Anyone who has scanned the poetry shelves of a well-stocked Barnes and Noble will have seen the name of the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Along with Neruda, the Chilean bard, and Rumi, the Sufi mystic, Rilke is one of the few foreign poets to have made it big in America. It isn’t hard to understand why. Pretend, for a moment, that you are having a garden-variety emotional crisis. Your job has recently siphoned off your last kilowatt of youth, Janet from Human Resources hasn’t replied to your Facebook missive, the bars in Flagstaff or Buffalo play the same three inane songs, and existence itself has begun to feel like a passive-aggressive feud. And yet, inexplicably, you harbor a weird affection for life in the abstract—a blue flame of gratitude for your place in the world—even when your insurance provider keeps you on hold for over an hour. The paradox is inexpressible. You assume that you are uniquely troubled. But then you open an English version of Rilke’s Duino Elegies (say, for example, the one translated by Galway Kinnell and Hannah Liebmann):

Who, if I screamed out, would hear me among the hierarchies

of angels? And if one suddenly did take

me to his heart: I would perish from his

stronger existence. For beauty is nothing

but the onset of terror we’re still just able to bear,

and we admire it so because it calmly disdains

to destroy us. Every angel is terrifying.

Angels—now, that’s something. You may have seen the statistic, often cited by foreign journalists and talk-show hosts, that 77% of Americans believe in such ethereal beings, but this is the first time you’re hearing about a celestial bureaucracy. You don’t believe in angels; the idea is obviously absurd. But then again, your life is absurd, and so is your “worldview.” Your agnosticism allows you to be a sensible, tolerant citizen, but certain moods do not respond to irony, sports, or single-malt scotch. Badly out of sync with the world, you begin to rely on a daily routine to set your mind at ease. You settle for being half alive. Your spirit becomes a ghost. It’s in this regulated state that you discover the higher vice of poetry:

Ah, who can we prevail upon

To use in our need? Not angels, not humans,

and the insightful animals already note

we’re not very securely at home

in the interpreted world.

The interpreted world! Translators quibble over how to handle the German phrase der gedeuteten Welt (“deciphered world” is another option), but either way, you get the gist. That is where you’ve been trying to live, and failing all along! Also, you’re glad that someone else has sensed that animals know we are frauds. Your colleague’s goldfish, your neighbor’s cat, the panther at the zoo—these creatures truly belong on earth, whereas you are just a cosmic tourist, a hopelessly transient stranger. Rilke is letting you know that this is part of the human condition:

But we, when we feel, pass off in vapor: we

breathe ourselves out and beyond, from ember to ember

we yield a weaker scent…Like dew from morning grass,

what is ours fumes away, like heat from a

warm dish.

You have read many interpretations of the world. In fact, you may have spent your college years cooped up in a plush library, grappling with the Teutonic syntax of other German men: Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Freud, Marx, Weber, Heidegger, Einstein. Rilke, though, cuts to the quick; his question is basically this: Can we exist without the aid of angels, gods, myths, or spirits? Do we always require a customized symbol of transcendental meaning, something that—as he puts it in the Elegies—“enraptures, consoles, and helps us”? If so, why? And how should we settle the matter? If we can’t survive on a steady diet of late-night satire, self-help jargon, and layman astrophysics, and if we can’t fully embrace the doctrine of any major religious community, where then should we turn? For most of us, it’s romantic love. Rilke knows this—he’s beaten us to it—and he gently rebukes the lover in us. “You embrace,” he writes, “but where’s the proof?”

Lovers, are you still who you were? When you lift yourselves,

one to the other and touch lips—: drink upon drink:

oh, how strangely the drinker is missing from the act.

Love, here, is as real as angels. Do Americans believe in love? The polling data is harder to find, but evidence suggests that Americans, in their messy way, trust in transcendental love as much they do in flying Gabriels. For Rilke, both concepts exist in the same otherworldly realm:

Angel! If there were a place we know nothing of, and there,

on some ineffable carpet, beloveds who never

accomplished it here could show at last their

heart-swings’ bold high-flying figures,

their towers of rapture, their ladders

leaning a long time only on each other

on ground that never existed—and, trembling, could do it,

before spectators crowded round, the innumerable

speechless dead:

would these then toss down their last, forever saved up,

ever hidden away, unknown to us, eternally

valid coins of happiness, before the finally

truly smiling pair on the quietened

carpet?

