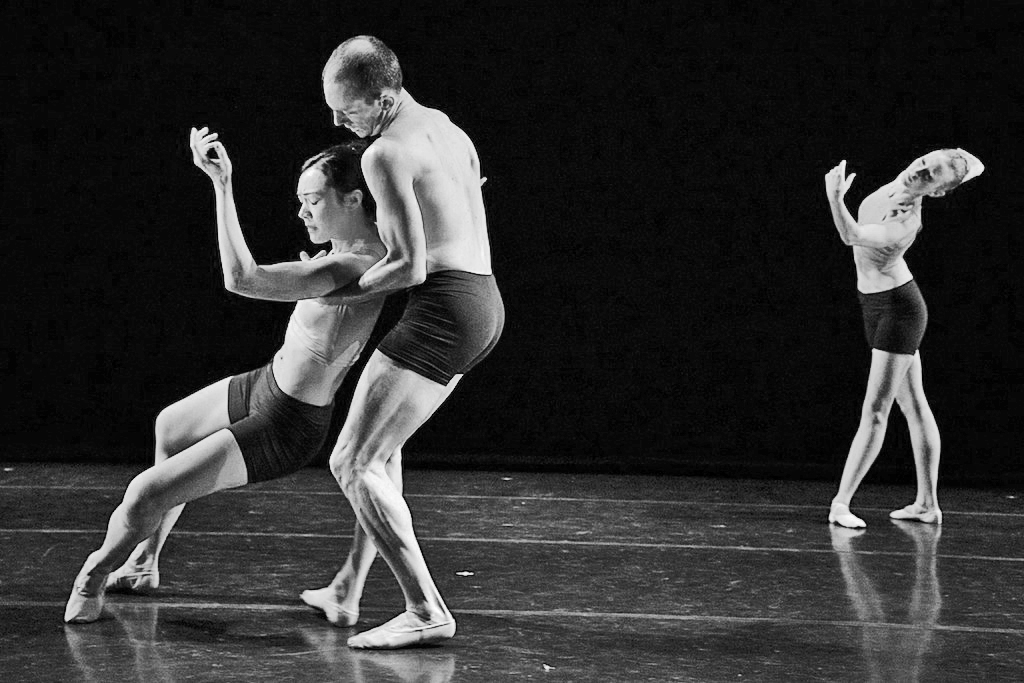

The American Reader asked five questions of Emery LeCrone, one of the most promising members of a new generation of choreographers working within the framework of classical ballet. Her dances abstract traditional forms, imbuing them with a sense of immediacy and emotion. In Bach Interpreted, a piece which will premiere this weekend as part of Guggenheim’s “Works and Process” series, LeCrone created two exegesis (one classical, the other contemporary) of the Partita No. 2 in C Minor. How does one use the same sounds to achieve different formalistic ends? LeCrone discusses this, before reflecting on the visceral connection shared between all human bodies.

—Madison Mainwaring

✖

AR: Most artistic directors and choreographers working within the classical tradition are men. The names I grew up with—George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, Marius Petipa—well, they’re not women, and I guess I always looked at the dancing, especially the interactions between men and women in the pas de deux, with the idea that it originated from a male perspective. You’re one of the few exceptions working in the industry. Does your position as a woman, and your experience in a woman’s body, impact the way you make pieces?

EL: I don’t change my process when working with a man or working with a woman. I look at dancers as if they were colors. It has nothing to do with sex. A woman can move like a man, and a man can move like a woman. Expression of their personal energy, what shade they are—that’s where the influence comes from.

I pair girls together a lot when I’m creating duets, and that’s probably because I know more about how the female body moves, while I have no preconceived notion as to how a male dancer goes about achieving a complex lift [of a partner].

AR: The title, Bach Interpreted, suggests a vivid encounter with the score. Can you describe how you listened to music in the studio, before you began working?

EL: There’s a recording by Martha Argerich that evokes the actual rise and dream of the performance. That was the first rendition, which is a recent one, that I came across.

Most of the movements have two repetitions built within. In other words the pianist plays all the way through the first half then repeats that section before moving on to the second half and then plays the second half again all the way to the end. It’s very structured, and it’s very clearly notated as to how the pianist should play it.

AR: I’ve always liked Bach’s partitas because of the distinct contrapuntals—you can almost feel the two hands on the piano, sometimes in syncopation and sometimes out. They waver between declarative harmony and the nonchalance of a sort of mismatched duet. Can you take apart a piece of the music and explain how that was countered in your choreography?

EL: What you just described is actually written into the “sinfonia,” the first movement. There’s a part where the exact melody is played twice, first with the right hand and then on the ground base with the left hand. When I read that in the score, and a piano player demonstrated the part, it was intriguing—it’s written the same way for each hand, but it sounds so different. There’s a lot of repetition in the score, but at times you don’t know it because of the different accents and syncopations.

AR: Bach Interpreted will be a two part work, the first in the classical tradition while the second is contemporary. What, in your opinion, is the difference between the two styles? And why classical, today? How would you like to see the form change?

EL: There’s a crossover where there’s a shared history and technique. You have classical, you have neoclassical, modern, and contemporary. The second piece on the program is in the contemporary vein, but it comes from the classical training that I have as a dancer. I can’t divorce myself from that.

In my vision of classical dance, the choreographic process would become more like one usually reserved for the contemporary style. You have principal and soloist classical ballet dancers who, for the most part, are committed to the company they work for. Unless you’re a resident artist at the company, it’s impossible to have access to those dancers because their technical precision is in such high demand. You can’t just get some people together in a room with hardwood floors. You have to have a marley [vinyl] floor. You have to buy pointe shoes.

AR: I’ve always like the idea of a universal language, a communication outside of words. Music usually gets all the credit for being such a language, but I think it’s achieved in dance, too. The relationship between the audience has to be very human one, even if the vocabulary of the dance is not of the natural kind. It’s interesting to have that relationship exist in what’s considered a post-modern world where that human connection has been questioned.

EL: There’s something remarkable about how much we can perceive nonverbally about the world and about each other. There’s a universal understanding of emotions through the physical world. I try to tap into that as best as I can, working with the person, who is also a dancer, in front of me. There are beautiful pieces that don’t work because they don’t consider the dancers as people.

We can all relate to what’s on the stage because we all have a body. We manifest pain, joy, and happiness. Maybe it doesn’t feel the same way from one person to the next, but when you’re looking at a human being, there’s an innate response. Like when you’re walking down the street and you see someone fall over—we react to that because it’s another body in space, like our own bodies in space.

✖