Testimonies on public misconceptions of life in prison, what goes underreported in the media, and how the system runs counter to rehabilitation.

Mass incarceration reverberates through American communities in countless ways. In addition to the 2.2 million people held in the nation’s prisons and jails at any given moment, another 4.8 million are under correctional supervision on parole or probation. Prisoners’ families face financial hardship, psychological distress, and social stigma, and 2.7 million children have a parent behind bars.

The carceral state warps the democratic process, as prison-based gerrymandering—drawing legislative districts around correctional facilities where inmates are counted as “residents,” but barred from voting—transfers political power from urban areas with high incarceration rates to rural areas housing penal institutions. Disenfranchisement follows former prisoners home, translating racial disparities in sentencing to political participation: 5.8 million people, and one in thirteen African Americans, are denied the vote because of felony convictions.

And corrections expenditures are a heavy burden on taxpayers. State and federal spending on incarceration reached $80 billion in 2010, with plenty of funding siphoned off to pad the pockets of prison profiteers who’ve built big business in the industry.

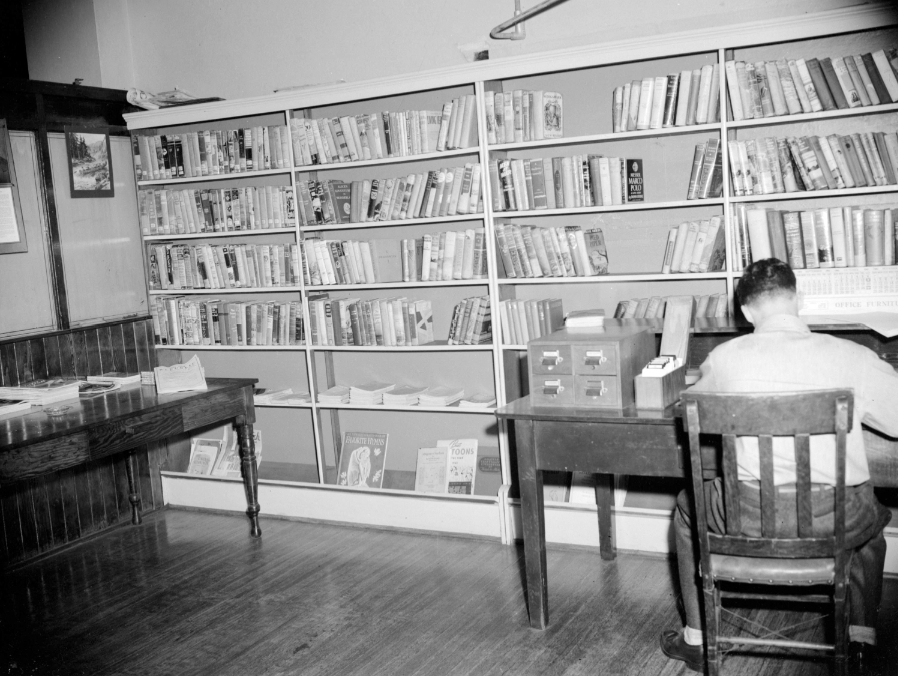

Yet while recent years have seen an uptick in political debate surrounding U.S. prisons, media coverage remains strikingly disproportionate to the number of people impacted by the system. Writing for Nieman Reports, Dan Froomkin surveys the shortfalls of criminal justice journalism, and the obstacles facing reporters, arguing that a lack of access diminishes investigation—and thus the public’s understanding of what goes on behind bars.

In a study of prison-access policies relating to the media, journalist Jessica Pupovac found variation across state systems but identified one underlying theme—discretion to grant or deny journalists access tends to lie with individual public officials, rather than follow from consistently applied policies.“Too often these individuals deny journalists access not because of security concerns, but because they fear the anticipated content of a story,” she says. Some states prohibit face-to-face interviews with inmates, while others ban photography and recording devices, or require that interview questions be cleared in advance. Often, the process itself lacks openness—access can be withheld without explanation.