The question is exhilarating and tragic. Exhilarating, because Rilke rejects the tenets of Christian cosmology: he wants there to be a place where perfect human love can happen now, not in some metropolis of clouds at the end of time. Tragic, because it won’t ever happen—there is no such redemption. And yet we crave the ineffable carpet. We stake our lives on a glimpse of it. We need to believe that love will save us from our divided selves.

If not Salvation, Love. If not Love, Beauty. If not Beauty, well, I guess we’ll settle for Happiness. But even that is a kind of illusion. By the time we reach the Ninth Elegy, Rilke has taken us into the vortex of our inadmissible dread. Why, of all possible forms of life, do we have to be human—absurd creatures who, “avoiding destiny, long for destiny?” Here is how Kinnell and Liebmann choose to translate the poet’s answer:

Oh not because there is happiness,

that rash profit taken just prior to impending loss,

not out of curiosity, or to give the heart practice,

reasons that would hold for the laurel too…but because being here is so much, and because everything

in this fleeting world seems to need us, and

strangely speaks to us. Us, the most fleeting. Once

for everything, only once. Once and no more. And we, too,

only once. Never again. But to have been,

this once, if only this once:

to have been of the earth can never be taken back.

Let’s face it: Janet from Human Resources won’t respond to your Facebook post. Work won’t get any easier. Ember to ember, you will continue to yield a weaker scent. There’s even a chance your Barnes and Noble will close its doors for good—replaced, perhaps, by a group of coders whose algorithms will henceforth govern your reading life. But here you are, for the moment, alive, irrevocably of the earth. Rilke, when he wrote poetry, said his veins were “full of existence.” Your veins are full of coffee. Still, you’ve just been witness to the praise within the lament, which is poetry’s equivalent of photosynthesis or Special Relativity. Rilke has made you, however briefly, proud to be a human being, filled with sadness and wonder at the paradox we share: we want to live in a perfect world but don’t want to leave the one we’re in, despite its imperfections. The irreducible theorem might be: We will die, but we have lived. Having lived, we are better qualified than angels to say what it’s all about. Near the end of the Ninth Elegy, Rilke offers some solid advice to fellow non-angels:

Praise this world to the angel, not the unsayable one,

you won’t impress him with your glorious emotions; out there,

where he feels with more feeling, you’re but a novice. Rather

show him

some common thing, shaped through the generations,

that lives as ours, near to our hand and in our sight.

The heavens aren’t impressed with our cities, music, rockets, stadiums, search engines, or particle colliders. What can we offer that will give them a sense of what it means to be of the earth? William Gass, author of Reading Rilke: Reflections on the Problems of Translation, has a clever idea:

A billfold. Show the Angel a billfold that has ridden in a rear pocket on someone’s rump, the creases it now contains, where money and credit cards once slid in and out, as oiled and stained as a fielder’s glove; or a boy’s pocketknife, worn short and thin from all those days he’s whittled away; or a mohair sofa, shiny where the man wearing that billfold sat, or the cat curled, or love was made.

Gass is a resourceful guide to Rilke because he takes the poet seriously—his work, Gass writes, is proof that art can “matter through a lifetime”—without forgetting that German Romanticism (“the magical movement of matter into mind”) sounds rather precious to the uninitiated. For Gass, the Elegies are a prime example of just how transgressive art can be:

When one of us turns aside from living in order to admire life; when a rose petal is allowed to cool an eyelid, when a line of charcoal depicts the inviting length of a thigh; we are no longer going in nature’s direction but contrary to it. What was never meant for us becomes ours entirely; what never had a use is suddenly all we need.

Just as an interest in poetry is really an interest in the universe, “the problems of translations” are really the problems of how to describe the world—not to mention the greater problem of how to characterize the angels. Gass takes issue with a version that reads: “Every angel is terrible” (“Angels can’t be terrible,” he writes. “Pot-holed roads are terrible.”). His own choice, though, is hardly better: “Every angel is awesome.” (Angels can’t be awesome, either. Half-priced tequila is awesome.) But Gass is remarkably sensitive when it comes to Rilke’s religious allusions (“graceshaped swans” is hard to beat), and he makes a uniquely serious attempt to sketch out Rilke’s vision:

Raum. If there were one word it would be Raum. The space of things. The space of outer space. The space of the night which comes through porous windows to feed on our faces. The mystical carpet where lovers wrestle. The womb of the mother. Weltraum.

