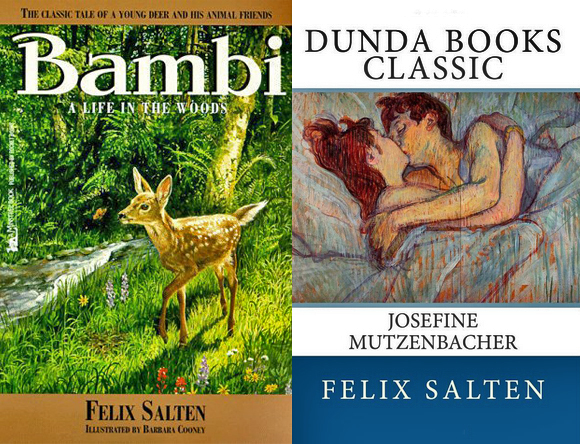

There is a trend in literary criticism these days—or perhaps I’m just noticing it for the first time—in which an essay opens with a discovery of a forgotten masterpiece. A writer finds on some dusty shelf on the third-and-a-half floor of the Strand the sequel to To Kill a Mockingbird, a volume of playful limericks by Simone Weil, or a collection of macabre fairy tales by Fran Lebowitz. I thought I was having one of these moments myself recently, when I stumbled across a book called The Memoirs of Josefine Mutzenbacher in my publisher’s office. The synopsis on the back of this edition, which looked like it was laminated and bound at a Staples, read: “Written by Felix Salten (Bambi), The Memoirs of Josefine Mutzenbacher is the story of a young girl and her many amorous encounters, with friends, family, and the local priest, culminating in her establishing a career as a high-priced courtesan.”

Bambi? Erotica? “The local priest”? I was beside myself at what I only assumed was my great fortune.

Before I dove into the book, however, I looked a bit into the history of Josefine, as it is often called. As it turns out, Josefine has a storied provenance. It was published anonymously—Salten never officially claimed authorship—in 1906, and caused an immediate stir amongst the rarefied circles of Vienna. Over the course of its lifetime, it has sold more than 3 million copies and been translated into at least ten languages, though little by way of critical writing about it can be found. The book has spawned parodies, pornos, plays, and even a few university courses.

In the 1960s, the Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons in Germany, charged with the placing of material inappropriate for youth under legally enforceable prohibition, first put Josefine on its list of “indexed” books. Another edition, released in 1978, was again added to the Index due to its lighthearted treatment of rape, incest, and prostitution. The prominent publishing house Rowohlt, responsible for German editions of acclaimed works by Henry Miller, Thomas Pynchon and Toni Morrison, among others, filed suit in the 1990s (it’s unclear why they had such a delayed reaction) at which point the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany ruled that the book must be removed from the Index, as pornography and art, they determined, were not mutually exclusive. Because the book is in the public domain, searching for it on Amazon will result in a number of editions from unheard-of publishing houses—the edition that I happened upon, which is riddled with typos and contains three pages of a completely unrelated text, was published by the Olympia Press, which also makes available such monuments to erotica as Adam and Two Eves, Carnal Prayer Mat, and The Temple of Pederasty, all available to download from their website. (The Press’ name is obviously a reference to the famous French press run by Maurice Girodias, best known for publishing Lolita and Naked Lunch.)

The story opens with an aging Josephine, or “Pepi,” as her affectionate molesters call her, reminiscing on how she saved herself from a life of “squalor and drudgery” by becoming a high-priced courtesan. Like a nymphomaniac version of St. Therese of Lisieux, Pepi feels upon her first consensual sexual encounter—an orgy with her older brother and two neighbor children—the stirrings of a higher calling. What follows is a detached narrative of a years-long sexual escapade that very rarely (I cannot stress this enough) breaks for descriptive prose or an emotional pronouncement. After the boarders in her parents’ home and the aforementioned brother and neighbors, she proceeds to pinch, fondle, suck, and be sucked by a beer merchant, her teacher, her priest and, the coup de grace, her father. The instigator isn’t always the dirty old man, though—Pepi is something of an erotic robot, offering herself up like a frosted cupcake to potential paramours both male and female, and, when she happens to be the prey, offering only the meekest of protestations, or, alternatively, a befuddlement so implausible that it’s impossible to read as sincere. When she goes to confession after a brief period of introspection, the priest tells her that simulating a carnal act with a man of God will ensure her salvation. When she looks back on this, she idiotically thinks, “I considered myself lucky to be able to have my sins forgiven.” If the above seems a sparing assessment of a literary phenomenon, it’s because the prose simply doesn’t warrant in-depth analysis, nor does it even register as titillating, because the concupiscent activity is so relentless that it becomes downright aggravating. In other words: if you don’t abstain between meals, you’ll never feel true hunger. The experience of reading it reminded me of a recent night out at a large, chichi nightclub in New York City. The DJ was quite possibly epileptic, as he would play a song for twenty seconds, scratch the record, and then move on to the next song. After about thirty minutes of this, a companion turned to me and deadpanned, “This man knows nothing about the female orgasm.”