Experts in Froomkin’s report attest to the impact this lack of transparency has on prison-related reporting. Ted Gest, founder of Criminal Justice Journalists, describes coverage as “crisis-driven.” The Southern Poverty Law Center’s Jody Owens says writers are “not necessarily appreciative of the day-to-day struggles” of inmates. And Paul Wright, editor of Prison Legal News, notes that, “normally well-intentioned or hard-nosed journalists…tend to take statements by prison officials or government officials at face value, with no type of critical disbelief.”

Wright—profiled here—addresses these issues by working with incarcerated writers who report and file well-researched stories on the human rights of those detained in correctional facilities. But prisoners with less journalistic training, too, have sought to expose the misconceptions the public holds of life in prison, and the underreported abuses they experience everyday—serving as witnesses to their own experience. Researching this range of prison writing, I corresponded by letter with individuals whose testimonies from the inside deserve to be read in fuller form. What follows are excerpts from some of the interviews I conducted.

—Andrea Jones

How did you begin writing for a public readership?

When I came to prison, I had a ninth-grade education and was for all practical purposes functionally illiterate. I earned my GED, but then found out that on death row, we are prohibited from participating in any form of educational or vocational programs. I started reading all I could, and taught myself to write, as through writing I could escape the reality of my fate and reach out into the world beyond steel and stone.

Being condemned to death is unlike any other experience imaginable, as by such condemnation society has declared that we have virtually no redeeming value and must be put down like rabid dogs. I hope to dispel the myth that the politics of death so deliberately perpetuates, by putting into words how I feel and attempting to show that we’re not the stereotypical “monsters” we’re all made out to be.

My first published essay was about the overwhelming despair resulting from the physical, emotional, and even spiritual “isolation” of death row; the paradox of living in close proximity to a hundred other condemned men, yet having the inescapable feeling of abandonment. I understand those who support the death penalty because they see the often unspeakable ruin and suffering of the victim, that they feel morally justified in demanding vengeance upon those who have been convicted of brutal crimes. But they suffer from tunnel vision, making the conscious decision to take a life—irreparably compromising the sanctity of life as a whole—and justifying it by seeing only what they want to see. And they are then responsible for sending the innocent victims of our inherently imperfect judicial system to their death.

In later essays, I ventured beyond how I personally felt and reached out to paint a picture of humanity among the ranks of condemned men—the need to compel the reader to understand that what we are put through under the pretense of administering “justice” is comparable to other unconscionable atrocities. My most important stories were those written in memory of those who have been put to death, such as tributes posted about Billy Van Poyck, Manny Pardo, and Larry Mann. If there is a fate worse than death, it is to be forgotten as if you never existed in the first place. No person should be forever defined only by their one worst moment, but should be remembered for what was good within them.

—Michael Lambrix, Union Correctional Institution,

Raiford, Florida

My specific motivator was the race-baiting senator, Jesse Helms, who was sponsoring legislation to expel prisoners from the Pell Grant program, which was by far the chief, if not sole, funding source for the majority of prisoner-college students across the country. I wanted to provide a reasoned voice from the inside out as to the shortsighted, inimical positions and policies so trumpeted and supported by the tangentially aware. Too much of what I saw in the mainstream media was rote stereotypes promulgated by politicians advancing other agendas, using crime and punishment as popular distraction from the underling causal factors of difficult societal concerns.

After having struggled, even with Pell Grants, to finance my undergraduate education, I knew it would be impossible for most prisoners to ever matriculate into post-secondary opportunities without Pell assistance. It was my intent to “educate the public about these bone-headed, ultimately self-defeating actions,” so they would enact self-enlightened and thus self-serving policies. Education is the “best bang for the buck” society can invest in.

After two decades of this effort, though, I’ve come to the sadly distressing realization that the comprehensive efforts of myself and others have not been sufficient, or in the words of one prison official, “God forbid young man, don’t confuse the situation with facts.” For facts don’t matter, emotion rules the day, and politicians manipulate for their own shortsighted agendas while all others be damned.