Raum, Weltraum, Innerweltraum (space, “worldspace,” consciousness)—there’s more going on in the German lyrics than English can handle. But English readers are still invited to apprehend his message. As Gass puts it, the Elegies “demand a radical openness to the world…they invite you to think of your consciousness as a resonant, harmonizing lifeform.” They also invite you to reclaim the qualia stored inside your concepts—to consider human experience in its raw, exalted form. If Rilke’s poetry has any relevance to twenty-first century Americans, it’s because we worry, now more than ever, that we are losing unmediated experience. We’re busy, we’re sleepless, we’re medicated, and we’re marooned in the everyday.

The Rilke one encounters in recent translations sounds like a guy who can probably relate. In his introduction Edward Snow’s The Poetry of Rilke (2009), Adam Zagajewski explains that Rilke was on a mission to “become real” (or feel alive, as some might say). His own version of eat-pray-love was rather idiosyncratic: he confused the poverty of Russian peasants for noble asceticism, he cherry-picked apocryphal texts, and he fell for a woman, Lou Salome, who also had a thing with Frederic Nietzsche. His lifelong struggle to make pure art, inspired by Cezanne and the sculptor Rodin, prevented him from finally accepting any stable doctrine. It also prevented him from pursuing romance in real life (as Gass puts it: “women were the Muse, to be courted through the post.”). Because this is poetry, not biography (that section’s closer to the entrance), we don’t need to analyze Rilke in order to appreciate his art. But we do need to decide how to read the Elegies, as Zagajewski remind us: “Should we try to understand them thoroughly, or rush through them like children who run through the forest at night, half terrified, half elated?” Disenchanted adults that we are, the latter sounds rather tempting, though Zagajewski claims that Rilke is not a poet of innocence: “only silence is innocent,” he writes, “and he still speaks to us.”

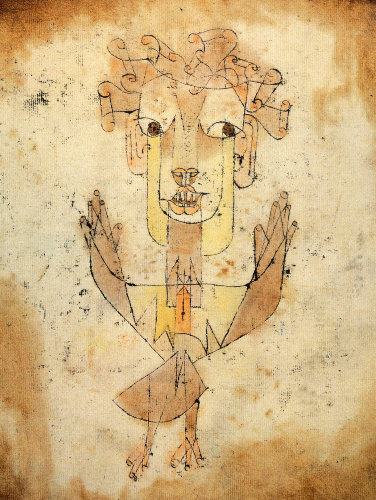

Rilke: New Poems, a collection of youthful verse translated by Joseph Cadora, marks the latest contribution to Rilke studies in English. Originally published in 1907 and 1908 in two volumes, these two hundred poems represent a period of intense creativity, including Rilke’s first attempts to broach the theme of heavenly beings. Cadora’s translation of “The Angel” stresses their predatory nature:

Do not burden his buoyant hands, for perhaps

those very hands might materializeto painfully examine you by night,

to go raging through the household,

clutching as if they created you, and might

in this manner break you out of your mold.

This is a fascinating departure from Stephen Mitchell’s translation, according to which, on that fateful night, the threatening seraph’s “light” hands

would come more fiercely to interrogate you,

and rush to seize you blazing like a star,

and bend you as if trying to create you,

and break you open, out of who you are.

To be broken out of who we are: is this what we’re hoping for? Is this why we turn to poetry? Robert Hass, who wrote the introduction to Mitchell’s, and now Cadora’s, book, claims that the Elegies are “an argument against our lived, ordinary lives.” They were written, after all, during a time when ordinary life was becoming increasingly corporatized; the composition itself was delayed by petty bourgeois concerns. As Hass tells it, one morning in late January of 1922, Rilke received a troubling business letter. He took a stroll around the castle of his wealthy friend and patron, wondering how to respond. At some point, he was inspired to write the poems that would define his career. First, he answered the business letter, and then he dealt with his cosmic vision. This is “Modernism.”

Modernist poets understood that the average person’s consciousness is narrowed, perverted, corrupted, and wasted by the burden of daily life. “Difficult” poetry was meant to reveal the reality hidden within this matrix. In contrast to the Romantic myth of the poet as constant nightingale, T.S. Eliot thought of himself as a part-time mystic. Here he is on the relationship between poetic and religious experience:

To me it seems that at these moments, which are characterized by the sudden lifting of the burden of anxiety and fear which presses upon our daily life so steadily that we are unaware of it, what happens is something negative: not ‘inspiration’ as we commonly think of it, but the breaking down of strong habitual barriers—which tend to reform very quickly.

