- Molly Crabapple

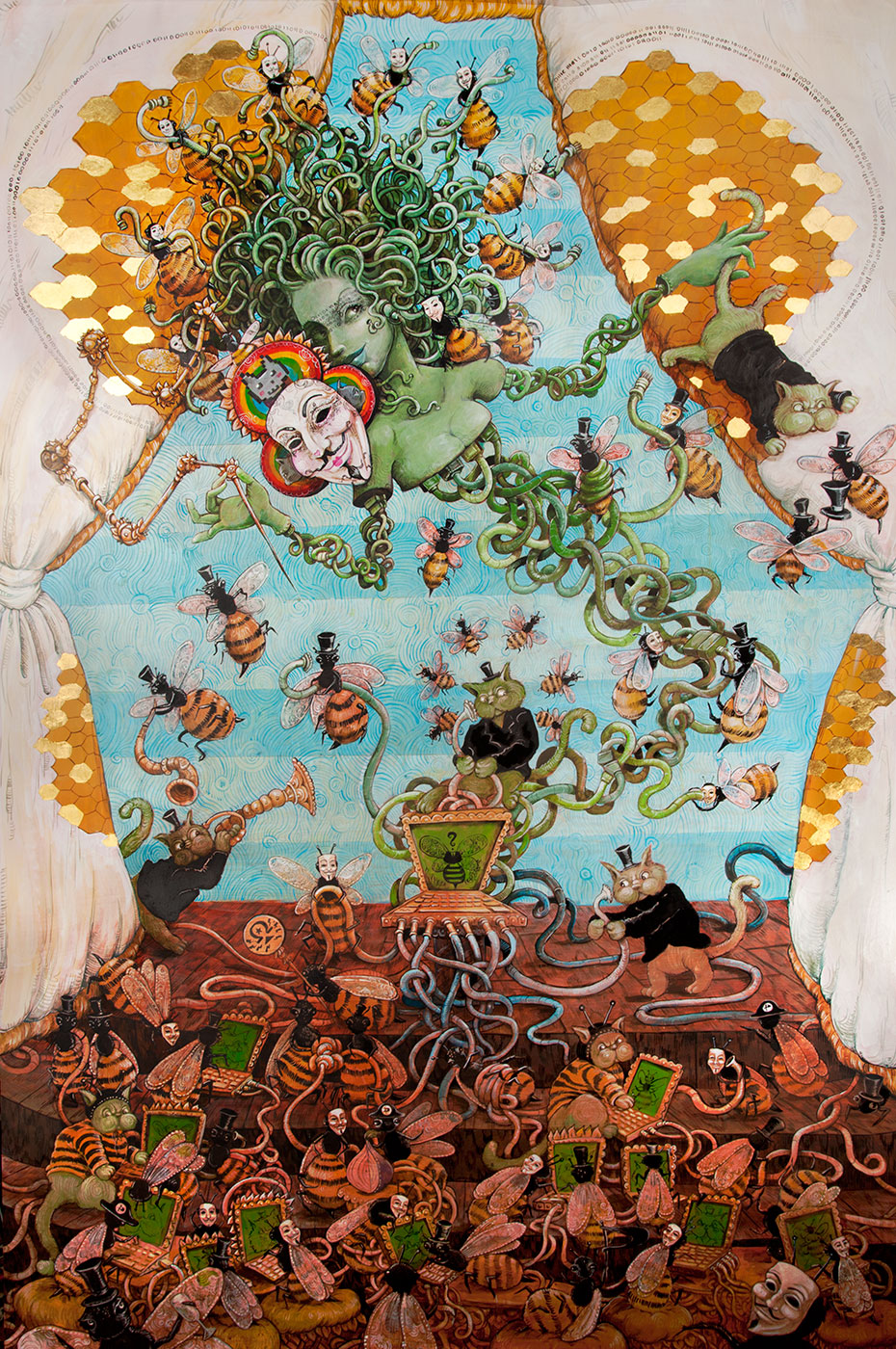

The American Reader asked five questions of artist Molly Crabapple, whose most recent exhibit, Shell Game, opens Sunday April 14th at Smart Clothes Gallery in New York City. Shell Game is comprised of nine 6′x4′ paintings and one 3’x3’ painting that document and interpret the social, political, and financial upheavals of 2011. Chris Hayes has rightly described these works as “bracing, exuberant altarpieces for the revolution.” In the following answers, Ms. Crabapple meditates on the aesthetic dimensions, imperatives, and promises of political crisis.

A selection of her works can be viewed in the slideshow above.