—Jon Marc Taylor, South Central Correctional

Center, Licking, Missouri

At the age of twenty-two, I was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for a first-time, non-violent drug offense and to say I was angry with my circumstances is an understatement. I had a lot of anger and rage and I needed a way to release it, somewhere to focus it. I started my sentence in 1993, and was into all types of things—drugs, violence, more crime—all while in prison. I was what they call “in the mix”: self-destructive, looking for drama, and courting chaos. Finally, around 1999, I got a clue and started to write. I took some classes on journalism and I found it was something that interested me very much: the idea of being published, the idea of people reading what I wrote and caring about what I said, the idea that I could make an impact from my prison cell with my words.

I started writing about the circumstances of my case and the injustices of the drug war in general. I then found a niche writing about prison basketball, which evolved from there into documenting prison gangs, life on the inside, hustling, and drug recovery. When I am released, I plan on doing a documentary series about all the people and gangsters I’ve covered in my work, looking at the failed war on drugs and unnecessary incarceration rates. I plan on being involved in any hearings that take place on the state of incarceration and draconian sentencing in America, and hope that I can shed some light on what’s wrong with our system of justice so that legislators can enact change so others don’t have to endure what I have. I have been buried in prison for twenty years and am resolute that my voice will be heard and changes will be made.

—Seth Ferranti, FCI Forrest City, Forrest

City, Arkansas

What topics do you keep coming back to as a writer?

The most important articles I feel I have written concern privatized prisoner medical care. The public, understandably, can begrudge us prisoners the free medical care we receive, but as the courts have said in declaring it to be a constitutional right, we do not have the option of going out to seek care, nor can we purchase health insurance, or otherwise obtain care when ills befall us. I find this topic important because the private medical contractors, as a whole, have an atrocious record of saving money while sacrificing lives that could have been saved. In some cases, it was basic care that was initially needed, but failure to provide it resulted in an irreversible worsening of the malady. Far too often, it was people in prison or jail for minor, non-violent crimes, whose short sentences became death sentences. Yet, the public is paying for care to be provided. These companies have a business model that aims to save costs by cutting staff and care, and if a catastrophic event occurs, by paying a confidential settlement on the rare cases that survive procedural court hurdles as pro se litigants or the efforts of their estates’ lawyer.

—David M. Reutter, Sumter Correctional Institution,

Bushnell, Florida

What misconceptions do you think people on the outside hold of life in prison?

Some misconceptions are based on the exaggerated crap you see in prison movies. Very rarely, at least in Virginia’s women facilities, do you hear of someone using a weapon to hurt someone else. Occasionally, there will be a violent fight, but for the most part women just argue loudly. We do form friendships that last and try to take care of one another. If someone is seriously ill, we pitch in and help with whatever is needed. Granted, my incarceration hasn’t been the average kind: I’ve been on the lifer’s wing for most of my time. But for every crappy thing that happens (because this is prison), I hear of remarkable acts of kindness. For every ugly word spoken in anger or hurt, I hear about the encouraging stuff more often. Nevertheless, I think when we become convicts we lose our humanity, as far as the public is concerned. We stop being people and become some cold, uncaring, violent, uneducated animal not to be trusted at all.

—Christi Buchanan, Fluvanna Correctional Center,

Troy, Virginia

That everyone in prison deserves to be there. That the overwhelming majority of prisoners have nothing to offer society. That they are deadbeat dads, drug addicts, sexual deviants. It’s a broad-brushing designed to inflame the passions and prejudice of the misinformed public. Life in prison is the most degrading experience any human being will ever endure. Untold prisoners are innocent. Incredibly talented. Graterford prison houses some of the most gifted guys I’ve ever met. They raise funds for college scholarships for underprivileged kids, they’ve established mentoring programs, programs that connect absent fathers with their children. A lot of prisoners want to give back. We are remorseful.