How do we break these habitual barriers, and what are the consequences? This is a question taken up by the scholar Denis Donoghue, whose new book, Metaphor, helps to explain why poetry exists in the first place. “Rhetoric,” he writes, “is a glorious failure” (after all, it can only describe the “interpreted world”); metaphor is the bridge that connects our biological and spiritual selves. Hence the book-length study and its refreshingly straightforward thesis: “The force of a good metaphor is to give something a new life: a kind of regenerative quality that might be quantified and measured—if art has a serious impact on our sensibilities, metaphors have real regenerative power.” From Thomas Aquinas to Wallace Stevens, Donoghue shows how metaphors change the world by changing our sense of it, a point that philosopher Richard Rorty liked to put in provocative terms:

To say that Freud’s vocabulary gets at the truth about human nature, or Newton’s at the truth about the heavens, is not an explanation of anything. It is just an empty metaphysical compliment which we pay to writers whose novel jargon we have found useful…the history of science, culture, and politics is a history of metaphor rather than of discovery.

When it comes to provocation, though, it’s hard to outdo Nietzsche, whose “On Truth and Lying in a Nonmoral Sense” reaches a higher octave:

What then is truth? A movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphisms: in short, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished, and which, after long usage, seem to a people to be fixed, canonical, and binding. Truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions, they are metaphors that have become worn out and have been drained of sensuous force, coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer as coins.

Everyone is familiar with Nietzsche’s famous claim that “God is dead.” Less well known is Wallace Stevens’ “Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction”: “Phoebus is dead, ephebe. But Phoebus was / A name for something that never could be named.” Stevens, like Rilke, understood the need for metaphysical creatures (a collection of his prose works is called The Necessary Angel). Yet somehow these poets are never mentioned in debates over religious truth. As the mythologist Joseph Campbell puts it, “we have people who consider themselves believers because they accept metaphors as facts, and we have others who classify themselves as atheists because they think religious metaphors are lies.”

What kind of metaphor are Rilke’s angels? At first, they sound like a Christian believer’s answer to modernity, and it’s true that Rilke was on a quest for an antidote to his anxious times. He sought out Russian spiritualism, the prophecies of Islam, the legacy of Orpheus, and various modes of aestheticism, but nothing satisfied him completely. (His notebooks remind one of Northrop Frye’s warning in Anatomy of Criticism: “The pursuit of beauty is much more dangerous nonsense than the pursuit of truth or goodness, because it affords a stronger temptation to the ego.”) In any case, Rilke’s angels aren’t reducible to those flitting through the Christian tradition. In 1921, he wrote in a letter that he was becoming anti-Christian—in fact, he was studying the Koran:

Surely the best alternative was Muhammad, breaking like a river through prehistoric mountains toward the one god with whom one may communicate so magnificently each morning without this telephone we call “Christ” into which people repeatedly call “Hello, who’s there?” although there is no answer.

Are Rilke’s angels Islamic, then? Maybe, but that’s obscuring the point. They seem instead to stand for a higher order of reality, and they offer Rilke a chance to imagine the world from beyond the ranks of humans. W. H. Auden saw this clearly: “While Shakespeare, for example, thought of the non-human world in terms of the human, Rilke thinks of the human in terms of the non-human, of what he calls Things (Dinge).” Language, of course, is a human thing we use to express the more-than-human. Metaphor is our only hope. As Stephen Mitchell puts it, Rilke’s angels are “embodied in the invisible elements of words.”

Physicists marvel at dark matter. Mathematicians are spellbound by imaginary numbers. Biologists delight in the intricate patterns of butterflies’ iridescent wings. Those who fall in love with poetry fall in love with metaphor. It dignifies our ignorance. It reminds us that the mind-body problem is something we can live with. Metaphor doesn’t explain the universe; it brings us closer to it. It revives our sense of this planet as a makeshift spiritual home, despite our need for clear religious or scientific interpretations. A metaphor, then, is like an angel—albeit one with limited power. Peter Cole, in The Invention of Influence, puts it succinctly:

Are angels evasions of actuality?

Bright denials of our mortality?

Or more like letters linking words

to worlds these heralds help us see?

Whatever visions he might have had, words are Rilke’s messengers. They travel lightly through time and space. They morph and shift as they travel. They will not visit our bedrooms at night “blazing like a star.” They may, however, reveal themselves as links to the world.