration of imagination, Peter thinks that if he married her she might treat him like that, too, and leave him for someone else.

✖

PRICE

Poor Ralph. When he marries Undine, he “fancied that his own warmth would call forth a response from his wife, who had been so quick to learn the forms of worldly intercourse.” But Undine doesn’t want to learn. Love, for her, is a form of worldly intercourse. It is in the same dimension of life as shopping, travelling and parties. And can you blame her? She doesn’t think—or dream—in any other sphere.

Ralph doesn’t learn either. He can’t stop believing in the love he learned from reading fiction and poetry and looking at art. He can’t relate to Undine’s material understanding of love. He can’t learn to love clothes any more than she can learn to love poetry.

In every role of lover or beloved—as daughter, wife, mistress, and mother—Undine is unrelentingly material. She is devastated to learn she is pregnant because she can’t bear the idea of not being able to fit into the fall clothes she bought in Paris. While Paul is still a child she leaves him and Ralph to go live in Europe. When she does think of Paul, it is again in relationship to clothes: “it was dreadful that her little boy should be growing up far away from her, perhaps dressed in clothes she would have hated.” She leaves Ralph and Paul, and then decides she wants her son back, because she thinks he might make her more attractive to the conservative aristocratic family she wants to marry into. Pragmatically, she puts a price on his head: she tells Ralph he can buy his son’s custody for $100,000.

When Ralph realizes he can’t raise the money to keep his son he commits suicide. He cannot imagine his life without his wife and son, without love. He knows his love for Undine is unreciprocated, but he can’t help loving her. He knows his suicide will give her what she wants: Her freedom, her son, unrestricted access to his money; and he gives it to her. Wharton writes his final thoughts:

‘My wife…this will make it all right for her…’ and a last flash of irony twitched

through him. Then he felt again, more deliberately, for the spot he wanted, and

put the muzzle of his revolver against it.

It is eerie, for a fictional character to call out the dramatic irony of his situation so bluntly.

Undine also expresses a vague sense of unease at Ralph’s death, as if she too senses that all is not right in the land of fiction:

His death had released her, had given her what she wanted; yet she could honestly say to herself that she had not wanted him to die—at least not to die like that…even since her remarriage, and the lapse of a year, she continued to wish that she could have got what she wanted without having had to pay that particular price for it.

The dramatic irony is clear here, too. The reader knows that the price was too high, that Undine did not just leave Ralph but essentially murdered him. But we are not entirely on Ralph’s side—he is as uncompromisingly romantic as Undine is mercenary. His death is tragic, ironic, and a bit pathetic.

Typically, Undine quickly recovers from her brush with reality. Now a respectable widow, she is able to marry the Catholic aristocrat who has fallen in love with her and enjoy her new life as a French Countess. Wharton does not punish Undine in the plot; at the end of the day, Undine is still getting what she wants, and still wanting more. Undine has not changed. But there is a chance that the reader has.

Remember how Wharton described the potential for her niece’s marriage: “the inestimable treasure of your liking for each other and your understanding of each other.” Wharton never had that in her own marriage. But I imagine she seeks that combination of “liking…and understanding” from her readers.

Quoted out of context, Undine seems pretty disagreeable. But she is a hilarious and often delightful character to read. And whether or not the reader likes her, she entertains. She is vivid on the page. Wharton’s prose entertains, too. This question of liking is not personal to either Wharton or Undine. It has to do with the intangible appeal of the fiction; its success at creating a world. The best gauge of this is Wharton’s popularity; she was a bestselling writer.

Understanding is more complicated than liking; it does not have to do with popularity. In fact, I would argue it is inherently unpopular, this effort to understand life through fiction. We are on unsure footing as to the author’s intent. But it doesn’t really matter, irony and ambivalence have ushered us into the realm of interpretation. This is the sort of active reading that can change the reader’s mind: about the world around them, and their place in it.

So what if we stop reading, and start watching reality TV?

Reality TV is a hyper earnest genre, and the Kardashians are a very literal family. Khloe says in Episode 1 that Kim is a “beautiful trophy wife who has a ton of money and works her ass off, great personality.”

Kim is a winner; reality TV is for winners. Kris Humphries will not get his own show. Like Ralph, he disappears. And the Kardashians, the family that talks about everything, do not even mention his name. We are only given Kim’s statement, “I hope everyone understands.”

She moves on to the next man—and the audience follows, or disappears. There is no room for ambivalence. There is just a purgatory of like and dislike; we can like to dislike her, we can dislike to like her—but even this level is relatively simple. It is the same: we can judge Kim. The game doesn’t change, neither do we. There is no chance for understanding, no one to ask: “How can you?” Which to my mind shows a deep disconnect with reality.

✖