—Reginald S. Lewis, SCI-Graterford, Graterford,

Pennsylvania

I think the worst misconceptions have to do with believing mindlessly that the police rightfully arrest people 100 percent of the time. People want prison writers to focus on our atrocious, torturous conditions of confinement—because they do not want to face the reality that our “justice system” is not just, especially not for people who cannot afford paid counsel. If we focused more on holding the cops and courts accountable for gross misconduct in wrongfully arresting and prosecuting innocent people, that’d be a substantial first step in fixing what’s wrong with this system.

—Dr. Cathy Marston, Dr. Lane Murray Unit,

Gatesville, Texas

What people don’t consider is that being absent from your family, loved ones, and friends is damaging to a degree difficult to describe. I’m diligent about sending Christmas cards, birthday cards, and letters to people (almost to a force-the-relationship degree), but even still, I don’t have any of the friends I used to have. I’m lucky in that I have a bunch of great friends—but none of the ones I had prior to prison that I expected would be able to at least keep me on their Christmas card list for these eighteen-and-a-half years. I was wrong.

And the way prison can mess with families is brutal. I’m grateful that I don’t have kids (though I want them when I get out) because I’ve been on the opposite end: my father went to prison when I was about fourteen and stayed until I was twenty-one, and I know what it’s like to feel that loss. It didn’t help that he’s not a writer and I could count on my thumbs how many times he wrote to me over those years. For the most part, I think, I’m the rare exception in prison, a guy who can just write and write and write. Often, it’s an overcompensating factor that tries to make up for being in here: having paper relationships instead of real ones. The only two family members I’m close with are my mother and my sister—both of whom have been tremendously strong during all this time. Most families can’t stand the strain of prison. It breaks them. There’s a sort of overused phrase about family members and the loved ones of prisoners: that they’re doing time, too. To a degree, that is true. Most people don’t understand the amount of pain that loved ones go through when a guy is sent to prison—pain that isn’t just a one-time thing, but something that reverberates every missed holiday, birthday, and special outing.

—Jeff Conner, Washington State Reformatory

Unit, Monroe, Washington

What kinds of issues impacting prisoners do you feel are underreported in the media?

Part of the problem is that not enough light or attention from the outside makes it into the world of the incarcerated. The other part is complacency by those involved in the system, on both sides of the fence. When a lack of exposure is mixed with complacency, you encounter a series of abuses accepted simply as “the way it is.” The unacceptable status quo becomes the accepted and expected level of care, treatment, and management.

The use of Special Housing Units (SHUs) constitutes one of the most damaging human-rights abuses in prison. Whether called “control units,” “lockup,” “the hole,” or “the box,” solitary confinement is for prisoners who are either being disciplined, are under investigation for alleged misconduct, or are in protective custody. Here, prisoners are housed in small, one or two man cells for twenty-three to twenty-four hours per day. In federal facilities, prisoners in the hole receive five hours of recreation time each week, five hours out of their cells locked in a new, outdoor cage with walls and bars—really, a dog run—which has fencing for a roof.

Even mentally sound prisoners experience bouts of aggression and severe depression in these conditions. Some suffer from disorientation, incoherency, and erratic thinking. Mentally ill prisoners are worse off. It doesn’t take a mental health expert to realize that locking a human in a tiny isolated cell, subjecting him to severe sensory deprivation, and cutting off contact with the outside world is harmful. Add in sadistic treatment by some guards that can reinforce prisoners’ feelings of worthlessness, and you have the recipe for a badly wounded person. I have experienced this, and know how damaging it can be.

Medical problems represent another crisis point: prisoners are not provided medical or dental care commensurate with basic health standards. I’ve been waiting eighteen months to have two cavities treated by the staff dentist at FCI Petersburg. I’ve been waiting two years now to see an optometrist for a new prescription for my glasses. While not life-or-death matters, these are serious medical deprivations.

My cellmate has a neurological problem with one of his legs, and over time I’ve watched this problem persist and his functioning decrease. He now injures himself regularly trying to walk. He’s been on the “waiting list” for the last eighteen months to receive “authorized treatment.” This is just one cell out of fifty in the F-North Housing unit of FCI Petersburg. It’s as if we’re in some underprivileged, remote area, waiting for a doctor to arrive by riverboat.

