Atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale. — Catullus

We’ve been writing about loss for millennia, and about the loss of brothers in particular for almost as long. Catullus wrote his famous 101st poem, ending with the line “and forever, brother, hail and farewell,” to the ashes of his dead brother more than two thousand years ago. His falls in a long line of poems about the death of loved ones, and this tradition survives in the form of poems like Michael Dickman’s “Dead Brother Superhero.” (As a side note, you might want to check out the full text of the poem over at The Academy of American Poets before you continue reading.)

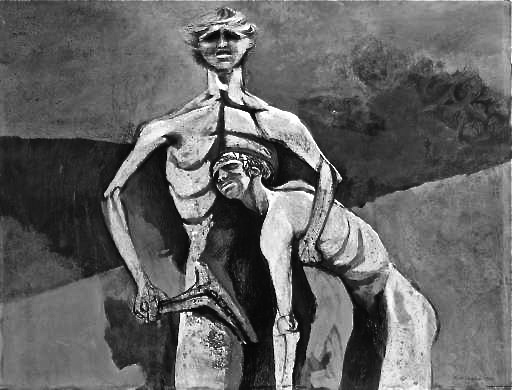

“You don’t have to / be afraid / anymore” Dickman begins, simultaneously addressing and assuming the persona of his superhuman dead brother. This duality persists in the form of his brother’s “super-outfit” that’s “made from handfuls of shit and garbage blood” yet is “pinned together by stars,” a man who at once “looks down from outer space through all the clouds” and “out / from the center of the earth / through the fire”, who “stopped and started the bullet in my heart.” It’s hard not to think of our brothers that way: simultaneously looking down on us and up to us, comprising blood and stars, injury and salvation.

What strikes me most about this double nature is Dickman’s blending of the contemporary superhero mythos into the conventional elegy. This mixture lends the writing an honesty, a modern earnestness, that would go missing in a more traditional poem. “Dead Brother Superhero” doesn’t sit comfortably in the museum of Poetry About Death, but it also doesn’t fall prey to the ephemerality of so much work steeped in popular culture. This hybridization reinvigorates the tradition of poetry about loss, reaching its peak in the final image of his dead brother’s eyes closed, “His cape sweeping the floor.” We can feel the influence of the dead, of the memory of their lives, as viscerally as the knowledge that their death is also the source of their powerlessness.

My own brother died thirteen years ago, and though I think of him less often than I did immediately after his death, the vividness of him persists: I still have a hard time believing I’ve lived longer without him than with him. The presence of the dead in our lives is a paradoxically potent force, and I’m most moved by Dickman’s ability to immediately grasp and communicate this truth. The tension of that self-contradictory realization—that the dead have no powers and superpowers all at once—coupled with the emotional salience of his imagery and the sparseness of his lines—makes Dickman’s work particularly memorable. And that is, after all, the point: to preserve something or someone in memory, in writing beyond the limit of that thing or person’s natural existence.

I also appreciate the dreamlike quality, the meditative silence, that pervades “Dead Brother Superhero.” No one speaks, save the narrator’s whispered “To the rescue”; this apostrophe, this fierce imagination focused on someone not present, says more about the narrator’s relationship with his brother than any anecdote or essay. I once read or heard—I can’t remember where—that the definition of writing poetry is knowing when to shut up. The balance of story and silence in this poem clearly proves that Dickman knows not only what to say, but how much.

The resolution to the seeming paradox—the fulcrum of the see-saw balancing narrator and brother, garbage and stars, the looking outward and the looking inward, power and powerlessness—is Dickman’s understanding of superhuman ability as literally being beyond human ability. It is outside of it, being more and less than what we are while alive, entailing both the tremendous gifts and terrible costs of death. We know and remember what our brothers have done and said. We can only imagine the possibilities of what they could have done and could have said. Their absence renders them less to us than what they were; it also magnifies them to superhuman size in our memories. They’re with us as long as we live and they’re gone almost as soon as they arrive. All we can say is: thank you, brother. Hello and goodbye.