—Uzoamaka Maduka

✖

American Reader: What was most immediate to me, seeing the paintings that comprise Shell Game, was the conversation it took up by virtue of its visual language—that is, the way that language recalls the political cartoons of the Gilded Age and the Tammany Hall era. These paintings seem to be descendants of that aesthetic, and, of course, discuss a similar subject as those cartoons: the orbiting of greed, corruption, and structural treason (i.e. acts that would be considered treasonous if not committed by politically influential agents) around the American ideal, and how that ideal is both undone and constructed by these forces. Do you consider your work to be in conversation with this period of American art? Do you see any important differences or similarities between your work and theirs?

Molly Crabapple: I do! Political cartoons have traditionally been one of the most subversive artforms—the joke that hides a bomb. Thomas Nast helped bring down Tammany Hall. Several years ago, the cartoonist Ali Ferzat’s hands were broken by the Assad regime. It’s art that’s populist and dangerous—that crosses borders between nations and classes. Arthur Szyk’s sprawling anti-Nazi illuminations were also direct inspirations—political cartoons created with the gold and paint we’re more accustomed to seeing in “high” art.

Where my work differs from a political cartoon is that it doesn’t draw conclusions. Nast had a goal—to bring down Boss Tweed. While my political sympathies are obvious, Shell Game is a love letter to a year, not a policy proposal.

AR: This cartoonish quality is of great interest to me, especially because the subjects you deal with are quite grave. Things are disintegrating, but they are often disintegrating into bubbles, balloons; there are villainous actors, but they take the form of mice and cute animals. Of course, one can see this as a distancing mechanism, but I wonder whether you find there to be a profound relationship between cuteness and horror, cartoons and trauma?

MC: When I was in Greece working on Discordia with Laurie, I saw a lot of cops. The Greek cops are mostly Nazis. They vote for the Golden Dawn, Greece’s Neo-Nazi party. They are behind countless human rights abuses. But there they stood on the street corners, in their riot shields and sashes of teargas canisters, their muscles and their armor. They looked like nothing so much as Rob Liefeld characters. So that’s how I drew them. There’s a profound ridiculousness to so many displays of power.

Also, animals are fun to draw.

AR: With one exception, these central figures, these women—who you’ve said represent an ideal—are always smiling, even in their dissolution. One wonders if they are actually disintegrating, or if they are in the process of being constructed via new artifices (the bubbles, balloons). Especially because these women often hold masks. Is the central figure in these paintings the woman, the heroine, the villain, or something else entirely? Do you think the ideal is under siege in this political climate or is “she,” in some way, the siege itself, in masked and marvelous form?

MC: Doing big, time-consuming art based around current events is a strange thing. As you create the work, the events you’re creating recede. The world moves so much faster then your paintbrush. The motion in these pieces is just as much about that—an attempt to show how ungraspable, how impossible to hammer down that year was.

The woman is the idea. Good idea, bad idea, that doesn’t matter. She’s the concept that all the actors are creating or destroying. The ungraspable, unrealizable simplicity hovering over the chaos.

AR: I would be grateful if you would expand on your understanding of political art. For me, that phrase has always struck me as redundant, and even troublingly so. What is non-political art? Even if it is not explicitly so, must not all good art be in some sense political? If no, what are some examples of good, non-political art, and could you tell me what makes them “not political”?

MC: One could argue that all art is political in the same way that they argue everything is political. The vapid, loft-filling sculptures favored by plutocrats don’t have a hell of a lot of content themselves, but their existence is a symptom of the plutocracy. I remember looking at a book on baroque design, and finding a gold plated, cherub-encrusted carriage for a toddler to be pulled around in. I thought about the labor involved, the skill, the cost of getting materials in pre-electricity. No just society could have hand-made, gold-plated toddler’s carriages. That object’s existence is bound up with Versailles.

But, that’s politics as implicit. Politics are often explicit. Diego Rivera’s murals are explicitly political. That’s what I’m talking about when I say political art.

AR: Something you’ve said stands out to me: that “Maybe art and action, maybe, possibly, they can justify each other.” It’s a beautiful statement. I think a person may conceive of action justifying art—the question of art’s utility is always, perhaps nefariously, raised. But in what way can art justify action?

MC: Life is messy. We live in meat shells. We die cruelly and pointlessly. We can barely even grasp what’s happening to us before it’s gone.

Art takes life as its raw material and gives them meaning.

When you make art about real events, a participant can look at it later. Maybe what they did ended disastrously. Maybe all the people they worked with now hate each other. Maybe the whole thing blew up in their face. But here’s a representation of their project. The representation is beautiful. And the representation, as much as their action, may inspire someone to take up the cause again.

And then that person says, “Oh—maybe what I did was worth it.”

✖