—Christopher Zoukis, FCI Petersburg,

Petersburg, Virginia

There are many men who simply don’t belong in prison; they belong in Western State Mental Hospital. But in the eighties, the federal government cut funding for most mental institutions and most guys that needed medication and supervision were deposited on the streets, where eventually, many of them committed crimes and ended up in prison, where they are, to some extent (but not enough and not properly) medicated as a way of keeping them chemically restrained. This is a major problem that only seems to grow with each year—not only in the numbers who run to Pill Line for their daily (or thrice daily) pills, but in the conditions of these guys who are not getting better and are not getting treatment.

Solitary confinement—time in Intensive Management Units (IMUs)—is to me, inhumane, at least when used for long-term warehousing of “difficult” prisoners. Having been in prison for seventeen years now, I have seen quite a few guys who have made “the hole circuit” (where you’re shuffled from one prison’s IMU to another prison’s IMU for, sometimes, up to five years or more). The guys that survive often aren’t the same sort of men. I don’t mean they’re broken (sometimes a hole circuit will create more erratic, disobedient behavior than was originally there in the first place), I mean that they actually lose their minds. Or at least their ability to socialize in a way that is anything approaching appropriate. It’s the creation of mad dogs, to put it metaphorically (but rather accurately).

I’m not a law library expert (having signed a plea bargain for “only” eighteen-and-a-half years in order to avoid the threatened forty-five years), but it came as a shock to me that there is a time limit on justice. During President Clinton’s time in office, he signed a law that limited the amount of time a person could appeal his case (for ineffective counsel—an entirely too common reason for retrial—and for other legal considerations). Certainly it makes sense to stop frivolous cases from proceeding, but this stops legitimate cases, too. And when someone is poor, or, like me, inexperienced with the justice system and accepts whatever they tell you, you can often sign away your rights (like I did, not knowing that there was no way that I could have gotten forty-five years for a bank robbery and an attempted murder). The time-barring of cases is yet another way of making sure that those who have money don’t have to serve as much time as others because they’ve got lawyers that appeal right away, instead of guys who come to prison and, if they’re lucky (and smart), eventually learn their actual rights in the law library.

—Jeff Conner, Washington State Reformatory

Unit, Monroe, Washington

Have you ever been retaliated against for your writing?

I’ve been put in the hole more times than I can count for my writing. I have been transferred. I have had my mail seized, held, and not delivered. I have had my commissary, phone, email, and visiting privileges taken away for months on end. I’ve had my prison job change unexpectedly, had programs or perks I was enjoying taken away. I have been placed under a microscope due to my writing. Imagine every incoming and outgoing letter read and scrutinized for hidden messages, to see what you are planning writing-wise. This is what I’ve been subjected to by the BOP, all in the attempt to get me not to write.

—Seth Ferranti, FCI Forrest City, Forrest

City, Arkansas

What aspects of the prison structure do you feel run counter to the idea of rehabilitation?

My experience is that prisons don’t really provide much at all in terms of socialization, normalization, education, or rehabilitation. Prisons are about security and control, with the fence or wall as the restraining barrier. The goal is to keep everyone, everything, and all conflicts contained therein—physical, metaphorical, and ideological included. The operating principle is that prisons should constrain people, thoughts, and ideas so that they are not visible, or offensive to, the outside community.

The goal of prisons today is to warehouse as many prisoners as possible, as securely as possible, while utilizing the least amount of resources, like staff, materials, space, and funding. This ideology runs against true reform, but certainly requires more fences, cameras, and prison unions, benefiting many who make their living from the system. There’s a lot of inverted thinking.

