I grew up in a country where writers were like rock stars. It was the 90s: Norman Mailer-era America was over, had moved on to other things—but in France, you could still see a barely-handsome author on the banner of a newspaper. He’d be standing there, dwarfed by a cardboard rendering of a simply designed book cover (thin red border, block lettering, discrete logo as the belly button of the page).

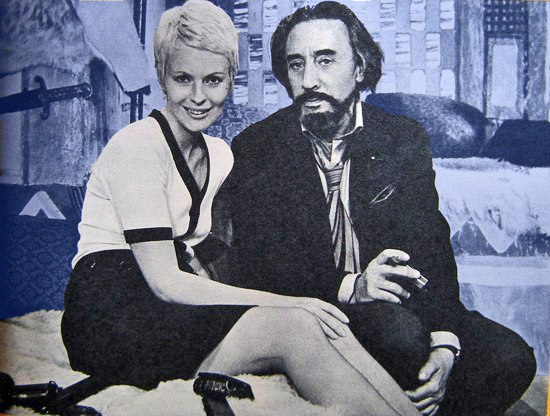

It was during a discussion about American and French reading cultures that I first discovered the multi-hyphenate author-diplomat-aviator Romain Gary. My companion asked if I knew about him during a conversation concerning Jean Seberg, Gary’s second wife. I’d pronounced her name “John Zeberg,” having read it so many times, but never having heard it aloud. He laughed, and I realized my mistake. “JEEN SEE BERG.” (I felt stupid for a second. But I was a reader—I’d met her in a story somewhere, not on television or in the movies, and where I came from, grew up, rather—France—that’s how the name might have been pronounced.)

Gary is the only author to have been awarded the Prix Goncourt twice: once under his own name, and once under a pseudonym. This despite the rules of the Goncourt stipulating that it can only be given to an author a single time; the Academy awarded “Emile Ajar” the prize without knowing his real identity (Gary.)

I think about Gary and his work published under the pseudonym Emile Ajar, and I keep wondering how exactly his path would have played out had it all gone down now, decades later. How would this hoax unfold, in the world of social media?

Gary’s is a great legacy, a good writer who tinkered with the machine of cultural and social perception. If he hadn’t done just that, using the play of media and identity to his advantage, so many people may never have fallen in love with Gros Calin or La vie devant soi. Gary once said (I’m paraphrasing), “We all have identity problems; sometimes you have to regenerate yourself.” Here’s to all that, my ode below:

A modest, comic reinvention:

“My name is Noveila Lloyd and I was born in Greenwich Connecticut on April 17, 1976. My mother was a supermodel with blonde hair and blue eyes. I have neither. I can’t remember what shade of blue her eyes were because she left my father and me when I was young, though it’s unclear exactly when. At the age of fourteen, my father moved us to Canada after I’d been scouted by my mother’s agency in New York. The other half of where I came from expected me to be a successful actress or writer, and nothing like my mother. So, he took me around on odd jobs all over, anywhere except New York City and Connecticut. He didn’t want me to be corrupted. When I was young, this meant he didn’t want me to be me. I wrote all about it in my first book, an effort to prove my intellectual worth. He panned it. Critics liked it. Whatever. “We all have identity problems. Sometimes you have to regenerate yourself.” At twenty-one, I published my first novel and not soon thereafter married a great essayist, the editor of an obscure literary magazine that my father loved. Together, we went to all the dinners and parties in Paris and New York. I grew bored; he suggested I date Bryan Gosling as a distraction. I met the actor when I was having a meeting at WMEA in Los Angeles about my book. It had been a huge success in, of all places, France. The jokes apparently translated better. A commercial hit overseas, they wanted to see what I could do to make it more popular in the English-speaking world. A month earlier, I won the National Book Award. Who cares? Gosling proved more than a distraction and we fell in love and soon I was pregnant. Little Maria went to live in New Zealand with her aunt; we had to make it seem like she was born a year later than she was, in order to keep up appearances.

All the while, I was writing and writing a book about a young female actuary’s relationship with her pet starfish. “We all have identity problems. Sometimes you have to regenerate yourself.” Titled “Hugs xo”, the story was published when Maria turned twelve, though not she or anyone else knew it was by me, her mother, now a washed-up mildly pretty old ingénue. (In the meantime, I’d found out my husband was having an affair with a hot young thing. I challenged her to a bake-off. She declined. We divorced.) Soon an “Emily Ferme” published the book and suddenly New York and Hollywood were electric with praise for the arrival of this new Kiwi talent. She stood out from a landscape of mediocrity populated by has-beens like Noveila Lloyd. Ferme won the Pulitzer for “Hugs xo” which was then turned into one of the highest grossing films of all time. She was also very popular on social media with 3M twitter followers and about the same on Instagram. (I would send my updates to my cousin in New Zealand to post from her computer to make sure it all matched up: coding, location updates, IP addresses, all of that. This was also how we submitted the completed manuscript, making sure to cut and paste it into a Word doc created on her registered desktop.) When it was necessary for Ferme to make public appearances, my cousin flew in. She looked a lot like my mother in her heyday, which made people start to wonder. With Maria grown and my ex-husband lost to Hollywood, I kept writing, and then decided to try my hand as a spy…”

This autobiographical essay was found at the scene of Lloyd’s recent suicide. It was later revealed that before she died, she texted Maria the emojis for “Thank you and Goodbye.”

✖