Who was this Felix Salten? Was he actually ignorant of feminine pleasure and the art of subtlety? And how could that be, given that he was the talented and versatile author of a beloved classic that, in Disney-form at the very least, has been a formative piece of art for children for generations?

Salten was born Siegmund Salzmann in 1869 and grew up, like Pepi, in a Viennese slum. He was one of six children born to Jewish parents in a Vienna that was both a center of culture and a hotbed of anti-Semitic sentiment. As a young man, Salten toiled in insurance for a paycheck before he established himself as a writer with an impassioned obituary of Emile Zola upon the latter’s death in 1902. He quickly became a major figure in the Jung Wien (Young Vienna) movement, a conglomeration of sophisticated fin de siècle writers and cabaret artists, many of them Jewish, who met at cafes and attacked each other in their respective newspapers. Though Salten is not a household name––at least, on this side of the Atlantic––his literary canon is impressive. He wrote novellas, opera librettos, plays, art and theater criticism, Zionist speeches and pamphlets, and what can only be called the Victorian era equivalent of celebrity gossip. He was best known in the Viennese literary world as a feuilletonist, or a writer of blithe, superficial criticism, but, as the success, commercial and critical, of Bambi—the book is complex, frightening, and tender in a way that makes the Disney version look like Kundera-defined kitsch—and a few other works prove, he was also entirely capable of producing meaty, fervent writing when sufficiently compelled.

So why would a man who possessed such gifts stoop to such a torrid level? In 2006, David Rakoff published an essay in Tablet Magazine in which he theorized that Salten saw himself as a creature akin to Pepi: a focused individual who used hard work and natural gifts to escape from the horrors of the ghetto. Reading Beverly Driver Eddy’s meticulously researched biography Felix Salten: Man of Many Faces, one will find a lot of evidence that backs up and expands upon this theory. Eddy describes Salten as cagey, socially and professionally ambitious and quick to compartmentalize, a writer who was both dismissive of his opponents and yet professionally savvy enough to use a pseudonym when he suspected certain works would not be critically embraced. All his acquaintances, including his good friend Arthur Schnitzler, the other candidate suspected of penning Josefine, regularly decried him as two-faced and devoid of substance. (It’s also worth noting that he was a notorious spendthrift and would do anything for a buck, even put his literary reputation in jeopardy.) In the work in question, he fashioned a protagonist who, by virtue of her “success,” justifies the auteur’s own questionable characteristics. It is fitting that the heroine gets her start at such a tender age, too; much of Salten’s work communicates his reverence for the id by featuring animals and children romping happily through life before the cruel hand of society grasps hold. In Bambi, the world’s sadistic nature is emblemized by the local hunter, known only as “He.”

The most heart-wrenching moment is not the death of Bambi’s mother, which traumatized film-goers, but rather the death of a deer who was previously the hunter’s pet and who, after telling the other forest animals that the great Man would surely never hurt him, is shot at point-blank range by his former master. In Josefine, this exit from Eden comes when she begins to prostitute herself. When she turns on the red light, she begins to engage in more orchestrated sexual encounters (as opposed to the “innocent” games she played with the neighbor children) and becomes aware of the threat of syphilis, violent johns and arrest. In order to survive in the world, both Josefine and Bambi are forced to develop from balls of joyful naïveté into overly cold and self-reliant. Bambi follows his father’s advice and takes to a life roaming the woods alone, abandoning his lover and two young children. The Memoirs of Josefine Mutzenbacher closes with her apathetic summation of love: “He lies on top and she lives underneath, or vice versa. They do the pushing, and we are being pushed—that is the only difference. But life still goes on.” On the whole, theorizing that a being must harden one’s self to the world is a decidedly depressing vote for autarchy, but sadly, the world proved Salten right. Hitler banned all of his books in 1936 and, while Salten was luckier than many of his fellow Jews, he was finally forced out of Vienna—and the society he had strived so hard to join—in 1938, never to return to the pastoral Austrian countryside he so loved.

✖