From the prisoner’s first day, he is confronted with the reality of oppression, officially sanctioned through inaction. As the prisoner approaches his counselor for the first time—the prison guard who deals with bunking assignments, working assignments, and other basic living conditions—he’ll probably be scolded for seeking the counselor out so quickly. The prisoner will be forced to understand where he can and can’t sit in the chow hall. At FCI Petersburg, the tables are generally divided by race. Sound like a real rehabilitational environment? Sometimes, the prisoner will have the privilege of having his cell torn apart by an agitated prison staffer, who will leave all of the prisoner’s property on the floor for the prisoner to clean up. The thin mattress, too, will probably have the sheets torn off. There is nothing quite like returning to your cell and seeing all your earthly possessions discarded on the floor, as if they mean nothing. They might not be much, but they’re all we have.

The system is based upon security, control, and failure. This anti-rehabilitative environment is evident from the way the majority of prison guards treat prisoners to the way prisoners treat each other. If the prison administration is not supporting oppressive tactics being used against the prison population, then they are allowing prisoners to oppress fellow prisoners.

And we come full circle. You ask me, as many are right to question, what components of prison life run counter to the ideals of rehabilitation? But I am left with the inverse of the reasonable question: “What components of prison life are meant to fulfill rehabilitational ideals?” The answer is very few.

—Christopher Zoukis, FCI Petersburg,

Petersburg, Virginia

What are your suggestions for reform?

I think that the whole concept of corrections needs to be reevaluated. Currently, it seems to be about catching the bad guy, punishing him, and monitoring him for violations of supervised release terms or further criminal violations. This is a system based upon failure, and amounts to a revolving door of recidivism. What we need is a system based upon success.

I believe that when someone is caught breaking the law, they should be held accountable for their actions, but also supported in the reformation of their character. If a diversionary program is applicable (drug courts, treatment, etc.), then it should be utilized to help the lawbreaker with whatever issue is ailing him (substance abuse, mental health concerns, etc.). This is more of an issue- or cause-based approach to the treatment of crime.

If the person must be sentenced to a period of incarceration, then release preparation should begin on Day One. Upon admission to the prison system, prisoners should be evaluated and their needs identified. Think of this as an individualized education plan or an individualized reformation pathway: a map that shows what help prisoners should receive during their term of incarceration. Then programs must be offered in the educational, rehabilitational, and vocational tracks.

There is a lot of debate about what sort of education prisoners should be allowed to receive and at what expense. Some—whose voices seem to be the loudest—feel that nothing should be offered. There are not a lot of high quality options for prisoners who lack financing, and most prisoners fall into this economically disadvantaged category. But it’s clear to those of us who study the education and rehabilitation of prisoners that education is the single most cost-effective, proven solution to crime and the plaguing problem of recidivism. We could spend a fraction of what it costs to house a prisoner for a year to provide him or her with an academic or vocational college-level education, and produce significant return on the investment.

A Texas study found that prisoners who earned an Associates degree recidivated at a rate of 13.7 percent, those with a Bachelor’s degree at 5.6 percent, and those with a Master’s degree at 0 percent—much better than the 60 percent rate for those without degrees. It’s money in the bank through reduced prison populations, and former lawbreakers working for a living, not being provided for by American taxpayers.

The final step of the process would be reintegration. The first few weeks after release from confinement are critical to the prisoner’s success. Some handholding is needed, as is a healthy dose of support services. As prisoners walk out the prison gates there should be a case manage or reentry specialist there to pick them up, help them locate housing, food, clothing, and other life necessities. Ex-prisoners should be given a helping hand until they can fend for themselves in a legal and law-abiding manner.

We can’t expect people who have been thrown in the criminally driven world of American corrections for decades to magically flip a switch and thereafter always make the right decisions. But we can help them deal with their demons and receive the treatment they need, provide educational and vocational services, and support their reintegration back into society. If we provide them with the tools required, then they can succeed. But if all we have for lawbreakers, or recently released lawbreakers, are a contemptuous look and a wagging finger, then we might as well be advocating for softer prison mattresses and better ladders to climb up into them with. The choice is simply success or failure. The question, though, is not an easy one for many to answer: “Are we ready to start succeeding, or are we content with failure?”

—Christopher Zoukis, FCI Petersburg,

Petersburg, Virginia